history

Discover the Mystery Hotel Budapest, which once served as the beautiful home for the Freemasons of the Symbolic Grand Lodge.

Mystery Hotel Budapest, a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2021, dates back to 1896.

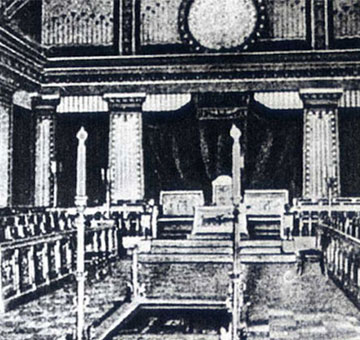

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2021, the Mystery Hotel Budapest is one of Hungary’s most exclusive holiday destinations. But this gorgeous location has not always been a luxurious historic hotel. Rather, it once served as the home for the Freemasons of the Symbolic Grand Lodge. On March 21, 1886, two different Freemasonry groups, The Freemasonry of the Order of John in Hungary and the Nagyoriens of Scottish rite, merged to create the first headquarters of the Symbolic Grand Lodge of Hungary. It quickly emerged as the center of the entire Hungarian Freemasonry movement, hosting hundreds of members from its headquarters in Budapest. By the end of the decade, it became clear to the group’s leadership that a much larger lodge was necessary. On February 27, 1890, the honorary and deputy grandmaster Antal Berecz and the general secretary Mór Gelléri formerly proposed the construction of a permanent lodge. It took three years to find the ideal location until finally, on May 1, 1893, Grand Master Ferenc Pulszky announced that the Grand Commission had purchased the plot at the corner of Podmaniczky and Vörösmarty streets. In October of that same year, a design competition was announced calling on applicants to submit their proposals for the Lodge. By February 1894, twelve proposals had been submitted from which the Grand Commission selected the designs of Ruppert Vilmos, who was himself a Freemason. Vilmos gradually developed a gorgeous towering edifice that extended several stories into the local skyline, emerging as one of the neighborhood’s most defining landmarks. The large Masonic temple on the fourth floor was the most impressive aspect of Ruppert’s work, serving as the focal point for the entire building’s design. On June 21, 1896, the new masonic lodge was completed and quickly became the epicenter of Hungarian Freemasonry.

From that time until 1919, the Hungarian Freemasonry flourished, collaborating with 11,000 Freemasons from hundreds of different lodges throughout the country. The building served as a field hospital during the First World War operated by the Grand Lodge. However, following the collapse of the greater Austro-Hungarian Empire after the First World War, the Hungarian Freemason movement went into decline. In 1920, the Republic of Councils in Hungary and the Interior Minister of Hungary, Mihály Dömötör, banned the activities of Freemasons. The Lodge was once again used as a military hospital during the Second World War, but would not be returned to the Freemasons until 1947. This, too, would be a short-lived occupation, as the Interior Ministry would quickly seize the building once again and would remain its primary custodians until the fall of the communist regime during the 1980s. Having acted as a government workplace for decades, the former Symbolic Grand Lodge headquarters finally saw new life as a boutique hotel in 2019. The building had changed considerably during its many different incarnations and its Freemasonry elements were concealed. Following a number of meticulous restorations guided by Hungarian interior designer Zoltán Varró, the building was brought back to life and transformed into the amazing “Mystery Hotel Budapest.” Varró masterfully recaptured the essence of the building’s Freemason past, incorporating elements of mystic and mystery to pay homage to this famous secret society. Few other destinations in the city can truly rival the majesty of the historic Mystery Hotel Budapest.

-

About the Location +

Like many other great European cities, Budapest can trace its lineage back to the time of the Roman Empire. The Romans first inhabited the region in the early 2nd century AD, building a frontier settlement known as “Aquincum” upon the site of an earlier Celtic town along the Danube. Today, the area is home to Budapest’s Óbuda neighborhood. At first, Aquincum’s sole purpose was to act as a military bastion for the Roman province of Pannonia Inferior. However, a small market town soon grew around the Roman base, gradually transforming the community into a regional hub of trade. Wealth subsequently flowed into Aquincum, giving rise to a construction boom that saw the creation of such renowned cultural structures like amphitheaters, villas, and public bathhouses. The Romans continued to occupy Aquincum for generations, until the collapse of their transcontinental empire in the 4th century. In the power vacuum that followed, roving bands of nomadic warriors—including the Huns and the Avars—sacked the city and dominated the surrounding plains for years. Political stability briefly returned to the locale when a joint army consisting of soldiers from both the Holy Roman Empire and Bulgaria defeated the marauders once and for all in the early 9th century. The Bulgarians subsequently claimed sovereignty over the land, developing two new fortified towns on opposite sides of the river called “Buda” and “Pest.”

The arrival of Arpad and his tribe of Magyars from Bulgaria at the end of the century eventually forced the local Bulgarians to leave Buda and Pest. Arpad and his descendants would subsequently rule over the two settlements for the next four centuries, using them both as the capital of the Principality of Hungary, and its successor, the Kingdom of Hungary. Buda and Pest remained economically vibrant throughout the Middle Ages, attracting all kinds of merchants from commerce-rich places like France, Wallonia (part of modern Belgium), and the Holy Roman Empire. Just like their Roman predecessor, the two towns were also military strongholds. The Bulgarians constantly warred with the Arpads in a series of related conflicts known as the “Bulgarian-Hungarian Wars,” while also withstanding the ferocity of the Mongols. Imposing embattlements eventually surrounded the two towns, making them some of the most heavily fortified communities in all of Europe. Buda itself started to emerge somewhat more prominently in Hungarian politics as a result, especially after King Béla IV placed his own royal palace (Buda Castle) atop the strategic high ground that sat at its center. As such, Buda had become the exclusive capital for the Kingdom of Hungary, as well as the home for successive generations of Hungarian monarchs.

The height of Buda and Pest’s prosperity within the Kingdom of Hungary occurred during the Renaissance, when King Matthias I sponsored the creation of many philosophical and scientific organizations including the Bibliotheca Corviniana, one of the most renowned libraries of the Renaissance world. However, the Kingdom of Hungary would eventually dissipate during Suleiman the Magnificent’s invasion of southeastern Europe in the 16th century. Now under Ottoman occupation, Buda and Pest reverted to being provincial capitals inside a much larger empire. Yet, the Ottomans invested heavily in the upkeep of both towns, sponsoring the creation of many outstanding facilities. Two of their greatest legacies are the Rudas Baths and the Király Baths, which are still in use today. The rule of the Ottomans proved to be comparatively brief, only lasting for some 150 years. In 1686, each city was recaptured by European forces amid the Great Turkish War. As such, Buda and Pest became a part of the Holy Roman Empire, before finally joining its successor—the Austrian Empire—two centuries later.

In 1848, an uprising of Hungarians throughout the Habsburg dominion nearly seized independence for Buda and Pest, but the Austrian imperial army was able to suppress the movement. The Austrian monarchs then proceeded to reestablish the Kingdom of Hungary as a form of reconciliation, joining its revived royal crown with that of Austria’s. Buda became the joint capital for the newly created Austro-Hungarian Empire alongside the city of Vienna. Pest joined its sibling community in 1873, when the two were merged into one single entity known as "Budapest." The local Hungarian government then initiated a massive series of renovations throughout the city, which resulted in the construction of such landmarks like Heroes' Square, Vajdahunyad Castle, and the many structures that reside along Andrássy Avenue. Budapest continued to function as the twin seat of power of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918, when it became the capital for an independent Hungary after World War I. Budapest has remained the center of government for Hungary ever since, even while it was occupied by the Nazis and Communists during the 20th century. Today, much of downtown Budapest is recognized for its grand historical significance, with much of its downtown core listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

-

About the Architecture +

When architect Ruppert Vilmos first designed the future Mystery Hotel Budapest, he selected the aesthetics of Classical Revival, Renaissance Revival, and Baroque Revival as the source for his inspiration. Vilmos specifically chose Classic Revival-style architecture for the building’s façade, while using a combination of Baroque and Renaissance Revival motifs throughout the interior. Also known as “Neoclassical,” Classic Revival architecture itself is among the most common architectural forms seen throughout the world today. This wonderful architectural style first became popular in Paris, specifically among French architectural students that studied in Rome in the late 18th century. Upon their return, the architects began emulating aspects of earlier Baroque design aesthetics into their designs, before finally settling on Greco-Roman examples. Over time, the embrace of Greco-Roman architectural themes spread across the world, reaching destinations like Germany, Spain, and Great Britain. As with the equally popular Revivalist styles of the same period, Classical Revival architect found an audience for its more formal nature. It specifically relied on stylistic design elements that incorporated such structural components, like the symmetrical placement of doors and windows, as well as a front porch crowned with a classical pediment.

Architects would also install a rounded front portico that possessed a balustraded flat roof. Pilasters and other sculptured ornamentations proliferated throughout the façade of the building as well. The most striking feature of buildings designed with Classical Revival-style architecture were massive columns that displayed some combination of Corinthian, Doric, or Ionic capitals. With its Greco-Roman temple-like form, Classical Revival-style architecture was considered most appropriate for municipal buildings like courthouses, libraries, and schools. Yet, the form found its way into more commercial uses over time, such as banks, department stores, and of course, hotels. Examples of the form can be found throughout many major cities, including London, Paris, and New York City. Architects still rely on Classic Revival architecture when designing new buildings or renovating historic ones, making it among the most ubiquitous architectural styles in the world.

On the other hand, Baroque Revival-style architecture, otherwise known as “Second Empire” style in France where it originated, was specifically meant for larger structures that could highlight the style’s ornate and grandiose architectural elements. Architects, business owners, and other professionals who embraced the form believed that it represented the best of modernity and human progress. This idea especially found an audience in America, where society was perceived to be on an upward path. In fact, the architecture had become so enmeshed in American society that some took to calling it “General Grant” style.

The form looked like the equally popular Italianate-style, which embraced an asymmetrical floor plan rooted to a “U” or “L” shaped foundation. These buildings usually stood at two to three stories, although some commercial structures—like hotels—exceeded that threshold. Large ornate windows proliferated across the facade, while a brilliant wrap-around porch occasionally functioned as the main entry point. The porches would also have several outstanding columns, designed to appear smooth in appearance. Every window and doorway featured decorative brackets that typically sat underneath lavish cornices and overhanging eaves. Gorgeous towers known as cupolas typically resided toward the top of the building.

However, Baroque-Revival architecture broke from Italianate in one major way—the appearance of the roof. Adherents to Baroque-Revival frequently incorporated a mansard-style roof, which consisted of a four-sided, gambrel-style structure that was divided among two different slopes. Set at a much longer, steeper angle than the first, the second slope often contained many beautiful dormer windows. The mansard roof became a principal component of the form following the construction of The Louvre which featured the design.

Finally, Renaissance Revival architecture—sometimes referred to as "Neo-Renaissance”—is a group of architecture revival styles that dates to the 19th century. Neither Grecian nor Gothic in appearance, Renaissance Revival-style architecture drew inspiration from a wide range of structural motifs found throughout Early Modern Western Europe. Architects in France and Italy were the first to embrace the artistic movement, viewing the architectural forms of the European Renaissance as an opportunity to reinvigorate a sense of civic pride throughout their communities. As such, those intellectuals incorporated the colonnades and low-pitched roofs of Renaissance-era buildings with the characteristics of Mannerist and Baroque-themed architecture. The greatest structural component to a Renaissance Revival-style building involved the installation of a grand staircase. This feature served as a central focal point for the design, often directing guests to a magnificent lobby or exterior courtyard.