Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Hôtel Molitor Paris - MGallery by Sofitel, which opened in 1929 as the Piscine Molitor Grands Etablissements Balnéaires d’Auteil.

Hôtel Molitor Paris - MGallery by Sofitel, a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2018, dates back to 1929.

VIEW TIMELINEHôtel Molitor Paris - A History

Dive into the history and heritage of the Hôtel Molitor Paris.

WATCH NOWThe Hôtel Molitor Paris – MGallery by Sofitel first opened in 1929 as the Piscine Molitor Grands Etablissements Balnéaires d'Auteuil, a Parisian bathhouse designed by architect Lucien Pollet. The bathhouse was best known for its indoor and outdoor swimming pools, as well as its avant-garde Art Deco décor. For the next 60 years, the complex was Paris's favorite bathhouse and sports complex, where Parisians would come to swim, socialize, and play golf. As the location evolved, the structure quickly became a premium venue for Paris's elite to socialize and host events. Highlights over the years included the 1932 artists’ gala and the annual Fête de l'Eau, which was the pool’s beauty contest. Socialites often frequented the restaurants, tobacco shops, and salons that surrounded the pool. In the 1970s, the bathhouse’s winter pool was replaced with an indoor ice-skating rink. After its installation, the ice rink was only operated for 5 months before its financial burden ultimately led to the closing of the Molitor in 1989, at which point the keys to the building were handed back to the city council. After the complex closed, the building was designated as a historic Parisian building, even though it was considered abandoned.

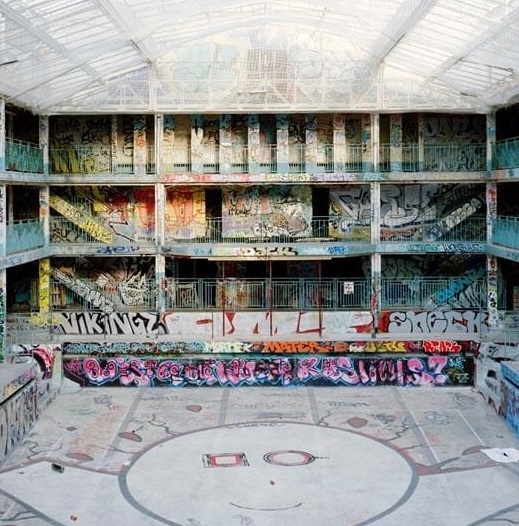

From 1989 to 2014, the building would become a clandestine gathering place for artists, who would bring new life to the building with graffiti art. With the influx of design and color, many photographers began to immortalize the works of now-famed artists, including Reso, Shaka, Katre, Kashink, and Jace. In 2007, the Paris City Council awarded a contract to Colony Capital to restore the building and preserve its historic identity, which lead to the beginning of restorations to transform the location into a hotel in 2011. Unfortunately, much of the historic building was lost due to erosion from chlorine in the pool. However, those areas that could not be saved were restored as closely as possible to their original look. As part of the restoration of the hotel, most of the graffiti was preserved near the pool, the hotel lobby, and other corners of the building for guests to discover. After the restoration was completed, the hotel opened its doors in 2014 as the “Hôtel Molitor Paris - MGallery by Sofitel.” Now one of the best hotels in AccorHotels’ portfolio, the Hôtel Molitor Paris - MGallery by Sofitel was inducted into Historic Hotels Worldwide in 2018.

-

About the Location +

Known as the “City of Lights,” Paris is one of the most famous metropolises in the entire world. Its history harkens back centuries, beginning with the arrival of the Celtic Parisii nearly two millennia ago. They specifically settled around a small island within the Seine that later would be called the “Île de la Cité.” Over time, the small Parisii community emerged as one of the major trading hubs in the region, entertaining merchants from places as far south as the Iberian Peninsula. Its prosperity eventually attracted the attention of the Roman Empire, though, which had been conquering the area of modern-day France amid a conflict known to history as the “Gallic Wars.” Once the Romans subjugated the Parisii in the 1st century BC, they immediately began to redevelop the entire area. They subsequently constructed a much larger settlement that they christened as “Lutetia Parisiorum,” which literally meant “Lutetia of the Parisii.” But unlike the earlier Celtic town, the new Roman city gradually concentrated along the Seine’s left bank. Nevertheless, great wealth continued to flow into the community, leading to a massive wave of construction that expanded its size exponentially. Dozens of magnificent structures quickly dominated the local skyline, including several theaters, temples, baths, and storefronts. Lutetia even entertained a sprawling forum and a spacious amphitheater. (Christianity also arrived in the region, too, with the semi-mythical Saint Davis functioning as its first official bishop during the 3rd century AD.)

But Lutetia’s golden years came to an end when the Roman Empire gradually collapsed throughout the 4th century. Now known exclusively by the name “Parisius,” it soon fell prey to roving bands of Huns—and later Vikings—who prowled across Western Europe with the absence of Roman influence. A group of Germanic people known as the Franks eventually asserted their dominance, who were led by a mighty nobleman named “Clovis.” Clovis’ descendants—known as the “Merovingians”—managed to finally reintroduce some stability, ruling over much of France from Parisius until their successors—the “Carolingians”—relocated the capital to Aachen. The city and its surrounding environs soon reverted to the status of a medieval “county,” which struggled to protect itself from raiders traveling along the Seine. Thankfully, the community was finally spared when one of its ruling counts, Odo, fought off the Vikings once and for all during the Siege of Paris in the late 9th century. (Odo and his line of Robertians would briefly rule over France afterward.) Yet, the city—known by this point as “Paris”—did not truly return to political and cultural relevance until the election of Hugh Capet as French monarch in 987. His own royal dynasty would subsequently rule over France for the next four centuries, with two cadet branches—the Valois and the Bourbons—succeeding it for another five.

Under the Capetians and their successors, Paris reemerged as the cultural capital of France. The monarchs helped directly spawn its rapid growth, commissioning the dredging of the Seine’s right bank for the creation of new neighborhoods. In fact, a whole new massive marketplace debuted in Paris (Les Halles), which subsequently replaced the smaller, older one situated at the Île de la Cité. Still, the Île de la Cité remained the essential “heart” of the city, serving as the site of both the famous Notre-Dame Cathedral and the royal palace, the “Palais de la Cité.” Furthermore, the city quickly became protected by a massive fortress called the “Louvre,” which guarded against foreign military excursions at the height of the Hundred Years War. Yet, despite the imposing defenses that resided within Paris, armies led by the rival Burgundians and English captured the city in the first half of the 15th century. But once the English and their allies were finally defeated in 1453, Paris reverted back to its role as the bastion of the French monarchy. French kings continued to expand upon the city greatly, focusing more on its appearance rather than its military significance. Grander buildings subsequently opened in Paris, including the famed Pont Neuf, the Places des Vosges, and an extension of the Louvre called the “Tuileries Palace.”

Paris once again ceased functioning as the official French capital when King Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” moved his entire court to the Palace of Versailles just beyond the city limits. Still, Paris remained culturally significant, with all kinds of institutions devoted to the arts and sciences debuting inside it. The city, thus, became one of the major intellectual centers for the Enlightenment, as many authors, scientists, and philosophers quickly called the destination home. More beautiful buildings opened as such, including the Place Vendôme, the Places des Victories, and Les Invalides. Even the Champs-Élysées—the main thoroughfare through Paris—underwent a dramatic renovation, as all kinds of gorgeous mansions and shrubbery lined the road. But France began to suffer from a prolonged economic crisis that fanned the flames of discontent toward the French crown. As such, Paris was the epicenter for the French Revolution when it finally erupted in 1789. King Louis XVI and his family were then brought to the city, where they were tried as traitors and executed at the height of the revolution’s Reign of Terror. After a decade of continued political instability, Napoleon Bonaparte—a successful revolutionary general from Corsica—seized power as First Consul, and then Emperor. And while Napoleon fought a series of wars of conquest across Europe, he also proceeded to fully restore Paris back to the capital of France. He specifically bestowed it with his royal patronage that led to a new wave of construction throughout the city. As such, he constructed dozens of new iconic landmarks, like the Arc de Triomphe, the Canal de l’Ourcq, and the Pont des Arts.

Paris continued to permanently act as the official French capital, even after Napoleon’s final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Yet, the city truly began to take on its current appearance and prestige during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte III, who had risen to power in the wake of the tumultuous Revolutions of 1848. Selecting a French official named Georges-Eugène Haussmann, he commissioned a massive building project that sought to transform downtown Paris into what he considered to be a “modern” western city. Its greatest legacy were the buildings that Haussmann constructed, which displayed his patented “Second Empire” architecture. (It is this architectural style that mainly defines Paris’ cityscape to this very day!) Paris continued to endure as a beacon of French—and Western—culture for decades thereafter, even when it was periodically beset by war during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It hosted two magnificent international expositions, such as the 1889 Universal Exposition and the 1900 Universal Exposition, which further solidified Paris’ emerging status as Europe’s cultural capital. (The Eiffel Tower—Paris’ most iconic landmark—debuted the central attraction to one of those fairs.) Many intellectuals from around Europe also continued to move to Paris, too, making it the birthplace of such artistic movements like “Naturalism,” “Impressionism,” “Cubism,” and many other art forms. Paris today still embraces its place in the world as a purveyor of culture, countless museums, art galleries, and theaters attracting thousands of visitors each year. Its historic downtown—centered around the Île de la Cité—have even been designated as one of the most prolific UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Truly few places are better throughout the world for a wonderful, cultural heritage experience that the magnificent “City of Lights.”

-

About the Architecture +

When Lucien Pollet first designed the Piscine Molitor Grands Etablissements Balnéaires d’Auteil, he chose Art Deco architecture as the source of his inspiration. Art Deco architecture itself is among the most famous architectural styles around today. The form originally emerged from a desire from architects to break with past precedents to find architectural inspiration from historical examples. Instead, professionals within the field aspired to forge their own design principles. More importantly, they hoped that their ideas would better reflect the technological advances of the modern age. As such, historians today often consider Art Deco to be a part of the much wider proliferation of cultural “Modernism” that first appeared at the dawn of the 20th century. Art Deco as a style first became popular in 1922, when Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen submitted the first blueprints to feature the form for contest to develop the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune. While his concepts did not win over the judges, they were widely publicized, nonetheless. Architects in both North America and Europe soon raced to copy his format in their own unique ways, giving birth to modern Art Deco architecture. The international embrace of Art Deco had risen so quickly that it was the central theme of the renowned Exposition des Art Decoratifs in Paris a few years later. Architects the world over fell in love with Art Deco’s sleek, linear appearance defined by a series of sharp setbacks. They also adored its geometric decorations that featured motifs like chevrons and zigzags. But despite the deep admiration people felt toward Art Deco, interest in the style gradually dissipated throughout the mid-20th century.