Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Westin Poinsett, which has been offering exceptional service as a Greenville standby since 1925.

The Westin Poinsett, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2002, dates back to 1925.

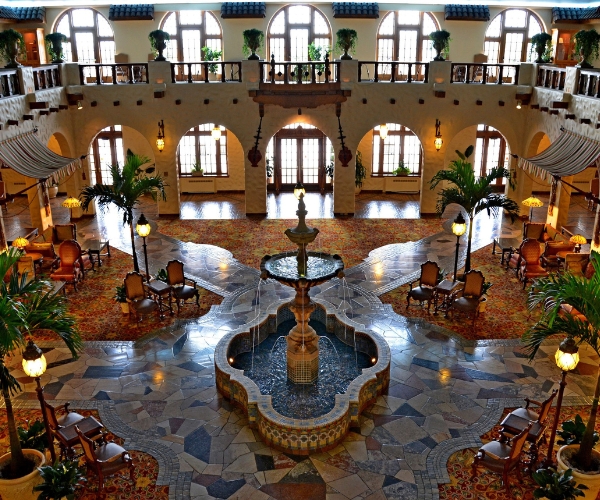

VIEW TIMELINESouth Main Street in Greenville, South Carolina, was once home to the Mansion House Hotel for over a century until it was torn down in 1924. The following year, the Poinsett Hotel was constructed just a few feet from the former site of Mansion House Hotel. To complete the project, the hotel’s ownership group hired the renowned William Lee Stoddard as their lead architect. Stoddard had developed a considerable reputation by that point, having designed countless awe-inspiring destinations across the United States. Stoddart subsequently created a gorgeous 12-story structure that featured some of the best Beaux-Arts-inspired architecture throughout the entire state. The building itself sat upon an L-shaped foundation with the first four stories serving as the base of the design. Perhaps the most defining feature Stoddart installed within this section was the tall arched windows that covered the span of the second and third levels. A wide cornice then separated the based from the “shaft,” which extended for an additional seven stories. The final floor featured an ornate capital cornice, as well as a stunning balustraded parapet. Beautiful architectural details proliferated throughout the exterior, too, ranging from terra cotta festoons to rich modillion blocks. Inside, Stoddart created a lounge, a grill room, and a convention hall, as well as 210 stunning amazing accommodations. Each guestroom had the most cutting-edge amenities to date, including private baths outfitted with luxurious fixtures. Stoddart even set aside space for nearly a dozen shops to open on the ground floor! Ultimately, it took several months and $1.5 million to create the structure. The brand-new hotel was well received across Greenville when construction finally concluded in the spring of 1925. The owners eventually decided to name the business as “The Poinsett” in honor of Joel R. Poinsett, a prominent South Carolina politician who had once served as the Secretary of War under former President Martin Van Buren.

But despite its acclaimed design, the hotel surprisingly did not make a profit during its first years of operation. To reverse The Poinsett’s fortunes, ownership hired J. Mason Alexander to serve as general manager. Known as “Old Admiral Spit and Polish,” Alexander was reputed throughout the hotel industry for his unique approach to hospitality. He specifically embraced a strategy that he deemed “The Four C’s,” which stood for cleanliness, cooking, competence, and courtesy. True to his reputation, Alexander managed to dramatically revitalize the hotel in just a matter of years. By 1940, Alexander’s stewardship had many calling The Poinsett, “Carolina’s Finest.” The hotel’s meeting spaces were constantly filled for family dinners and formal dances, while the guestrooms were nearly booked to capacity each night. A huge reason why The Poinsett’s popularity soared was Alexander’s close attention to detail. In fact, he conducted the hotel’s maintenance as if he was caring for his own home. Guests were also allured by the numerous, innovative marketing programs that Alexander ran for the business. One of the most peculiar—and iconic—was his “clean money” policy. Alexander specifically had his staff wash the coins in the registers, ensuring that each patron touched spotless currency whenever they checked in or out. Due to its success, Alexander had to supervise a massive expansion to the building shortly before America’s entrance into World War II. The work developed various new amenities within the hotel, along with 60 more guestrooms! Thanks to J. Mason Alexander’s great care, countless guests from all over American continued to flock to The Poinsett. Indeed, some of the country’s most prolific figures visited on occasion, including Amelia Earhart, John Barrymore, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Senator Bobby Kennedy, and Liberace.

During the mid-1950s, the local motel industry boomed at the expense of many neighboring city-center hotels. Following this shift within the hospitality industry, The Poinsett was sold to the Jack Tarr Hotel in 1959. The hotel nonetheless lost money yet again, even as the Jack Tarr Hotels thoroughly tried to renovate the structure over the following decade. It then changed ownership numerous times throughout the 1970s and 1980s, with one owner even operating the building as a retirement home for a few years. Left vacant shortly thereafter, The Poinsett Hotel was subsequently considered one of the eleven most endangered historical sites in all of South Carolina. It remained empty until November 1997, when P. Steven Dopp and Greg Lenox—already the owners of the historic Francis Marion Hotel—purchased the site and began an extensive renovation process. After three years of extensive construction, the owners, former employees, and friends of the revitalized hotel celebrated its grand debut on the 75th anniversary of its original opening. In fact, the festivities involved a special exhibit in city hall, as well as a magnificent reception in the restored Gold Ballroom. “The Westin Poinsett” itself officially reopened on October 22, 2000. Since then, The Westin Poinsett has regained its reputation as one of South Carolina’s finest hotels. With its lavish arrangements and thoughtfully appointed furnishings, the hotel lends the treasured ambiance of its historic beginnings. A member of Historic Hotels of America since 2002, this fantastic historic hotel continues to be among the most fascinating holiday destinations throughout the American South.

-

About the Location +

Located in South Carolina’s Upstate region, Greenville’s origins harken back to a plantation operated by Richard Pearis during the early 1770s. An Indian trader from Virginia, Pearis had been granted the tract of land from a local Cherokee chieftain who was also father-in-law. He specifically settled some 100,000 acres, with his actual estate, “Great Plains,” situated along the Reedy River. Pearis gradually developed an agricultural complex on the site, building multiple structures that included a few mills and a trading post. But the American Revolution erupted shortly thereafter, greatly disrupting the prosperity of Pearis’ farm. He subsequently sided with the Loyalists, although the decision cost him dearly. Local Patriot militiamen eventually located Pearis’ plantation and torched it to the ground in retribution. They even managed to capture Pearis, whom they jailed briefly in the colonial capital of Charleston. Pearis never returned to the home, leaving his erstwhile estate as the property of the new South Carolina state government. It subsequently partitioned the land to war veterans in honor of the service in the Continental Army. Among the first to settle the area was Thomas Brandon. Purchasing some 400 acres of Pearis’ former plantation, he lived on the land for the next several years until another speculator named Lemuel Alston bought it for himself. Alston thoroughly encouraged the area’s development, even sponsoring the creation of a small village he called “Pleasantbury.” Founded upon the actual site of Pearis’ farm, it consisted of a few dozen log cabins centered around a public square. Over time, the residents adopted the new moniker of “Greenville Courthouse”—and then just “Greenville”—in order to denote the presence of the local county courthouse. (Many scholars speculate that Greenville County as a whole was named after General Nathanael Greene, a great war Revolutionary War hero.)

Greenville’s growth continued into the 19th century, especially once Vardy McBee became the primary landlord. While McBee never lived in the region, he understood that a prosperous Greenville would provide a healthy return on his investment. As such, he donated land for the creation of many municipal buildings, like churches, schools, and public meeting houses. McBee also encouraged the emergence of industry nearby, too, which resulted in the debut of tanneries, mills, and factories. McBee even helped establish a prestigious college in town known as “Furman University.” A small yet vibrant tourism economy materialized as well, fueled by the arrival of the Greenville and Columbia Railroad during the 1850s. In fact, the arrival of those travelers inspired some local business leaders to open a hostelry called the “Manson House Hotel” in downtown Greenville. Thanks to McBee’s patronage, many across South Carolina had actually begun to refer to it as the “Athens of the Upstate.” Greenville remained an important cultural and economic center, even as the rest of South Carolina was in ruins in the wake of the American Civil War. Construction on new commercial enterprises flourished, specifically the creation of many cotton mills just outside of town. Wealth quickly flowed into Greenville unlike ever before, elevating it to the status of a city around the 1870s. The community’s prosperity endured for many years thereafter, too, save for a brief period where the Great Depression caused its factories and mills to temporarily shut down. Today, Greenville has since maintained its prestigious status throughout South Carolina. It also continues to entertain a robust tourism industry that cultural heritage travelers today will find to be very exciting. For instance, Greenville is home to many outstanding attractions, including the Upcountry History Museum, The Peace Center, and Falls Park on the Reedy. Come experience this wonderful Southern city firsthand now!

-

About the Architecture +

To construct a brilliant new hotel called “The Poinsett,” several local business leaders hired the renowned William Lee Stoddard to spearhead the project. Stoddard had built a considerable reputation by that point, having designed countless awe-inspiring structures across the United States. Stoddart subsequently created a gorgeous 12-story structure that featured some of the best architectural motifs throughout the entire Palmetto State. The building itself sat upon an L-shaped foundation with the first four stories serving as the base for the design. Perhaps the most defining feature Stoddart installed within this section of the hotel was the tall arched windows that covered the span of the second and third levels. A wide cornice then separated the based from the “shaft,” which extended for an additional seven stories. The final floor featured an ornate capital cornice, as well as a stunning balustraded parapet. Beautiful architectural details proliferated throughout the exterior, too, ranging from terra cotta festoons to rich modillion blocks. Inside, Stoddart created a lounge, a grill room, and a convention hall, as well as 210 amazing accommodations. Each guestroom had the most cutting-edge amenities to date, including private baths outfitted with the best fixtures. Stoddart even set aside space for nearly a dozen shops!

Stoddard also used a wonderful blend of Beaux-Arts style architecture as the source of his inspiration, which became widely popular around the dawn of the 20th century. This beautiful architectural form originally began at an art school in Paris known as the École des Beaux-Arts during the 1830s. There was much resistance to the Neoclassism of the day among French artists, who yearned for the intellectual freedom to pursue less rigid design aesthetics. Four instructors in particular were responsible for establishing the movement: Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste, and Léon Vaudoyer. The training that these instructors created involved fusing architectural elements from several earlier styles, including Imperial Roman, Italian Renaissance, ad Baroque. As such, a typical building created with Beaux-Arts-inspired designs would feature a rusticated first story, followed by several more simplistic ones. A flat roof would then top the structure. Symmetry became the defining character, with every building’s layout featuring such elements like balustrades, pilasters, and cartouches. Sculptures and other carvings were commonplace throughout the design, too. Beaux-Arts only found a receptive audience in France and the United States though, as most other Western architects at the time gravitated toward British design principles.