Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Cavallo Point, which represented the rebirth of the dilapidated United States Army during the Endicott Period.

10 Years at Cavallo Point

Watch this wonderful viewing celebrating the 10th anniversary of the historic Cavallo Point. Viewers will enjoy seeing the historical photographs of the lodge contrast with contemporary images of the grounds from the present.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2009, Cavallo Point is one of the best holiday destinations in the greater San Francisco area. This fantastic vacation getaway was once a beautiful housing complex that cared for the soldiers stationed at the historic Fort Baker for more than a century. Fort Baker itself used to be a massive military base that spanned much of the local shoreline. Mostly developed throughout the first decade of the 1900s, the fort was actually one of several military installations built at the behest of the War Department to protect San Francisco’s strategically important harbors. For many years, the U.S. government had assessed the strength of its costal defense apparatus, and determined that it was in dire need to rehabilitation. Furthermore, relations between the United States and Spain had greatly deteriorated in the 1890s, prompting the War Department to expedite its plans. As such, the War Department provided an extensive list of suggestions to both expand and modernize all of their forts near both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The Marin Headlands became a primary focus for the military, with construction starting on the earliest fortifications in 1897. Over the next several years, the War Department sponsored the creation of multiple battlements that included Batteries Yates, Spencer, Kirby, Duncan, Wagner, and a dozen other. Most of the structures were sprawling concrete bunkers, which encased massive pieces of ordnance. (The architectural style itself is referred to as “Endicott Period” architecture, as the aesthetic first appeared under the watch of William C. Endicott, the Secretary of War during President Grover Cleveland’s second administration.)

The nucleus of Fort Baker was among the first military facilities constructed by the War Department in the Marin Headlands, with Fort Barry eventually joining it shortly thereafter. Work on Fort Baker began in 1901 and lasted for a total of nine years. While some of the batteries did come to comprise Fort Baker, most of its structures provided housing for the soldiers stationed in the area. The new buildings created at the time displayed Colonial Revival-style architecture, and were stationed around the base’s main parade ground. The design of the dwellings reflected the desire of the War Department to enhance both the physical and mental well-being of its soldiers. It hoped that the new homes would make the servicemen feel both relaxed and secure. The barracks themselves featured the latest amenities of the age, too, such as heat ventilation and indoor plumbing. And as with most other military bases, the officers often had their own homes where they could live with their families. Additionally, Fort Baker also contained a 12-bedroom hospital, a gymnasium, and a post exchange that had a general store and lunchroom. There was even a bowling alley onsite! Members of the Coast Artillery Corps moved into the base once construction concluded in 1910. The Coast Artillery Corps would remain at Fort Baker for the next few decades, manning its humungous guns that helped safeguard all the naval passage into and out of San Francisco.

As the United States entered World War II after the Attack on Pearl Harbor, the War Department created the Harbor Defense of San Francisco to better coordinate the region’s protection from foreign threats. The new organization was given complete operational control over many military installations, including Fort Baker and its neighbors, Forts Barry and Fort Cronkhite. In addition to its imposing naval cannons, Fort Baker served as the headquarters for the Harbor Defense’s mine depot. Soldiers assigned to the Coastal Artillery Corps worked inside the depot, where they prepared the ordinance for use in the bay. Every man would load nearly 800 pounds of dynamite into each mine just to get it ready! As the war raged, Fort Baker gradually transitioned away from naval defense and toward anti-air resistance. The U.S. Sixth Army Air Defense Command Region also relocated its headquarters to Fort Baker toward the end of the conflict, as well. The citadel continued to guard San Francisco for many years thereafter, serving as the home of the Sixth ARADCOM Region. (The Sixth ARADCOM Region oversaw the administration of 12 permanent launch sites of Nike missiles stationed across the area.) Then, in the 1970s, it acted as the base for the 91st Infantry Division, known within the U.S. Army as the "The Wild West Division.” A training formation, the unit used the grounds to provide elementary instruction to those destined for posts in the Army National Guard, the Army Reserve Combat Support, and the Combat Service Support.

When the Cold War finally wound down in the 1980s, Congress started drafting plans that looked toward demobilizing much of America’s standing military. Those plans included the deactivation of the country’s military bases, save for the most critical. Congress outlined the particular aspects of its strategy within its Base Realignment and Closure program, which ultimately decommissioned some 350 military installations throughout the United States. Fort Baker was one of many facilities that did not make the cut and began the process of shutting down. In 1995, Congress transferred the facility to the control of the National Park Service, making it a part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. By 2000, the transfer was complete, with the entire 91st Infantry Division relocated to Camp Parks. Then, five years later, the National Park Service and a few local real estate developers decided to transform a sizable portion of Fort Baker into a secluded retreat and conference center. Over the next several months, the business group converted 13 of the historic military houses—as well as a couple other buildings—and renovated them into a wonderful vacation getaway called “Cavallo Point.” (The name specifically referenced a nearby geological formation that the Spanish had called “Cavallo,” after watching wild horses roam its crest in the 18th century.) Cavallo Point—and Fort Baker as a whole—are now some of the most often-visited places in central California, attracting hundreds of people each year.

-

About the Location +

Located in the Marin Headlands near a coastal inlet known as “Horseshoe Bay,” Fort Baker sits across San Francisco Bay from the Presidio of San Francisco. Thousands of cars pass by this scene destination annually, as it is also just moments away from the celebrated Golden Gate Bridge. But years before either Fort Baker ever existed, the Marin Headlands were inhabited for centuries by the people of the Miwok tribe. The area was sparsely populated for years thereafter, even after the Spanish began colonizing present-day California in the 1700s. Explorers and sailors still passed by the region on occasion though, as they guided their ships into the safety of San Francisco’s harbor. In fact, those Spanish mariners were among the first to give the area a name. One such sea captain actually began calling the locale “Punta de Caballo,” after he had watched herds of wild horses roam throughout the bluffs on a voyage in 1777. The title stuck and the Marin Headlands were referred to as the “Punta de Caballo” for generations. American settlers then began to anglicize the name as they flooded into California a century later, mispronouncing the “b” in “caballo” for a “v.” As such, the pioneers across the greater San Francisco area started calling the site “Cavallo Point.”

In the 1830s, most of the Marin Headlands—and the larger Marin Peninsula—were owned by William A. Richardson, an English mariner who moved to California as a young man the decade prior. Endearing himself with the local colonial governor, Richardson received a massive land grant that amounted to thousands of acres. He eventually created an estate called the “Rancho Sauselito” near the site of today’s City of Sausalito. Yet, the vicinity of the Marin Headlands largely remained a wilderness, even as the several communities sprang up further north. By this point, the country had just emerged out of a destructive civil war. In the wake of the conflict, the War Department began reviewing its coastal defense network on both sides of the continent. Over the next thirty years, military officers in Washington commissioned the development of numerous military installations across the United States. Among the areas it decided to develop was the Marin Headlands, which the federal government finally acquired in 1866. (President Millard Fillmore had originally tried to obtain the area in 1850, but lengthy litigation delayed the transfer for some time.) But the military did not break ground at the site until the end of the century, as war loomed on the horizon between America and Spain. The first coastal batteries appeared in the late 1890s, which covered the whole shoreline from Horseshoe Bay to the Bonita Channel. The batteries themselves were concrete bunkers that encased massive pieces of ordnance in a style that historians today refer to as “Endicott.” The War Department hoped that the cannons would protect all shipping traffic into the area in concert with the much larger Presidio of San Francisco directly across the Golden Gate.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the War Department had also started erecting a series of barracks and administrative buildings to serve the troops stationed at the defenses. Those new structures coalesced into individual military complexes that had control over select groups of batteries. The first base constructed was “Fort Baker” in 1901, which was followed almost a decade later by “Fort Barry.” The two installations operated together over the next 30 years, serving as the garrison for the soldiers of the Coastal Artillery Corps. A third base near Bonita Cove called “Fort Cronkhite” opened in 1941, after the War Department spent the previous two years creating it in anticipation of a massive military buildup. That event transpired just a few months afterward with the Attack on Pearl Harbor in December. The three bases mainly guarded the maritime approaches into the bay, via a new organization called the “Harbor Defense of San Francisco.” Over time, the coastal guns were replaced with anti-aircraft units, as the War Department determined that modern airpower had rendered conventional Endicott fortress useless. And toward the end of the conflict, the Sixth U.S. Army operated the headquarters of its Air Defense Command from inside Fort Baker. The Sixth U.S. Army was eventually replaced by the Sixth ARADCOM Region, which administered 12 permanent anti-aircraft missile silos scattered throughout the countryside. Yet, ARADOCM left in the 1970s, with the 91st Infantry Division taking its place. A veteran unit from World War II, the 91st Infantry Division had been changed into a reserve formation that mainly trained new recruits for service in the Army National Guard, the Army Reserve Combat Support, and the Combat Service Support.

When the Cold War finally wound down in the 1980s, Congress began assessing the relevance of the nation’s many military bases. As such, it determined to shut down all three forts over the span of the next decade. All of the ordinance was either relocated and destroyed, and the members of the 91st Infantry Division moved to Camps Parks on the other side of San Francisco Bay. In 1995, the federal government ultimately decided to give all three installations to the National Park Service to operate as part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Congress has originally created the destination in 1972, in order to make the national parks more accessible to people living in crowded metropolitan communities. All three forts were thus added to the 75,000 acres of land that constituted the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Today, the remnants of the three bases serve as historical attractions within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, alongside the likes of the Muir Woods National Monument, the Presidio of San Francisco, and even the famous Alcatraz Island. The U.S. Department of the Interior has even listed all three installations on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as a historic district called “Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite.”

-

About the Architecture +

When the War Department began creating Fort Baker at the beginning of the 20th century, it endeavored to use Colonial Revival-style architecture as its primary source of inspiration. Conventional American military thought called for the greater care of the nation’s soldiers. The War Department thus endeavored to create accommodating, technologically advanced barracks for its men to use. The structures at Fort Baker was no exception to the rule, including the unique buildings that currently constitute today’s Cavallo Point. The War Department had specifically hoped that Colonial Revival architecture would make the soldiers feel as if they were still at home. Colonial Revival architecture itself was also the most widely used building form in the entire United States at the time. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined Colonial Revival-style façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, as well. This building form remained immensely popular for years until largely petering out in late-20th century. Nevertheless, architects today still rely upon Colonial Revival architecture, using the form to construct all kinds of residential buildings and commercial complexes.

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

The Enforcer (1976)

Star Trek: Enterprise (2001 – 2005)

The Amazing Race 2 (2002)

Guest Historian Series

Read Guest Historian SeriesNobody Asked Me, But… No.235;

Hotel History: Cavallo Point, The Lodge at the Golden Gate (1901)

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

The history of the spectacular site of the Lodge at the Golden Gate commences with the coastal Miwok Indian tribes who occupied Horseshoe Cove long before there was a Golden Gate Bridge. In 1866, the U.S. Army acquired the site for a military base to fortify the north side of the harbor entrance. The twenty-four buildings around the ten-acre parade ground at Fort Baker were developed between 1901 and 1915.

Designed in the Colonial Revival architectural style as permanent housing for the Coast Artillary Corps (active from 1907-1950), Fort Baker was a big improvement over former dilapidated army facilities. It offered clean water, modern plumbing and well-designed living quarters. The Army added a gymnasium, reading room, bowling alley, post exchange and a small hospital.

As the United States entered World War II, the army created the harbor defenses of San Francisco which commanded most of the Bay Area fortifications including Fort Baker, Fort Cronkhite and Fort Barry. Fort Baker's Horseshoe Cove became the hub of the Harbor Defense's mine depot, where metal mines with 800 pounds of TNT were planted out at sea. Horseshoe Cove also was the home of the Marine Repair Shop which maintained the civilian boats that were conscripted for use in the mine depot.

After the end of World War II, the threat of air attack surpassed that of naval assault and Fort Baker became the headquarters for the Sixth U.S. Army Air Defense Command Region which housed and deployed anti-aircraft missiles.

From 1970 until the 1990s, the 91st Infantry Division, or "The Wild West Division," was stationed at Fort Baker under the command of the Travis Air Force Base. The 91st had been active in both world wars, but was deactivated in 1945. One year later, the 91st was reactivated as a part of the U.S. Army Reserve. The Wild West Division was responsible for creating the training exercises used by the Army National Guard, the Army Reserve Combat Support, and the Combat Service Support.

During this era, Fort Baker was designated for transfer to the National Park Service when it was no longer needed as a military base. In 1973, it was officially listed as a Historic District in the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1995, the armed forces transferred the land to the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. By the end of 2000, there were no soldiers left at Fort Baker as the 91st moved on to Camp Parks, California. As of 2002, Fort Baker was no longer a military post; it was a park.

In January of 2005, an agreement was reached between the city, the National Park Service, and developers that Fort Baker be renovated and turned into a hotel and conference center. Thirteen historic lodgings have been renovated as well as seven historic common buildings.

Cavallo Point - The Lodge at the Golden Gate opened in 2008 on 45 acres with half of the 142 lodging units located in landmark buildings on the 10-acre parade ground - most offering spectacular views of San Francisco and the Bay. The other half are 21st century units designed for environmental sustainability with commanding views of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Cavallo Point provides more than 15,000 square feet of meeting space to host seminars, educational programs and corporate events. The lodge's Healing Arts Center and Spa has 12 treatment rooms, a heated basking pool and a medicinal herb garden where guests can pick their own ingredients for treatments. The Murray Circle restaurant has a Michelin star and serves French-inspired California cuisine and has a 13,000-bottle wine cellar.

The lodge also serves as the home for the Institute at the Golden Gate, an environmental organization that is a project of the Golden Gate National Park Conservancy and the National Parks Service. Cavallo Point offers an ambitious program of cooking classes including a soufflé workshop, cooking from the Farmer's Market and a chocolate workshop.

Fodor's Review sums up Cavallo Point in these glowing terms:

"Set in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, this luxury hotel and resort with a one-of-a-kind location on a former army post contains well-appointed eco-friendly rooms. Most of them overlook a massive lawn with stunning views of the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco Bay. Murray Circle, the on-site restaurant, uses top-notch California ingredients and has an impressive wine cellar, and the neighboring casual bar offers food and drink on a large porch."

Fort Baker is listed as a Historic District in the National Register of Historic Places and Cavallo Point was named one of ten "New Green American Landmarks" by Travel & Leisure. Cavallo Point - The Lodge at the Golden Gate is a member of Historic Hotels of America, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

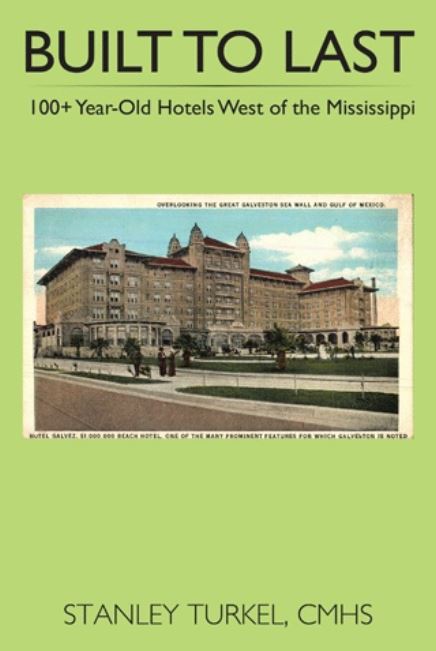

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.