Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

historic hotel in boston

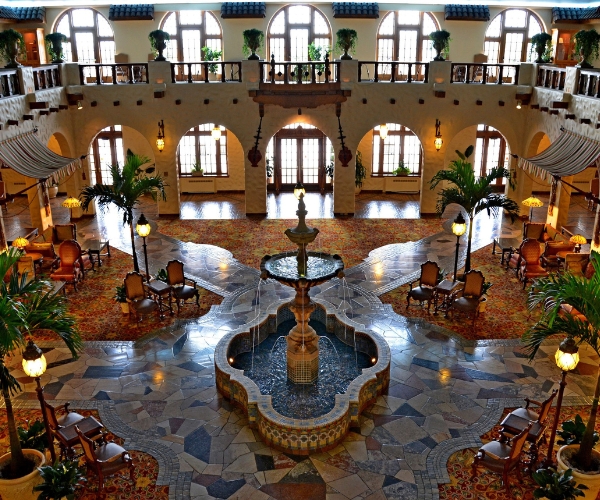

Discover The Eliot Hotel, which has been one of the best places to stay in Boston’s prestigious Back Bay neighborhood for nearly a century.

The Eliot Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2024, dates back to 1925.

VIEW TIMELINEBy the height of the Roaring Twenties, the quaint Bostonian neighborhood known as the “Back Bay” had become one of the finest locations in the entire city. Municipal architects had spent years painstakingly reconstructing the area to imitate the iconic designs of renowned 19th-century French engineer Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Grand Parisian-inspired avenues ran across Back Bay, which were lined by rows of brownstone townhouses styled like Haussmann’s distinctive architectural approach. Over time, Back Bay’s revitalized appearance made it an enticing place to visit, particularly for the many intellectuals invited to work at the educational institutions nearby. A few enterprising entrepreneurs thus began creating dozens of extravagant hotels across Back Bay, hoping their impressive character would attract the business of those traveling scholars. Among the ambitious group of people seeking to capitalize on the situation was former Harvard University president Charles William Eliot and his family. Recognizing the economic potential of Back Bay, the Eliots specifically sought to create a hotel for the exclusive use of Harvard University’s guest lecturers. That vision soon became reality, and today, The Eliot stands as a historic hotel Boston visitors admire for its timeless elegance and charm. To that end, Eliot and his family subsequently bought an undeveloped plot of land next to the Harvard University alumni club during the mid-1920s."

They then established a lucrative partnership with architect Harold Field Kellogg in 1925, who in turn started designing a gorgeous nine-story apartment hotel that loomed majestically over Back Bay’s picturesque skyline. (Interestingly, Kellogg chose to use Georgian Revival style architecture as the main source of his inspiration, although he did incorporate some of the area’s larger French influences into the design, too.) But while Eliot did not live to see the project finished, the new “Eliot Hotel” nonetheless proved to be very popular with Harvard University’s visiting academics upon its debut a year later. The Eliot Hotel quickly flourished under the guidance of the Eliot family, who implemented a level of excellent service that was nearly unrivaled in the area. Their masterful management even caused some of the school’s retired professors to reserve guestroom apartments on-site for months at a time. Unfortunately for the Eliots though, the economic malaise spawned by the Great Depression eventually forced them into bankruptcy. Facing no other alternative, the family ultimately decided to sell the structure to new owners. The Eliot Hotel then passed through various proprietors until Nathan Ullian and his business partners acquired the site shortly before World War II. Sparing no expense, the group thoroughly renovated the building to revitalize its intriguing character.

Brilliant upscale amenities returned to the guestrooms in great quantities, as did a host of outstanding linens and décor. The revitalized hotel soon began to thrive yet again, reemerging as the choice venue for Harvard University’s respected faculty. Much of this success was thanks to Ullian’s wise decision to open The Eliot Hotel to more than just the Harvard University community. Indeed, the building soon became one of Back Bay’s more frequented social gathering spots by the middle of the century, having come to host countless guests from numerous backgrounds. Perhaps the finest attraction that The Eliot Hotel offered then was the affiliated Eliot Lounge, which was crowded every night due to its stunning cuisine and thrilling entertainment. Nevertheless, The Eliot Hotel has since remained a revered holiday destination, continuing to accommodate thousands of enthusiastic travelers each year. Much of its success has been thanks to the dedicated efforts of Dorian Ullian—daughter-in-law of Nathan Ullian—whose family has diligently looked after the hotel’s fantastic legacy for 85 years. (The Ullian family has also received irreplaceable help from longstanding general manager Pascale Schlaefli, who has been with The Eliot Hotel for more than 25 years.) In fact, the Ullians will celebrate the centennial anniversary of The Eliot Hotel in 2025—an extraordinary accomplishment for both the family and the business.

-

About the Location +

While Back Bay is a celebrated holiday destination today, it also has a fascinating history as one of the country’s most impressive infrastructural creations. More specifically, the area that now constitutes Back Bay was once a great tidal flat that cut off downtown Boston from the rest of the Massachusetts coastline. The bay itself had been an integral part of the local economy for generations, specifically acting as a site for commercial fishing. (Archeological research in Back Bay has uncovered the presence of ancient fish weirs that Native Americans had originally erected millennia ago.) This economic importance eventually stemmed toward the production of hydraulic power, with the Boston and Roxbury Mill Corporation raising a milldam across the basin in 1814. Although hopes were high that the dam could provide power to Boston’s many young factories, it failed to generate anything significant throughout its lifetime. Indeed, the constant tidal changes made the dam’s ability to function inconsistent, resulting in it struggling to become profitable. Furthermore, the dam had spawned a health crisis since its regulation of the bay’s limited seawater prevented runoff from effectively draining out of Boston. Considering the dual crises, state and city officials ruled that the entire bay had to be filled completely during the 1850s. The politicians then created a commission to oversee the task, determining that some 450 acres of land needed to be dredged to resolve the problem. To that end, the commission began filling the entire location with around 3,500 trainloads of gravel per day, starting in 1858.

The work proved to be a massive undertaking, continuing nonstop over the next three decades. However, laborers assigned to the endeavor were triumphant, coming to completely fill Back Bay by 1882. But before the dredging had even finished, city officials were already weighing various options regarding Back Bay’s future. After reviewing several feasible options, the administrators eventually decided the region was best utilized as a residential neighborhood for Boston’s ever-growing population. Prominent architect Arthur Gilman was hence selected to chart a municipal street grid for the nascent Back Bay district on the eve of the American Civil War. Borrowing heavily from the architectural designs of French engineer, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Gilman proceeded to develop a gorgeous collection of tree-lined city blocks that resembled the grand avenues of Paris. Central to Gilman’s design was the historic Commonwealth Avenue, which ran through the center of the area. Remodeled by Gilman to look like the verdant Champs-Élysées, the road functioned as a public park that anchored the whole district. (Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted later modified the layout during the Gilded Age.) Likewise, the structural building plans Gilman crafted displayed the ornate Second Empire-inspired aesthetics that Haussmann had famously implemented in Paris around the same time. Back Bay thus came to mirror the ambiance of the revered City of Lights when construction in the neighborhood finally concluded toward the end of the 19th century.

Its European character soon granted Back Bay a luxurious reputation among the Bostonian elite, leading to many influential community figures moving into the area. The most noteworthy people to relocate to Back Bay were renowned intellectuals like author William Dean Howells and painter John Singer Sargent. Even a few of Boston’s legendary educational institutions—such as Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—debuted their own auxiliary facilities in the neighborhood. The arrival of such affluence had started to gradually change the appearance of Back Bay, too, which produced new buildings that showcased an array of styles ranging from Classical to Colonial Revival. In fact, the architectural distinctiveness had become so great that many Bostonians considered Back Bay to be the city’s most visually stunning place by the beginning of the 20th century! Back Bay has since maintained its prestigious status in the present, serving as home to countless upscale townhouses and apartments. But Back Bay has emerged as a preeminent center for shopping in Boston, specifically the boutiques along its Newbury and Boylston streets. Cultural heritage travelers have enjoyed visiting Back Bay, given the presence of many interesting attractions within its borders, like Copley Square, Trinity Church, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Back Bay is also only a few minutes away from several iconic national landmarks, including Boston Common, the Old State House, and the Old South Meeting House. The neighborhood itself is even a respected historic site, as it bears a listing in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places!

-

About the Architecture +

The Eliot Hotel stands as a brilliant example of Georgian Revival-style architecture. Georgian Revival-style architecture itself is a subset of a much more prominent architectural form known as “Colonial Revival.” Colonial Revival architecture is the most widely used building form in the United States. Widely practiced in America throughout the 19th century, it reached the height of its popularity during the Gilded Age. The movement gained momentum due to the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, which inspired millions of people to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those motivated who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. Structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture, as well as the Georgian Revival-style spinoff, featured such components as: pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined their façades, which were further anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, too. This building form remained immensely popular for years until declining during the late 20th century. Nevertheless, the style has since defined the appearance of numerous historic landmarks all over America, with many preserved with listings in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.