Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the historic banana plants that reside within this famous agricultural estate that dates back to the late 1490s.

Hotel Hacienda de Abajo, a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2021, dates back to 1493.

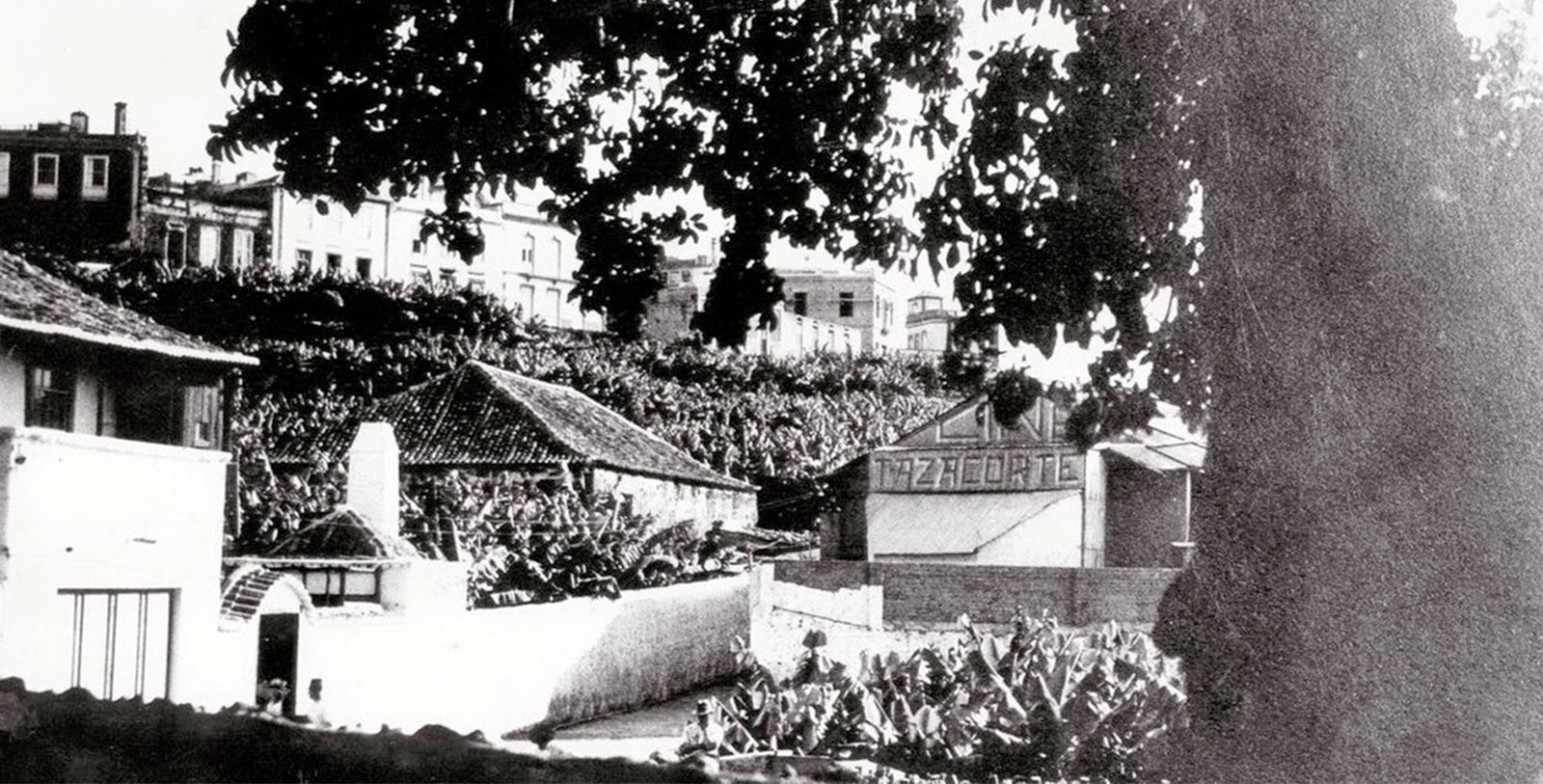

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2021, the Hotel Hacienda de Abajo is rich in both history and culture. This fabulous historic destination has resided within the Canaris Islands for centuries, specifically on the isle of La Palma. Castilian conquistadors under the direction of Alonso Fernández de Lugo first traveled to the area toward the end of the 15th century, establishing a small town called “Tazacorte” in 1493. Many of those adventurers created their own sprawling estates called “haciendas,” which functioned as self-sufficient homesteads that grew all kinds of commercial crops for sale in Europe. In fact, the conquistadors had settled the region due to the presence of fertile plains that existed nearby at the Aridane Valley and Tazacorte River. (The area’s proximity to the Tazacorte River also made it easier for the isolated colonists to remain in contact with the mainland, thus, making it a much more attractive place to settle.) Recent scholarship from Professor Jesús Pérez Morera has suggested that the Hacienda de Abajo was the first estate to debut in the locale, constructed by Alonso Fernández de Lugo’s nephew, Juan, only a few years after the arrival of the conquistadors. But Fernández did not possess the estate for long, as he eventually sold the plantation to the Wesler family in 1509. Wealthy bankers in the employ of Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire, the Weslers ultimately decided to sell the estate to their business partners Jacome de Monteverde, and his uncle, Johann Biess, for 8,000 gold florins. Monteverde and Biess subsequently became the most important landowners in all of La Palma, with the Hacienda de Abajo selling its sugarcane to countless merchants in Antwerp. Due to this activity, the Hacienda de Abajo received an extensive collection of European sculptures and paintings. (Guests can still view this amazing selection of artwork in the hacienda today!)

Monteverde eventually emerged as the sole owner of the Hacienda de Abajo, extending its boundaries for thousands of acres toward the shoreline. He also expanded upon the facilities within the estate, constructing a series of residential and commercial buildings anchored by a central square with a few regal mansions. A historic sugar mill also dominated the skyline, producing hundreds of pounds of sugarcane each year. (Unfortunately, the mill was disassembled in the 1840s.) Monteverde shifted the entrance out to the east and erected a huge terrace-viewpoint that commanded stunning views of both the sugarcane fields and the ocean. He also modified every interior inside the residential structures, decorating them with truly sumptuous, yet functional objects imported from Flanders and Andalusia. Over the following centuries, other buildings were constructed to house the members of prominent families who, by marriage or sale, had become part of the close-knit group of owners of the Hacienda de Abajo. Among the most influential to inhabit the estate after the Monteverde family was the House of Sotomayor Topete, whose members traced their linage to Ana de Monteverde. The Sotomayor Topete family featured some of the most powerful people to ever live in La Palma, including a former military governor of the island, Pedro de Sotomayor Topete y Monteverde. Pedro José de Sotomayor Topete Massieu Vandale also called the Hacienda de Abajo home for some time, constructing the Casa Principal of Tazacorte on the grounds during the 17th century. (The Casa Principal of Tazacorte would eventually debut as the main building of the hotel.) The Hacienda de Abajo is now a beautiful holiday destination that offers nothing but the best in contemporary comfort. Yet, despite its more recent identity as a brilliant vacation retreat, guests today can still feel the impressive historical ambiance that has defined the Hacienda de Abajo for more than seven centuries.

-

About the Location +

Despite their relative isolation off the coast of West Africa, La Palma and the rest of the Canary Islands have been known to people for thousands of years. For centuries, the island of La Palma had been inhabited by the Benahoritas, which European explorers later called the “Guanches.” Berber in origin, the Guanches were a primitive society possessing little more than Neolithic technology. They lived across La Palma in scattered settlements, based primarily out of the subterranean cave network that traversed the island. The Guanches managed to live in relative isolation, occasionally interacting with various adventurers from Europe and the Middle East who visited their island. In fact, anecdotal historical evidence suggests that a few ancient societies—including the Phoenicians and the Romans—traveled to La Palma while conducting limited expeditions of the mid-Atlantic. The famous Roman historian Pliny the Elder even wrote an extensive description of the greater Canary Islands, based on a series of accounts gathered from Juba II, Roman Governor of Mauretania (now modern-day Morocco). Yet, the first real investigation of the islands occurred in 1341, after a Genoese fleet under the leadership of Lancelot Malocello made landfall for the first time in decades. The Genoans subsequently conducted their own exhaustive study of La Palma, inspiring Portugal and Castille to compete for control over it during the 15th century. Castille—the precursor to modern Spain—eventually forced Portugal to concede its claims on the island following the Treaty of Alcáçovas, paving the way for widespread Spanish settlement starting in the late 1490s and early 1500s.

The first Spaniards to settle La Palma were Alonso Fernández de Lugo and his band of conquistadors. Fernández’s men quickly defeated the Guanches in 1493, although committed armed resistance continued for some time thereafter. Nevertheless, the Spanish crown continued to encourage the settlement of La Palma and the other Canary Islands over the course of the next several decades, using them as a springboard for voyages across the Atlantic to the “New World.” But merchants soon discovered that the archipelago was positioned perfectly in the northeasterly trade winds, allowing for massive fleets of commercial ships to efficiently travel to the newer Spanish settlements in Latin America and the Caribbean. (Most trips took four to six weeks, which was quick at the time.) The residents of the Canary Islands, thus, developed their own local economy that grew all kinds of staple crops for trade in both Spain and the Americas. Dozens of sprawling agricultural estates called “haciendas” debuted as such, as did various towns that facilitated the prosperous maritime commerce that dominated the islands. Cruz de La Palma soon became the most prominent port in all the Canary Islands, which ferried countless products to foreign markets in all over the world. Sugarcane was the most lucrative export shipped from La Palma, with most estates specializing in the crop. But Spanish American plantations evenutally surpassed those on the island in productivity, forcing its inhabitants to cultivate more refined goods like grapes, silk, and even dyes. (The grapes themselves were used to create a special type of dessert wine called “Malvasia” or “Malmsy.” It found a particularly enthusiastic market among the English, who imported hundreds of bottles annually.)

Local planters soon began growing another crop by the middle of the 1800s—bananas. La Palma’s economic shift reflected new trends that had affected the larger Spanish world, specifically the dissolution of Spain’s American Empire at the start of the century. Increased global competition greatly destabilized the economy, incentivizing the farmers to seek new, innovates ways to earn a living. As such, they turned to the cultivation of bananas, which found a hospitable environment on La Palma. The banana plant had long enjoyed the tropical climate of La Palma, with the first trees arriving at the Hacienda de Abajo around the start of the 17th century. (The descendants of those first trees still exist at the hotel today, residing in its walled garden.) But with other areas of the local economy under much duress, planters throughout La Palma decided to create their own banana orchards. Soon enough, seemingly endless acres of banana farmland spread throughout the island. The industry subsequently thrived in La Palma, constituting one of the main local trades that its inhabitants adopted for generations to come. By the middle of the 20th century, the cultivation of bananas had comprised nearly 80% of the local economy! Today, La Palma continues to be an international leader in the distribution of raw bananas. Yet, it has also emerged as one of the globe’s most popular vacation retreats, enchanting throngs of guests each year with its crystalline waters and tranquil beaches. Many of its impressive landmarks also allure innumerable visitors year after year, such as the Parque Nacional de la Caldera de Taburiente (Caldera de Taburiente National Park), the Roque de Los Muchachos, and downtown Santa Cruz de la Palma.

-

About the Architecture +

Celebrated architect María del Carmen Alemañ García meticulously began renovating the historic Hotel Hacienda de Abajo in 2010. The project lasted for two years and focused on completely rehabilitating the facility’s main building, once known as the “Casa Principal of Tazacorte.” She specifically removed some more contemporary architectural additions, while also recovering the original appearance of the house. The Casa Principal of Tazacorte itself debuted back during the 17th century when Pedro José de Sotomayor Topete Massieu Vandale first commissioned to have it constructed. The Casa Principal of Tazacorte subsequently featured an eclectic mixture of Spanish Colonial architecture, displaying typical structural elements like thick, stucco walls, a central courtyard, and a Moorish-inspired tile roof. Vandale also oversaw the development of numerous balconies that overlooked the sugarcane fields, as well as two gorgeous towers that were very “militaristic” in their appearance. Yet, the structure contained unique aspects of Canarian design aesthetics, too, with the main rectangular layout forming various wings that resembled either an “L” or “U” shape. Most of the architectural features fulfilled a pragmatic role just as much as a decorative one. For instance, the home contained a massive stove that its tenants could use of drying cochineal for the production of dye—one of the hacienda’s staple crops several centuries ago.

Also scattered throughout the grounds are several additional buildings, developed recently to restore the original look and feel of the historic hacienda. As such, they respect the estate’s original layout and construction style, showcasing the same colonial architecture that still defines the main building today. One of them is a two-floor building with Moorish-style tiled roofs and open balconies, while the other two are single-story structures that bare similar characteristics. Of those two latter buildings, one currently houses a replica of a historic chapel that once resided within the Hacienda de Abajo. The other structure contains a brilliant bathhouse that is full of rich architectural details. The doors, windows, and other elements used for both the exterior and interior of the buildings were all constructed from buildings that once stood on La Palma from 17th to the 19th centuries. This practice reflects a very common exercise in Canarian architecture: the reuse of wood, ashlars, and stones from demolished structures for use in new buildings.

The Hotel Hacienda de Abajo’s architecture is complimented by a series of fascinating antiques that its previous tenants acquired over hundreds of years. More than 1,300 works of art adorn the hacienda, with some dating back to the 16th century. Together, they represent one of the most significant collections of art in all of La Palma. In fact, the Hotel Hacienda de Abajo boasts the best collection of tapestries in the Canary Islands, (specifically French and Flemish pieces from the 16th to the 18th centuries); a valuable art gallery with works from the 15th to the 20th centuries; European furniture from the 17th to the 19th centuries; delicate religious carvings from the 16th to the 19th centuries; and a whole host of other historical artifacts. Past owners acquired nearly every object through exchanges based in the major European cities that distributed the estate’s sugarcane and banana crops, such as Seville and Antwerp. But the galleons of the Spanish Treasure Fleet introduced many additional kinds of rare items from Asia, including the hacienda’s amazing collection of Chinese sculptures, furniture, and porcelain that date from the Tang Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty. All this makes the hotel a hallmark of the Canarian art scene, where every corner of the hotel features a delightful surprise for art lovers.

Another unique architectural feature is actually the hotel’s garden, once the former banana orchard that the Sotomayor Topete family originally established in 1613. (The patriarch of the family at the time—Pedro de Sotomayor Topete y Monteverde—acquired the bananas from abroad as a means of supplementing the hacienda’s sugarcane trade. They subsequently became the first bananas ever grown on La Palma.) The gardens are now the centerpiece to the Hotel Hacienda de Abajo’s magnificent landscape, featuring many species of exotic plants from all over the world, such as the African mainland and the Americas. But there are also many unique types of native Canarian plants inside the garden, too, offering to guests the opportunity to experience the inherent beauty of the Canary Islands firsthand. Water from local springs and creeks inside the Parque Nacional de la Caldera de Taburiente keep the garden healthy, arriving by way of an irrigation network that makes use of ancient aqueducts. The space itself is divided into two asymmetrical areas of ornamental parterres that contain pergolas, fountains, a pond, and even a swimming pool. Guests can even explore the remains of a historic sugarcane mill that once operated at the hacienda centuries ago.