Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

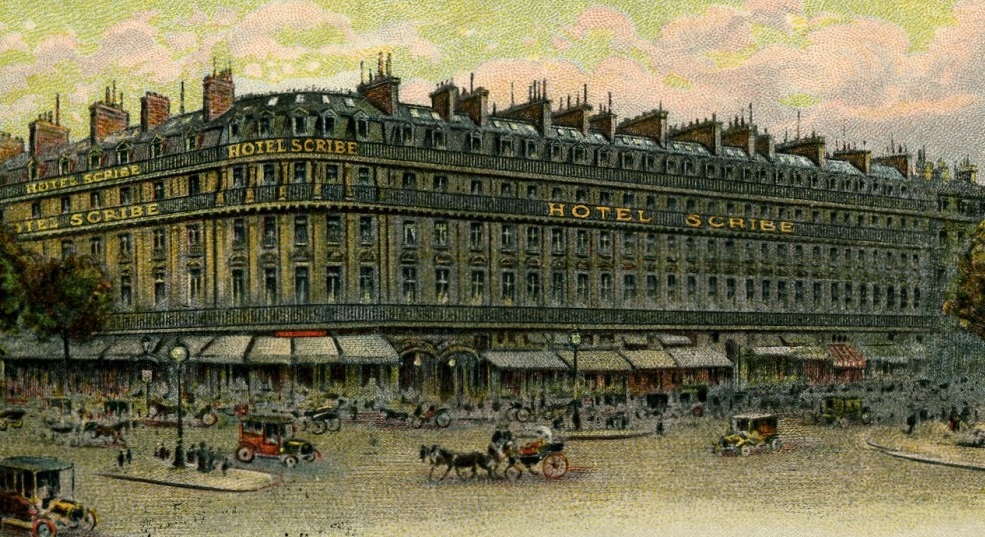

Discover the Hotel Scribe Paris Opera By Sofitel, which was once home to the illustrious Jockey Club de Paris.

Hôtel Scribe Paris Opera by Sofitel, a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2018, dates back to 1861.

VIEW TIMELINELa Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon by the Lumière Brothers

Watch one of the first films ever made, which had its debut inside the precursor to the Hôtel Scribe’s Café Lumière.

WATCH NOWThroughout much of the 19th century, equestrian organizations known as “jockey clubs” sprang up across the world. Those groups tasked themselves with the regulation of professional horse-racing on a national scale, establishing criteria that directly affected the administration of the sport. Jockey Clubs originally founded everything from breeding standards to competition bylaws. While governmental agencies have assumed the responsibility for supervising horse-racing in recent years, the guidelines that the clubs first created still exist in some form today. But, the groups also doubled as a place where members of high-society could gather. In France, the Jockey Club de Paris was the choice organization for the country’s social elite. Founded during the 1830s, this social club quickly emerged as a dominant cultural force in the French capital. It bounced around numerous homes throughout the city a ceaseless pursuit for a venue that would appropriately reflect the grandeur of its members. After a long search, the Jockey Club de Paris eventually settled on a gorgeous hotel called the “Hôtel Scribe” in 1863. Finished some two years prior to the arrival of the Jockey Club de Paris, the Hôtel Scribe was one of the many creations of the famed French civil engineer, Georges-Eugéne Haussmann. Named after the renowned French author Augustin Eugène Scribe, the hotel was originally developed to help enhance the opulence of Paris’s new Opera District. As such, it quickly emerged as one of the city’s most prestigious hotels. But when the Jockey Club de Paris decided to use the first two floors of the location as their headquarters, the Hôtel Scribe’s reputation was catapulted to new heights. The hotel soon became closely associated with its new luxurious tenants, creating a sophisticated charm that impressed its many visitors. By the turn of the century, the Hôtel Scribe was among the most recognizable structures in Paris’s ninth arrondissement.

The Hôtel Scribe successfully maintained its revered status even after the Jockey Club de Paris decided to relocate yet again in 1925. Countless travelers remained fascinated by the hotel’s alluring character, arriving in droves to experience its legendary accommodations. Well-known international celebrities soon began to arrive at the Hôtel Scribe as well, transforming the location into a regular haunt for famous artists, intellectuals, and entertainers. Legendary figures like Marcel Proust, Jules Verne, and Serge Diaghilev have all resided at the hotel at one point or another during its venerable history. The Hôtel Scribe even served as the Parisian residence for the iconic French-American actress, Josephine Baker. But the Hôtel Scribe eventually fell on hard times a few decades later when World War II ravaged the continent. Shortly after Paris fell to the Germans in the summer of 1940, the building emerged as a local headquarters for Nazi propagandists. It subsequently fulfilled that role for many years, until the Allies successfully liberated the city for years later. Soon enough, several hundred Allied newsmen used the Hôtel Scribe as the base of operations for their own journalistic publications, writing three million words’ worth of material every week! Sofitel now proudly manages this fabulous historical building as the “Hôtel Scribe Paris Opéra” in honor of its storied legacy. Under Sofitel’s watchful eye, the architectural firm “Wilson Associates” and its artistic director, Tristian Auter, oversaw a massive renovation effort. Their work was comprehensive, magnificently preserving the building’s rich heritage for future generations to appreciate. This brilliant historic hotel has also been a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2018, inducted alongside several dozen other holiday destinations within the Sofitel brand.

-

About the Location +

Known as the “City of Lights,” Paris is one of the most famous metropolises in the entire world. Its history harkens back centuries, beginning with the arrival of the Celtic Parisii nearly two millennia ago. They specifically settled around a small island within the Seine that later would be called the “Île de la Cité.” Over time, the small Parisii community emerged as one of the major trading hubs in the region, entertaining merchants from places as far south as the Iberian Peninsula. Its prosperity eventually attracted the attention of the Roman Empire, though, which had been conquering the area of modern-day France amid a conflict known to history as the “Gallic Wars.” Once the Romans subjugated the Parisii in the 1st century BC, they immediately began to redevelop the entire area. They subsequently constructed a much larger settlement that they christened as “Lutetia Parisiorum,” which literally meant “Lutetia of the Parisii.” But unlike the earlier Celtic town, the new Roman city gradually concentrated along the Seine’s left bank. Nevertheless, great wealth continued to flow into the community, leading to a massive wave of construction that expanded its size exponentially. Dozens of magnificent structures quickly dominated the local skyline, including several theaters, temples, baths, and storefronts. Lutetia even entertained a sprawling forum and a spacious amphitheater. (Christianity also arrived in the region, too, with the semi-mythical Saint Davis functioning as its first official bishop during the 3rd century AD.)

But Lutetia’s golden years came to an end when the Roman Empire gradually collapsed throughout the 4th century. Now known exclusively by the name “Parisius,” it soon fell prey to roving bands of Huns—and later Vikings—who prowled across Western Europe with the absence of Roman influence. A group of Germanic people known as the Franks eventually asserted their dominance, who were led by a mighty nobleman named “Clovis.” Clovis’ descendants—known as the “Merovingians”—managed to finally reintroduce some stability, ruling over much of France from Parisius until their successors—the “Carolingians”—relocated the capital to Aachen. The city and its surrounding environs soon reverted to the status of a medieval “county,” which struggled to protect itself from raiders traveling along the Seine. Thankfully, the community was finally spared when one of its ruling counts, Odo, fought off the Vikings once and for all during the Siege of Paris in the late 9th century. (Odo and his line of Robertians would briefly rule over France afterward.) Yet, the city—known by this point as “Paris”—did not truly return to political and cultural relevance until the election of Hugh Capet as French monarch in 987. His own royal dynasty would subsequently rule over France for the next four centuries, with two cadet branches—the Valois and the Bourbons—succeeding it for another five.

Under the Capetians and their successors, Paris reemerged as the cultural capital of France. The monarchs helped directly spawn its rapid growth, commissioning the dredging of the Seine’s right bank for the creation of new neighborhoods. In fact, a whole new massive marketplace debuted in Paris (Les Halles), which subsequently replaced the smaller, older one situated at the Île de la Cité. Still, the Île de la Cité remained the essential “heart” of the city, serving as the site of both the famous Notre-Dame Cathedral and the royal palace, the “Palais de la Cité.” Furthermore, the city quickly became protected by a massive fortress called the “Louvre,” which guarded against foreign military excursions at the height of the Hundred Years War. Yet, despite the imposing defenses that resided within Paris, armies led by the rival Burgundians and English captured the city in the first half of the 15th century. But once the English and their allies were finally defeated in 1453, Paris reverted back to its role as the bastion of the French monarchy. French kings continued to expand upon the city greatly, focusing more on its appearance rather than its military significance. Grander buildings subsequently opened in Paris, including the famed Pont Neuf, the Places des Vosges, and an extension of the Louvre called the “Tuileries Palace.”

Paris once again ceased functioning as the official French capital when King Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” moved his entire court to the Palace of Versailles just beyond the city limits. Still, Paris remained culturally significant, with all kinds of institutions devoted to the arts and sciences debuting inside it. The city, thus, became one of the major intellectual centers for the Enlightenment, as many authors, scientists, and philosophers quickly called the destination home. More beautiful buildings opened as such, including the Place Vendôme, the Places des Victories, and Les Invalides. Even the Champs-Élysées—the main thoroughfare through Paris—underwent a dramatic renovation, as all kinds of gorgeous mansions and shrubbery lined the road. But France began to suffer from a prolonged economic crisis that fanned the flames of discontent toward the French crown. As such, Paris was the epicenter for the French Revolution when it finally erupted in 1789. King Louis XVI and his family were then brought to the city, where they were tried as traitors and executed at the height of the revolution’s Reign of Terror. After a decade of continued political instability, Napoleon Bonaparte—a successful revolutionary general from Corsica—seized power as First Consul, and then Emperor. And while Napoleon fought a series of wars of conquest across Europe, he also proceeded to fully restore Paris back to the capital of France. He specifically bestowed it with his royal patronage that led to a new wave of construction throughout the city. As such, he constructed dozens of new iconic landmarks, like the Arc de Triomphe, the Canal de l’Ourcq, and the Pont des Arts.

Paris continued to permanently act as the official French capital, even after Napoleon’s final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Yet, the city truly began to take on its current appearance and prestige during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte III, who had risen to power in the wake of the tumultuous Revolutions of 1848. Selecting a French official named Georges-Eugène Haussmann, he commissioned a massive building project that sought to transform downtown Paris into what he considered to be a “modern” western city. Its greatest legacy were the buildings that Haussmann constructed, which displayed his patented “Second Empire” architecture. (It is this architectural style that mainly defines Paris’ cityscape to this very day!) Paris continued to endure as a beacon of French—and Western—culture for decades thereafter, even when it was periodically beset by war during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It hosted two magnificent international expositions, such as the 1889 Universal Exposition and the 1900 Universal Exposition, which further solidified Paris’ emerging status as Europe’s cultural capital. (The Eiffel Tower—Paris’ most iconic landmark—debuted the central attraction to one of those fairs.) Many intellectuals from around Europe also continued to move to Paris, too, making it the birthplace of such artistic movements like “Naturalism,” “Impressionism,” “Cubism,” and many other art forms. Paris today still embraces its place in the world as a purveyor of culture, countless museums, art galleries, and theaters attracting thousands of visitors each year. Its historic downtown—centered around the Île de la Cité—have even been designated as one of the most prolific UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Truly few places are better throughout the world for a wonderful, cultural heritage experience that the magnificent “City of Lights.”

-

About the Architecture +

Constructed in the early 1860s, the Hôtel Scribe Paris Opera by Sofitel displays some of the finest “Second Empire” architecture in all of Paris. Also known simply as “mansard style,” Second Empire architecture first emerged in Paris at the height of the reign of Emperor Napoléon III. Born Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, he was the nephew of the legendary Napoléon Bonaparte of the French Revolution. He rose to power by serving as France’s president before making himself its monarch by the middle of the 1800s. Nevertheless, his reign saw a brief restoration in French national pride that was accompanied by a cultural renaissance that affected everything from the arts to the sciences. One the areas that saw this development was architecture. Napoléon III had taken a particular interest with architectural projects at the time, going as far as to commission the complete redesign of Paris’ central cityscape. He subsequently appointed engineer Georges-Eugène Haussmann for the project, instructing the latter to create a new generation of buildings that could accommodate the city’s swelling population. Largely borrowing design elements from the French Renaissance of the 16th century, Haussmann essentially created a brand-new architectural form that soon defined the appearance of Paris. While the project itself only lasted from 1853 to 1870, its impact was felt throughout the world for many years thereafter. Haussmann’s new form quickly appeared across France, as well as many other countries throughout Europe, including Belgium, Austria, and England. Furthermore, the architecture quickly emerged in North America, finding a popular audience in both the United States and Canada. Many hoteliers like Frank Jones saw the fabulous design aesthetics of Second Empire architecture and copied it for their own structures throughout the remainder of the 19th century.

Second Empire architecture was specifically meant for larger structures that could easily showcase its ornate features and grandiose materials. Architects, business owners and other professionals who embraced the form believed that it represented the best of modernity and human progress. This idea especially found an audience in the America, where society was largely perceived to be on an upward path of collective mobility. (In fact, the architecture had become so enmeshed in American society that some took to calling it “General Grant” style.) The form looked similar to the equally popular Italianate-style, in which it embraced an asymmetrical floor plan that was rooted to either a “U” or “L” shaped foundation. The buildings usually stood two to three stories, although some commercial structures—like hotels—exceeded that threshold. Large ornate windows proliferated across the facade, while a brilliant warp-around porch occasionally functioned as the main entry point. The porches would also have several outstanding columns, designed to appear smooth in appearance. Every window and doorway featured decorative brackets that typically sat underneath lavish cornices and overhanging eaves. Gorgeous towers known and cupolas typically resided toward the top of the building, too. Yet, Second Empire architecture broke from Italianate in one major way—the appearance of the roof. Architects always incorporated a mansard-style roof onto the building, which consisted of a four-sided, gambrel-style structure that was divided among two different slopes. Set at a much longer, steeper angle than the first, the second slope often contained many beautiful dormer windows. The mansard roof became a central component to Second Empire architecture after Georges-Eugène Haussmann and his fellow French architects starting using it for their own designs. They had specifically sought to copy the mansard roof of The Louvre, which the renowned François Mansart had created back at the height of the French Renaissance.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Lumière Brothers Film Screening (1895): On March 22, 1895, the Hôtel Scribe’s Café Lumière was host to cinematic history. Two aspiring amateur filmmakers, Auguste and Louis Lumière, had spent the previous months refining a new machine that they called the “cinematographe.” Completely ahead of its time, the device was a hand-cranked camera-projector that could show a sequence of moving images before an audience of several people. In fact, the cinematographe was an enhancement over Thomas Edison’s kinetograph, which had lacked a projector and was only meant for single-person viewership. The men proceeded to film ten different movies across Lyon, France, with 35mm film shot at around a dozen of frames per second. The movies they created were incredibly short, as well, numbering around a minute in length each. Furthermore, the Lumière did not provide any sound with the film strips, nor did they offer any form of closed captioning.

Nevertheless, the movies that the brothers produced were nothing short of revolutionary. Impressed, they yearned to share their invention with their fellow countrymen. Seeking the perfect venue within which to debut their movies, they selected a dimly lit room in the basement of the Grand Café. (The café itself was a quaint restaurant located just off of the Boulevard des Capucines near the Place de l'Opéra, in what is now the Café Lumière.) Together, the men then ran their first film, entitled, La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon, which showcased a large group of laborers leaving a factory at closing time. The Lumières then proceeded to show the following nine films over the next few minutes:

- Le Jardinier

- Le Débarquement du Congrès de Photographie à Lyon

- La Voltige

- La Pêche aux poissons rouges

- Les Forgerons

- Repas de bébé

- Le Saut à la couverture

- La Places des Cordeliers à Lyon

- La Mer (Baignade en mer)

Their presentation not only spawned a surge of interest about motion pictures in France, but throughout the rest of the world, too. In America, demand for the Lumières films became so great that they even opened some of the first movie theaters to host their productions. The nascent film industry also rapidly began to take off throughout the West, as many other ambitious filmmakers began dispatching crews across the globe to create similar movies. It is thanks to the imagination of the Lumière brothers that people today can enjoy the rich heritage of the modern film industry.

Liberation of Paris (1944): On August 25, five Canadian journalists delicately guided their jeeps through the throngs of enthusiastic Parisians who had endured years of oppression under German occupation. The men had recently been assigned to work at the Hôtel Scribe, which had just served as the administrative offices for Nazi propagandists stationed in Paris. The Canadians printed their first article upon their arrival at the building, which detailed the city’s liberation mere hours before. (The first unit to arrive in Paris was the French 2nd Armored Division, led by General Philippe Leclerc of the French Free Forces.) Over the next few months, an army of some 200 to 500 newsmen from several Allied nations set up operations inside the hotel’s interior lobby, writing three million words’ worth of material every week! But that was not all. The correspondents who reported from the building also produced 100,000 feet of movie reels, as well as 35,000 still pictures within the same amount of time. Soon enough, the constant patter of telegraph and typewriter keys gave the space a unique ambiance that was both eerie and fascinating. Among the journalists known to haunt the Hôtel Scribe—particularly its exclusive bar after hours—were famous reporters like Ernie Pyle, Walter Cronkite, Robert Capa, Janet Flanner, Lee Miller, Marguerite Higgins, Irwin Shaw, and Charles Collingwood. Even the great Ernest Hemingway stopped by to chat with the reports from time to time. The Hôtel Scribe continued to serve as one of the main headquarters for Allied reporters for the rest of the war, hosting all kinds of journalists right up until the surrender of Germany on V-E Day the following year.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Marcel Proust, author best remembered for his novel, In Search of Lost Time.

Jules Verne, author known for such novels like Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, and Around the World in Eighty Days.

Ernest Hemingway, author known for writing such books like A Farwell to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea.

Irwin Shaw, journalist and author known for his novels, The Young Lions and Rich Man, Poor Man.

Serge Diaghilev, art critique and ballet impresario who founded the famous Ballets Russes.

Louis Vuitton, fashion designer and businessperson who founded the luxury goods company that bears his name today.

Josephine Baker, celebrated American-French icon from the Jazz Age and renowned Civil Rights leader.

Ernie Pyle, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist who is best known for his articles about the ordinary American soldier.

Walter Cronkite, broadcast journalist best known for hosting CBS Evening News during the 1960s and 1970s.

Janet Flanner, journalist who worked at the New Yorker for fives decades, writing under the pen name “Genêt.”

Lee Miller, journalist best remembered for her wartime photographic work for Vogue during World War II.

Marguerite Higgins, war correspondent known for her work with both the New York Herald Tribune and Newsday.

Charles Collingwood, journalist part of CBS’ group of war correspondents known as the “Murrow Boys.”

Robert Capa, war correspondent considered by some to be the greatest combat photographer to ever live.

Martha Gellhorn, journalist who is best remembered today as one of the greatest war correspondents of the 20th century.

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon (1895)

Le Jardinier (1895)

Le Débarquement du Congrès de Photographie à Lyon (1895)

La Voltige (1895)

La Pêche aux poissons rouges (1895)

Les Forgerons (1895)

Repas de bébé (1895)

Le Saut à la couverture (1895)

La Places des Cordeliers à Lyon (1895)

La Mer (Baignade en mer) (1895)

-

Women in History +

Josephine Baker: Born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1906, Josephine Baker would rise to become on the most renowned entertainers in the 20th century. Her parents, Carrie McDonald and Eddie Carson, were both amateur performers themselves, who traveled across the Midwest to appear in a number of vaudeville productions. While neither of their careers ever became well-known, they nonetheless left a profound impact upon Baker. At often times, her parents would bring the young girl on stage, where she would dance before the large audiences. Her father eventually left the family, though, forcing Baker to find numerous odd jobs to help support the family. But the allure of the stage never weakened and she ran away from home to join an African American theater troupe when she was just 15. Over the next several years, Baker would journey around the United States, appearing first in comedic skits and then concerts once the troupe split apart. She soon found her calling as a dancer, using her wit and humor as a means to enchant countless spectators throughout America. But despite being such a huge draw, Baker often had to perform in front of segregated crowds—a terrible experience that stayed with her for the rest of her life.

She soon wed several men, including Willie Baker, whose name she kept all her life. (Another husband, Jean Lion, granted Baker her eventual French citizenship.) Unlike many other women of the era, Baker had no trouble establishing her own financial independence and could freely leave a relationship if it began to turn toxic. Nevertheless, Baker pushed ahead with her acting career, moving to New York City amid the Harlem Renaissance before heading across the Atlantic to Paris. Initially finding a home at the La Revue Nègreclosed, she soon made a name for herself after starring in La Folie du Jour at the Follies-Bergère Theater. The socially progressive Parisian society received Baker’s performances with great enthusiasm, elevating her to one of France’s most popular starlets. She became especially renowned for her more eye-popping dance routines, particularly a one set that involved her wearing a costume of 16 bananas. Her talents also earned her the roles in two European films, Zou-Zou and Prince Tam-Tam. Baker was even one of the most photographed female entertainers in the world, alongside the likes of Gloria Swanson and Mary Pickford.

But she was also an incredibly brave woman, who used her aptitude for acting to fight injustice worldwide. Baker joined the French Resistance in World War II, for instance, working as a spy to help undermine the Nazi occupation forces that inhabited Paris after the Battle of France. She constantly heard German officers talk about military secrets during her performances and she subsequently passed along the information to Allied operatives within the city. At great peril to her own safety, Baker scribbled everything she heard on the back of music sheets with invisible ink. Baker also emerged as a vocal opponent to racial segregation in the United States, as well, returning to fight the system once the Second World War had ended. With her newfound star power, Baker often forced club owners to desegregate their audiences by refusing to perform in their venues if such a policy remained in place. Her vocal opposition soon earned her the praise of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), making her one of the central figures to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, she was even one of the few people allowed to speak at the famous March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.

Baker continued to perform on stage for the rest of her life, hosting shows at such renowned facilities like the illustrious Carnegie Hall in New York City. But unlike earlier in her career, Baker received great praise from the crowds of an increasingly desegregated American society. When the audience at Carnegie Hall gave her a huge welcome, she wept on stage. Her final show occurred in April of 1975 at the Bobino Theater in Paris. A tribute to her career, the show featured a variety of acts that had originally made her a household name at the start of the century. The sold out crows featured many well-known luminaries, too, including the likes of Sophia Loren and Princess Grace Kelly of Monaco. Those in attendance were so stunned by her performance that they gave Baker a standing ovation once the show concluded. Unfortunately, Baker passed away four days later due to a cerebral hemorrhage. Today, Josephine Baker is remembered as being among the most prolific entertainers in French history, as well as a central figure in the international fight for modern equality.