Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Hotel New Grand, which once served as the headquarters for General Douglas MacArthur following the end of World War II.

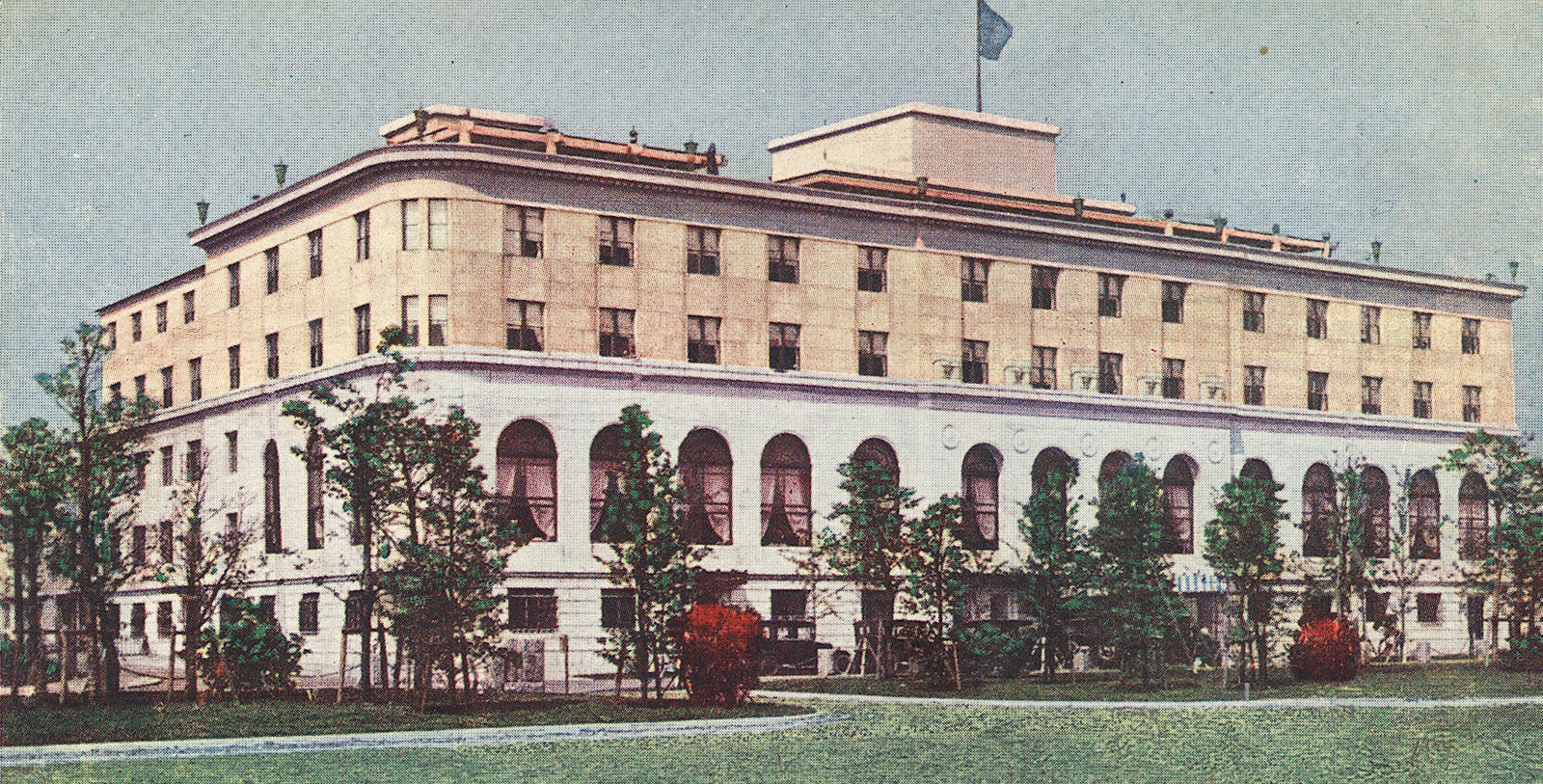

Hotel New Grand, a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2012, dates back to 1927.

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2012, the Hotel New Grand has been among Yokohama’s most enduring symbols over the last century. Chuichi Ariyoshi—(the city’s mayor during the 1920s)—initially created the Hotel New Grand to serve as an avatar of rebirth following the devastation wrought by the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923. The new building immediately became an overnight sensation in Yokohama, offering some of the most upscale accommodations available in the city at the time. It had also developed a considerable reputation for its cuisine, with accomplished Swiss chef Sally Weil serving a stunning array of French-inspired meals from inside its Parisian-themed restaurant. Weil specifically crafted a unique culinary experience at the Hotel New Grand, demonstrating a customer-oriented food service through the execution of both an a la carte and full-course menu. His cuisine proved to be so influential that many of Yokohama residents began emulating his “yoshoku”—or “Western”—dishes.

Over time, the Hotel New Grand’s allure reached an international audience, attracting all kinds of illustrious individuals from throughout the world. Among the famous guests to set foot inside the building included the comedic actor Charlie Chaplin and New York Yankees great Babe Ruth. The future American war hero Douglas MacArthur also visited the hotel during the 1920s, spending his honeymoon on-site while serving under his father, General Arthur MacArthur, in the Philippines. His time at the Hotel New Grand had clearly left an impact, for he returned a decade later as a military advisor to former Filipino president, Manuel L. Quezon. In 1937, he had accompanied Quezon on the latter’s trip to the United States. But on their way back across the Pacific, the party visited Japan and stayed at the Hotel New Grand on the general’s suggestion. MacArthur came back a third and final time some eight years later in his role as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) after World War II. Charged with supervising Japan’s military occupation, MacArthur chose the hotel to function as his first office upon arriving in the country. He specifically set up his administrative headquarters in Room 315 for several months before relocating to the Dai Ichi Life Insurance Building.

The Hotel New Grand subsequently emerged from the Allied occupation of Japan stronger than ever, cementing its legacy as one of Yokohama’s premiere holiday destinations over the next several decades. Popularity remained strong, inspiring its ownership to eventually build a massive extensive called the “Tower Building” in 1991. This magnificent space blended perfectly with the historic, Neoclassical section of the hotel, while also providing 202 new amazing guestrooms. The Hotel New Grand has been lovingly and carefully preserved ever since. Its historical architecture has been continuously restored to its original splendor in order to ensure that future generations will have the opportunity to marvel at the Hotel New Grand. The room that hosted General Douglas MacArthur has even been preserved, functioning today as the prestigious “MacArthur Suite.” In fact, his actual writing desk is still used in the historic space for guests to appreciate and enjoy. Truly few places in Japan are better for a memorable cultural heritage experience than the New Hotel Grand.

-

About the Location +

Yokohama is one of Japan’s youngest cities, for it existed as nothing more than a rural village for millennia. But in 1853, the fate of Yokohama and the rest of Japan changed forever when Commodore Matthew Perry anchored his fleet off the coast of neighboring Kanagawa. President Millard Fillmore had specifically dispatched Perry to forcibly open Japan’s ports to American trade over fears that rival European powers would establish outposts in the archipelago first. Threatened by the commodore’s powerful steamships, the ruling Tokugawa shogunate decided to end the nation’s centuries-long policy of isolation and allowed for the Americans to trade exclusively with a few of its port cities. The relationship was eventually codified via a document known as the “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” some five years later. According the to the original treaty, the major seaport that the Americans were to access was the settlement where Perry had initially come ashore—Kanagawa. But Kanagawa functioned as Japan’s capital at the time, which many in the Tokugawa shogunate wanted to shield from foreign influence. The Japanese subsequently constructed a new port instead, selecting the site of a nearby fishing town to host the new city. Developed a few months later, “Yokohama” quickly became the primary seaport for not just American trade, but all international commerce conducted inside Japan. The city flourished as such, rapidly growing into one of the nation’s largest metropolises by the end of the 19th century. In fact, Yokohama had grown so massive that its borders gradually absorbed many of the surrounding communities, including the once great Kanagawa. Most of the economic activity specifically occurred within a special district called the “Kannai,” which the authorities had enclosed with a moat as a means of controlling the foreigner traders.

Yokohama subsequently endured for decades as one of Japan’s preeminent cities, even after it had ceased functioning as an exclusive treaty port in 1899. And while many products passed through the city’s bustling wharves, it was silk that proved to be its most popular commodity. Foreign entrepreneurs also continued to trade inside Yokohama, with the British emerging as the largest demographic in the years before World War I. Western culture intermingled greatly with local Japanese customs, producing a unique cosmopolitan environment that defined Yokohama for generations. The city’s energetic commercial scene soon attracted the investment of industrialists, who developed hundreds of factories throughout the community. Most of the plants gradually coalesced into part of a famous region known as the “Keihin Industrial Area,” which still fuels the Japanese economy to this very day. But Yokohama’s prosperity was seriously affected by a number of calamities that befell it during the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s. It all began in 1923, when the Great Kantō earthquake destroyed much of downtown Yokohama. Undeterred, the surviving inhabitants quickly rebuilt the city, only for it to be beset by the harsh economic effects of the Great Depression shortly thereafter. Furthermore, American bombers reduced Yokohama back to rubble a decade later during World War II. Fortunately, Yokohama swiftly recovered from the conflict, rebuilding back stronger than ever amid the seven-year-long Allied Occupation of Japan. The city continued to grow for the remainder of the century, amassing a population of some three million citizens by the mid-1980s. To accommodate the enormous influx of new people, local administrators sponsored the creation of a urban development project dubbed “Minato Mirai 21.” Today, Minato Mirai 21 serves as the central business district for modern Yokohama, as well as one of its most exciting cultural centers. The city has emerged as a vibrant tourist destination, as well, due to its many outstanding storefronts, restaurants, and historic sites.

-

About the Architecture +

The historical core of the Hotel New Grand reflects a gorgeous blend of Classical Revival design elements. Also known as “Neoclassical,” Classical Revival architecture itself is among the most common architectural forms seen throughout the world today. This wonderful architectural style first became popular in Paris, specifically among French architectural students that studied in Rome in the late 18th century. Upon their return, the architects began emulating aspects of earlier Baroque design aesthetics into their designs, before finally settling on Greco-Roman examples. Over time, the embrace of Greco-Roman architectural themes spread across the world, reaching destinations like Germany, Spain, Great Britain, and even Japan. As with the equally popular Revivalist styles of the same period, Classical Revival architect found an audience for its more formal nature. It specifically relied on stylistic design elements that incorporated such structural components, like the symmetrical placement of doors and windows, as well as a front porch crowned with a classical pediment. Architects would also install a rounded front portico that possessed a balustraded flat roof. Pilasters and other sculptured ornamentations proliferated throughout the façade of the building, as well. Perhaps the most striking feature of buildings designed with Classical Revival-style architecture were massive columns that displayed some combination of Corinthian, Doric, or Ionic capitals. With its Greco-Roman temple-like form, Classical Revival-style architecture was considered most appropriate for municipal buildings like courthouses, libraries, and schools. But the form found its way into more commercial uses over time, such as banks, department stores, and of course, hotels. Examples of the form can be found throughout many major cities, including London, Paris, and New York City. Architects still rely on Classic Revival architecture when designing new buildings or renovating historic ones, making it among the most ubiquitous architectural styles in the world.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Babe Ruth, famous baseball player for the New York Yankees

Charlie Chaplin, actor known for his silent roles in The Kid and A Woman of Paris.

Douglas MacArthur, general remembered for his campaigns in the Pacific during World War II and the Korean War.