Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Omni La Mansion del Rio San Antonio with its enchanting Spanish Colonial Architecture, celebrated restaurant and elegant accommodations.

Omni La Mansion del Rio, San Antonio, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2010, dates back to 1852.

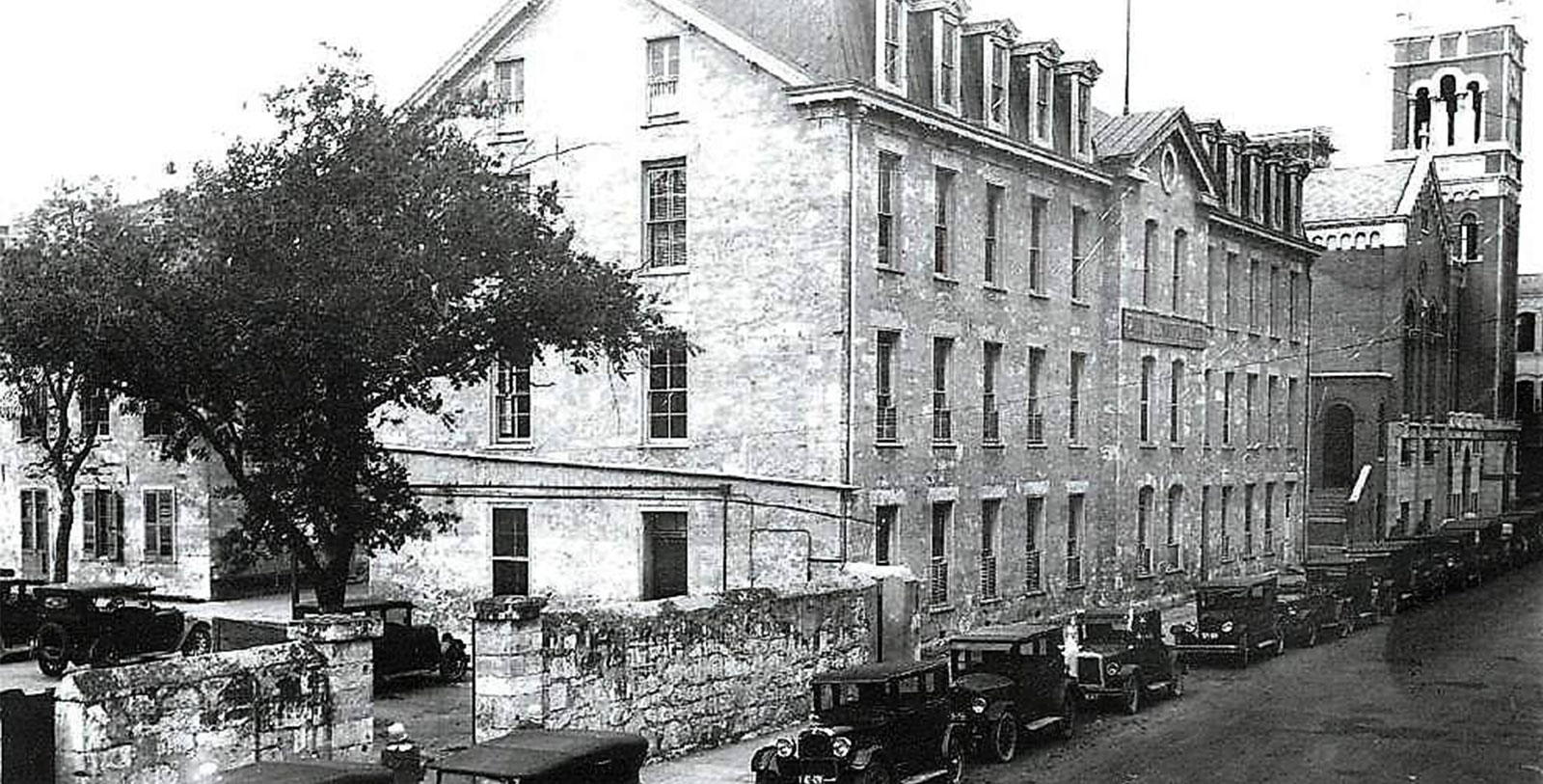

VIEW TIMELINEThe history of the Omni La Mansion del Rio began with a religious order native to San Antonio, Texas. Sixteen years after the fall of the Alamo, four members of the Society of St. Mary arrived in San Antonio to establish a school. They occupied the second floor of a stable on the west side of Military Plaza. Brothers John Baptist Laignoux, Nicholas Koenig, Xavier Mauclerc, and Andrew Edel immediately began construction of a limestone building (said to be 60 x 80 feet) on College Street. The bells of the new school, originally known as St. Mary's Institute, tolled for the first time on March 1, 1853. Roughly a year later, two additional members—Brother Eligium Begrer and Brother Charles Francis— joined the faculty. Winters were hard and sometimes provisions were scarce, but cornbread was always served three times a day washed down by a delicious beverage. Brother Francis (also known as the “Great Builder”) finished the construction at the site with the installation of several additional wings. By 1875, it was one of the largest European building complexes in all of San Antonio. Livestock was kept at Mission Conception, which was also run by the brothers. In the summer, the boarding students spent their time at the mission in somewhat of a camp-like atmosphere.

As the need for education grew, St. Mary's became a junior college and a senior college. In 1894, a new campus was acquired for boarding students, enabling the original facility to increase its enrollment of students. The College Street campus prospered as the “St. Mary's Academy” until 1924, when it became “St. Mary's College.” In 1931, the building became known as St. Mary's University Downtown College. The law school was set up downtown some three years later and remained on College Street until December of 1966. At this time, a former St. Mary's University law student named Patrick J. Kennedy purchased the location and began to develop it into a brand-new luxury hotel. The exterior was made Spanish Colonial Revival-style, with a six-story addition overlooking the nearby San Antonio River. The designs and furnishings were well planned, reflecting the city's cultural ties to both Spain and Mexico. In April 1968, La Mansiόn del Rio opened its doors as the “La Posada Motor Hotel” just in time for “Hemisfiar,” San Antonio's 1968 World Fair. Omni Hotels and Resorts eventually acquired the building in 2006, renaming it as the “Omni La Mansion de Rio.” A member of Historic Hotels of America since 2010, this spectacular holiday destination is now one of San Antonio’s most celebrated landmarks.

-

About the Location +

Omni La Mansion del Rio is located just moments from the renowned San Antonio River Walk. Also known as the “Paseo del Río,” this spectacular cultural destination is a network of pedestrian streets that wind along the center of the San Antonio River. Given its shallow banks, that section of the river had flooded frequently throughout its history, with the worse occurring in 1921. In response, several civic planners debated the ways in which the river could be properly dammed. To that end, architect Robert H.H. Hugman proposed routing a portion of the troubled stretch of water around a beautiful manmade city park. The park itself would feature several walkways lined with old-fashioned streetlamps and would provide additional retail space for various boutique businesses. Debuting later that decade, it quickly became one of the most visited attractions in San Antonio, next to The Alamo and Military Plaza. Efforts to further expand the River Walk occurred during the 1930s, with the Works Progress Administration providing the main source of labor. Various organizations also donated their time toward preserving the River Walk’s beauty, too, such as the San Antonio Advertising Club, the San Antonio Real Estate Board, and the Daughters of the American Revolution’s San Antonio Chapter. Today, the San Antonio River Walk is one of the most vibrant cultural attractions in the entire city.

Many historic neighborhoods reside near the San Antonio River Walk, as well. Among the most prestigious of these districts is the La Villita Historic Arts District, which is located only a few blocks away from the Omni La Mansion del Rio. Originally a Native American settlement, the area spent many decades serving Spanish colonial soldiers throughout the 1700s. Immigrants from across Western Europe then settled the neighborhood shortly after Texas joined the United States during the mid-19th century, forming a robust community of artisans, craftsman, and entrepreneurs. Yet, La Villita suffered greatly from the financial hardships wrought from the Great Depression and became a slum. Fortunately, the National Youth Administration (NYA) worked closely with the San Antonio city government to revitalize the area in 1939. Part of the NYA’s strategy to restore La Villita to its former glory involved establishing a center for arts and crafts within the neighborhood. From this program emerged an energetic commune of artists and intellectuals, who wound up producing all sorts of work ranging from textiles to pottery. Due to its amazing history and contribution to the arts, the village is now recognized by the U.S. Department of the Interior as the “La Villita Historic Arts District.”

-

About the Architecture +

When Patrick J. Kennedy began renovating the St. Mary's University Downtown College campus into the Omni La Mansion del Rio, he chose Spanish Colonial Revival-style architecture as the source for his inspiration. Also known as “Spanish Eclectic,” this architectural form is a representation of themes typically seen in early Spanish colonial settlements. Original Spanish colonial architecture borrowed its design principles from Moorish, Renaissance, and Byzantine forms, which made it incredibly decorative and ornate. The general layout of those structures called for a central courtyard, as well as thick stucco walls that could endure Latin America’s diverse climate. Among the most recognizable features within those colonial buildings involved heavy carved doors, spiraled columns, and gabled red-tile roofs. Architect Bertram Goodhue was the first to widely popularize Spanish Colonial architecture in the United States, spawning a movement to incorporate the style more broadly in American culture at the beginning of the 20th century. Goodhue received a platform for his designs at the Panama-California Exposition on 1915, in which Spanish Colonial architecture was exposed to a national audience for the first time. His push to preserve the form led to a revivalist movement that saw widespread use of Spanish Colonial architecture throughout the country, specifically in California and Florida. Spanish Colonial Revival-style architecture reached its zenith during the early 1930s, although a few American businesspeople—including Patrick J. Kennedy—continued to embrace the form well into the late 20th century.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Battle of the Alamo (1836): The ground upon which the Omni La Mansion del Rio sits was once part of the famed Battle of the Alamo. The Battle of the Alamo involved soldiers of the Mexican Republic besieging a force of Texan patriots inside an old Franciscan mission known locally as The Alamo. A mixture of Mexican and American settlers known as “Texians,” the defenders had originally seized the site at the onset of the Texas War for Independence in December of 1835. They were a volunteer force led by Colonel James Bowie and Lieutenant Colonel William B. Travis. Among their number included the legendary frontiersmen and Tennessee politician, Davy Crockett. Mexican general Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana decided to take the fort back, leading a sizable army of several thousand well-trained soldiers into San Antonio on February 23, 1836. The Texians were greatly outnumbered, though, as their ranks only featured some 200 men. Santa Ana then surrounded the fort for 13 days, engaging in a battle of attrition with The Alamo’s garrison.

Still, the Texians hung on despite the precariousness of their situation. The Mexican Army eventually attacked The Alamo on March 13, killing most of the defenders in an overwhelming assault. Few survived due to Santa Ana’s order that no Texian rebel be spared. But while the battle resulted in a tactical victory for Santa Ana, it wound up galvanizing even stronger resistance to Mexican rule in Texas. Sam Houston and a force of 800 Texians routed Santa Anna and his men at the Battle of San Jacinto nearly a month later, yelling the words “Remember the Alamo” throughout the fight. Texas subsequently earned its independence from Mexico later that year. The phrase “Remember the Alamo” was used again by American troops during the Mexican American War, in which Texas was an active participant. The battle itself would become a symbol for patriotic self-sacrifice in American memory, often being immortalized in various forms of literature and art. Hollywood even presented a fictionalized adaptation of the fight in the 1960 film, The Alamo.

HemisFair ’68: HemisFair ’68 was the official 1968 World’s Fair held in San Antonio from April to October in 1968. The heir to a long tradition that dated back to the 1850s, the theme for the 1968 World’s Fair was, “The Confluence of Civilizations in the Americas.” More than 30 nations and 15 corporations hosted pavilions at the fair that year. HemisFair ’68 cost some $156 million to finance, with many of its exhibitions constructed across some 96 acres in downtown San Antonio. City officials also extended the River Walk by a quarter of the mile in order to link it to the main HemisFair fairgrounds. The main displays at HemisFair showcased Central American culture, as well as that from Brazil, Argentina, and Peru. A total of 6.3 million people attended the event, although those numbers fell below the expected turnout. Yet, a few prominent Americans did visit the event, including First Lady Ladybird Johnson and Texas Governor John Connolly. While most of the HemisFair fairgrounds were deconstructed or repurposed over the next several decades, a couple of its iconic structures managed to avoid the wrecking ball. Perhaps the greatest of its attractions left standing today is the Tower of the Americas, which still rates as the tallest building in all of San Antonio.