Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

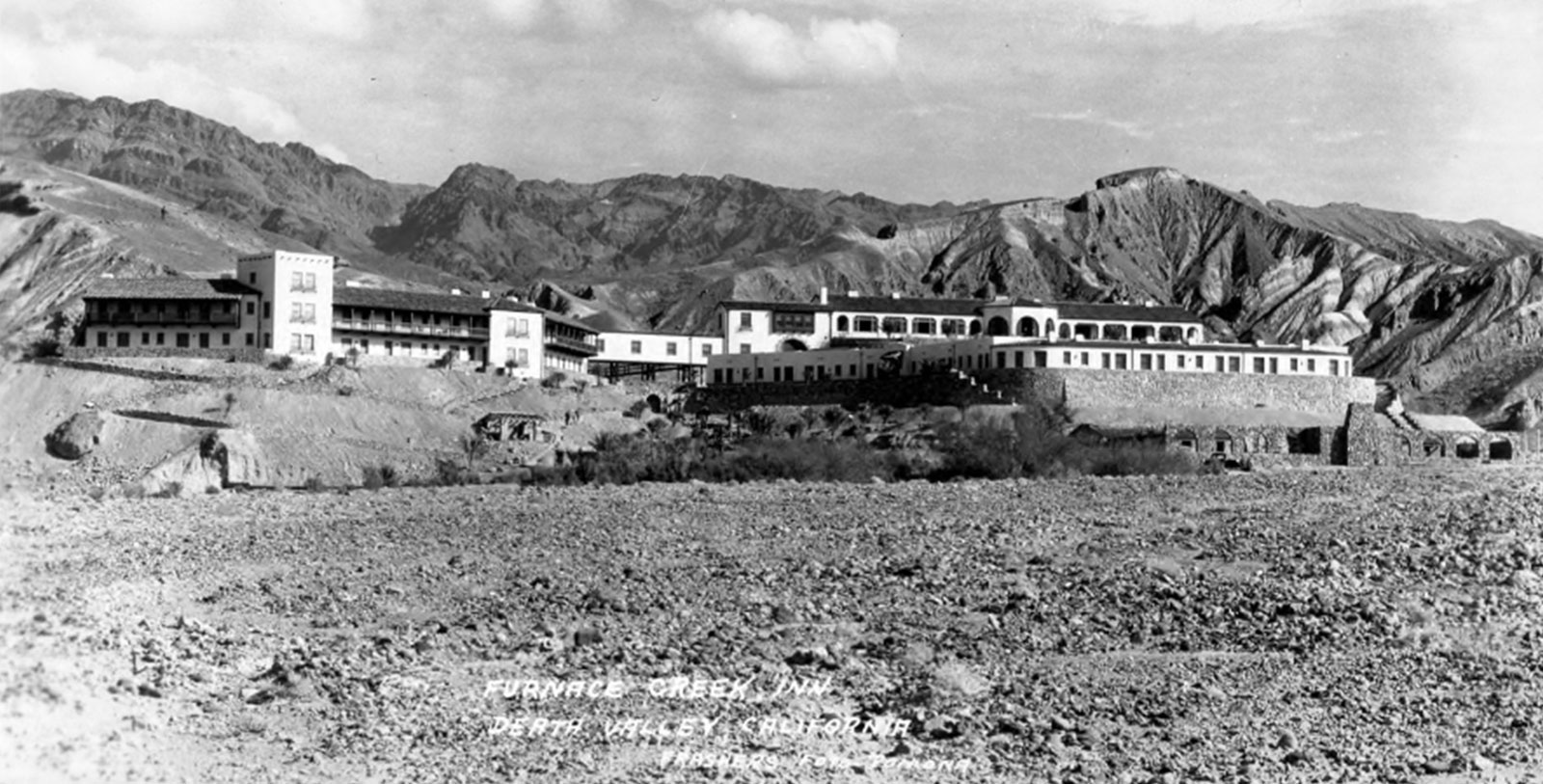

Discover the Inn at Death Valley, which was originally constructed as the Furnace Creek Inn.

The Inn at Death Valley, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 1999, dates back to 1926.

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels of America since 1999, The Inn at Death Valley has been one of the California’s best retreats. This spectacular resort is also among the most historic in the state, as it has been in continuous operations for almost a century. Its origins specifically harken back to the prominent Pacific Coast Borax Company and its now-famous activities in the heart of Death Valley. Despite the region’s inhospitable climate, the business nonetheless made a significant fortune mining borate in the area. Starting in the 1890s, it had continuously hauled large quantities across the desert landscape via two interconnected railways—the Death Valley Railroad and the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad. The massive surplus even inspired the business to manufacture its own cleaning solvent called “20 Mule Team Borax,” which rose to become very popular in the United States. As such, the Pacific Coast Borax Company had created a considerable economic empire that loomed over all the other regional mines. But the company’s corporate leadership eventually realized that the demand for its borate would not last forever. Seeking to diversify its portfolio, the Pacific Coast Borax Company ultimately turned to tourism. It was convinced that Death Valley could evolve into a lucrative holiday destination due to the region’s countless natural attractions.

The Pacific Coast Borax Company began investigating potential sites amid its greater push to make Death Valley a national park during the 1920s. At first, the Pacific Coast Borax Company settled on using a preexisting ranch near a place called “Furnace Creek,” although the plans were later abandoned when it was considered too isolated. Instead, the corporation settled on constructing its own facility just a few miles away at the mouth of the creek bed. A team consisting of architect Albert C. Martin and landscaper Daniel Hull then arrived on-site and began crafting a brilliant compound that dominated the local skyline. The entire project was incredibly comprehensive, taking months to complete. But when the construction finally concluded in 1927, the new “Furnace Creek Inn” stood as an engineering masterpiece. Both Martin and Hall had brilliantly crafted the resort’s appearance to resemble the kind of historic mission complexes that once proliferated across California. For the building itself, Martin had applied many unique architectural features—like stucco walls, open arcades, and red tile roofing—that truly evoked the state’s Spanish heritage. Meanwhile, Hall had laid down an intricate layout of plants that made the resort appear as if it had materialized out of a dream.

The Furnace Creek Inn’s design was immediately well-received, much to the excitement of the Pacific Coast Borax Company. Tourists began reserving accommodations in droves, prompting the business to further expand upon its available facilities. It also ran promotional sightseeing bus tours that ferried its guests from the resort to places all over Death Valley. Despite the resort’s stunning success, the Pacific Coast Borax Company had to sell it just a few years later. Unfortunately, financial troubles were already starting to affect the company. Not only was it expensive to fuel the whole resort, but it cost a significant amount to bring food and workers into the desert. Ironically, the greatest obstacle to affect the company’s finances was the National Park Service. During the 1930s, the agency had paved all the local roads following the creation of Death Valley National Monument in 1933. The use of the Pacific Coast Borax Company’s passenger trains collapsed, which effectively destroyed one half of its entire business model. In the end, the Pacific Coast Borax Company was forced to sell the resort to new owners.

Nevertheless, the Furnace Creek Inn continued to be an immensely popular resort for generations to come. Many high-profile celebrities—such as Bette Davis, John Wayne, and Marlon Brandon—requested guestrooms, too, especially once Hollywood executives began making films in Death Valley. (In fact, a few directors even shot scenes of their movies at the resort itself, such as The Lively Set and Winter Kills.) Some actresses and actors also decided to arrive on their own. Indeed, Clark Gable and Carol Lombard spent a portion of their honeymoon in the resort, while Anthony Quinn often brought his family out for long vacations. Ronald Reagan was even a guest long before his ascent into American politics. Although not as famous as his fellow colleagues at the time, the actor nonetheless visited for a full week back during the 1940s! The resort’s storied reputation only grew stronger after the Xanterra Travel Collection acquired the destination in 1968. Xanterra invested heavily into its preservation, initiating a few massive renovations over the next four decades. Perhaps the largest to transpire concluded in 2018, when the resort was reborn as “The Inn at Death Valley” and integrated into a luxurious complex called the “Oasis at Death Valley.” Still under the stewardship of Xanterra Travel Collection, the future of this fantastic historic resort has never looked brighter.

-

About the Location +

For thousands of years, various tribes of Native Americans lived in today’s Death Valley National Park. The earliest indigenous people left little evidence behind of their presence, save for unique petroglyphs scattered about on various local rock formations. The Timbisha eventually moved into the region and established some of the first enduring permanent settlements in Death Valley. Due to the dramatic seasonal change in temperature, the Timbisha followed periodic migration habits that saw them temporarily relocate into the mountains during the summer months. Nevertheless, the valley remained sparsely populated, even as American settlers began pushing toward the Pacific Coast throughout most of the 1800s. Those pioneers actively avoided the area following the highly publicized ordeal of the Bennett-Arcane Party wagon train. Part of a much large convoy of families heading west amid the California Gold Rush, the members of the Bennett-Arcane Party became convinced of a supposed short-cut through the valley. Unfortunately, the tip proved to be an exaggeration. The Bennett-Arcane Party ultimately spent four months stumbling around the area, losing many of their wagons and oxen along the way. When the group finally left, one of its members uttered, “Goodbye, Death Valley.” The line spread quickly and cemented the valley’s status as an incredibly inhospitable place within America’s collective imagination.

Nevertheless, a few enterprising individuals eventually settled in Death Valley upon learning of its rich mineral deposits. Several dozen mines soon opened up next to lodes of gold and cooper, as well as numerous evaporates. But the most prosperous mining operations excavated borate, an ingredient used in many cleaning solvents during both the 19th and 20th centuries. The first borate mines opened under the direction of Eagle Borax Works in 1881, although it soon had to contend with several competitors just a few years later. The greatest of those newer corporations was the Pacific Coast Borax Company, established by Francis Marion Smith in 1890. Smith and his Pacific Coat Borax Company ran most of their mines around a series of borate deposits that resided below the surface of Furnace Creek. Luckily for Smith, the layer proved to be incredibly rich in borate. Soon enough, the company was transporting pounds of borate every day. The sheer amount even prompted Smith to operate his own freight trains, called the “Death Valley Railroad” and the “Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad.” (The Tonopah & Tidewater itself extended for hundreds of miles all over southern California and even into parts of Nevada.)

Over time, the members of the Pacific Coast Borax Company grew concerned over the fate of its borate mining operations. The company then shifted toward promoting tourism into Death Valley, convinced that contemporary Americans would come to appreciate its beautiful scenery—especially if they had a wonderful place to stay. The Pacific Coast Borax Company thus began constructing the Furnace Creek Inn near the grounds of its former mines during the mid-1920s. It also engaged in an energetic marketing campaign that sought to dispel the reigning myths of Death Valley. But the advertising carried another goal that the Pacific Coast Borax Company hoped to achieve. Genuinely concerned about the valley’s conservation, the business wanted to have it protected as a U.S. National Park. Working alongside the head of the National Park Service, the Pacific Coast Borax Company succeeded in changing the commonly held views of Death Valley. The campaign even produced numerous grassroot movements that spurred the federal government to finally make Death Valley a national monument in 1933.

Elevated to an official national park in 1994, countless people have traveled out to Death Valley over the years. Indeed, the park’s unique tranquility and scenery have even inspired Hollywood directors to shoot their films on-site. (The long list to movies to use Death Valley as a cinematic backdrop include such titles like The Bridge Came C.O.D., 3 Godfathers, One-Eyed Jacks, and parts of George Lucas’ Star Wars franchise.) Among the most enduring popular attractions within Death Valley have been Zabriskie Point, the Badwater Basin, and the Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes. Guests were also amazed by the sailing stones of Racetrack Playa, which glide across the desert sand seemingly on their own! Manmade structures have allured many travelers, too, most notably a palatial manor known as “Scotty’s Castle.” Built gradually over the 1920s and early 1930s, Scotty’s Castle was once the summer retreat for a Chicago-based insurance tycoon named Albert Mussey Johnson. Johnson had first learned of Death Valley from a con artist named Walter Scott, who had erroneously convinced him to invest in mines throughout the area. Despite the earlier nature of their relationship, the two became best friends. The name “Scotty’s Castle” was an homage to Scott himself, which the two pretended to live inside as part of a joke that they would play on unsuspecting guests.

-

About the Architecture +

The Inn at Death Valley stands today as a brilliant example of California Mission Revival. An offshoot of the larger Spanish Colonial Revival-style, California Mission Revival first emerged in the United States during Gilded Age. The movement specifically enjoyed its greatest popularity from 1890 to 1915, although it continued to be used by architects well into the late 20th century. The California Mission Revival style of architecture—and subsequent Spanish Colonial Revival style—have a historical and cultural predominance in the southwestern United States, as it is a common sight throughout that region of the country. Franciscan monasteries constructed throughout California during the 1700s served as the primary source of inspiration for California Mission Revival-style architecture. In a manner reminiscent to those monasteries, buildings developed with California Mission Revival architecture embraced design principles that focused on necessity and security. As such, California Mission Revival-themed blueprints featured structures centered around an enclosed courtyard with massive adobe walls. The walls themselves had broad, unadorned stucco surfaces that contained limited fenestration, red clay tiling, and low-pitched roofing. Other prominent structural components to California Mission Revival-style buildings included an enfilade of interior spaces, semi-independent bell-gables, and curved “Baroque” gables installed on the primary façade. Many of these architectural components can still be seen throughout the Inn at Death Valley today, such as its stucco walls, open archways, and red tile roofing.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Marlon Brando, actor known for his roles in films like The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, and A Streetcar Named Desire.

Clark Gable, actor known for his roles in films like It Happened One Night, Mutiny on the Bounty, Gone with the Wind.

Carol Lombard, actress known for her roles in films like My Man Godfrey, Nothing Sacred, and To Be or Not to Be.

Bette Davis, actress known for her roles in films like All About Eve, Jezebel, and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

John Wayne, actor known for his roles in films like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, True Grit, and The Longest Day.

Jimmy Stewart, actor known for his roles in films like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The Man Who Shot Liberty Vance, and It’s a Wonderful Life.

Anthony Quinn, actor known for his roles in films like Zorba the Greek, The Guns of Navarone, and La Strada.

James Cagney, actor known for his roles in films like Angels with Dirty Faces, White Heat, and Yankee Doodle Dandy.

John Ford, director known for filming movies like Stagecoach, Searchers, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Ernest Hemingway, author known for writing such books like A Farwell to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea.

Laura Bush, First Lady of former U.S. President George W. Bush (2001 – 2009)

Ronald Reagan, 40th President of the United States (1981 – 1989)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

The Lively Set (1964)

Winter Kills (1979)

Valley of Love (2015)