Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover The Union Station Nashville Yards, which was once a grand train hub where notorious gangster Al Capone once passed through.

The Union Station Nashville Yards, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2015, dates back to 1900.

VIEW TIMELINEUnion Station | Memories of Downtown Nashville | Nashville Public Television

Once a working train station and an integral part of the nation's railway system, Union Station in downtown Nashville remains a destination for hotel guests seeking glamor and majesty. In this segment from NPT's popular documentary MEMORIES OF DOWNTOWN NASHVILLE, viewers are taken for a ride through the history of the Nashville landmark.

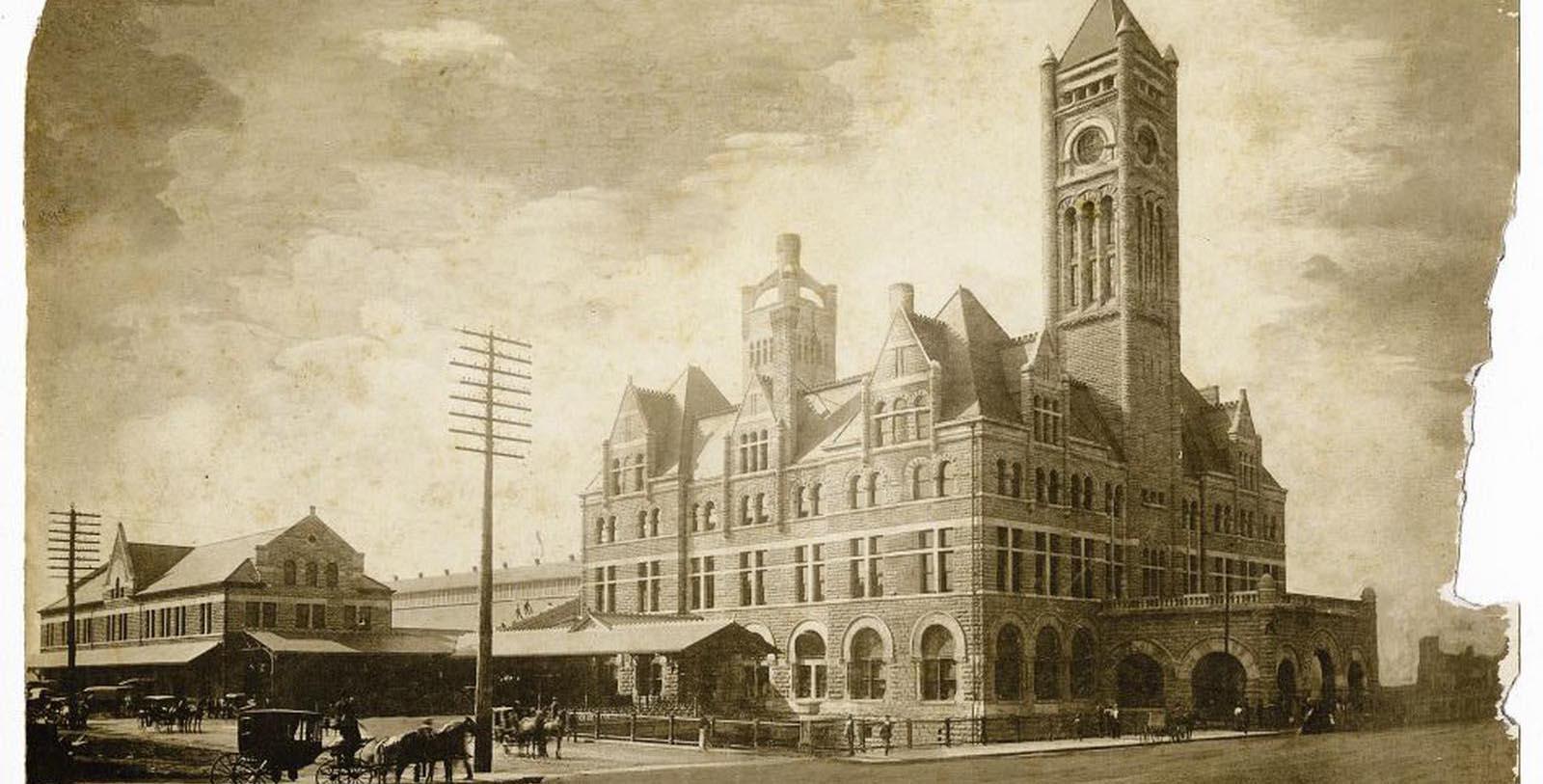

WATCH NOWListed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, The Union Station Nashville Yards has been a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2015. This magnificent building first appeared over a century ago, when travel by rail was at its most popular. One place where passenger trains were incredibly active was the city of Nashville, which had begun to transform into a modern metropolis over the past few decades. To cater to the ever-increasing numbers of guests who used trains to reach the community, the Louisville & Nashville Railroad decided to create a brand-new station downtown. Turning to one of its engineers—Richard Montfort—the company hoped the facility would enchant all who entered Nashville. Construction on the rail station started in earnest in the last 1890s, although it took Montfort several years before he finally created plans to his liking. Amazingly, Montfort had no real training in architecture, only obtaining an engineering degree from the Royal College of Science in Dublin, Ireland, during his youth. Nevertheless, Montfort managed to build a stunningly magnificent structure that quickly became one of the most defining buildings in all of Nashville. The station’s brilliant Romanesque Revival-style architecture was what caused it to stand out, with its high towers and turrets making it an incredibly remarkable sight. Perhaps its most striking feature was its main waiting room, which contained marble floors, beautiful wall accents, and an opulent skylight in the center of its circular ceiling.

Nashville's “Union Station” opened to the public on October 9, 1900. Within a matter of months, the train station soon emerged as one of the busiest in America. Hundreds of people passed through each day, making Union Station resemble something like a bustling beehive. Indeed, some of the most famous people of the day visited at one point or another, including the iconic movie actress Mae West. Federal agents also escorted the notorious gangster Al Capone trough Union Station, who were in the midst of transporting him to the U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta. And hundreds of servicemen and women bought a ticket at Union Station throughout World War II, as the building essentially acted as a major waypoint for those destined to fight in campaigns overseas. Unfortunately, the station fell into disrepair once passenger trains fell out of fashion during the 1960s. Train service was ultimately discontinued in 1979 and the building was completely abandoned. Thankfully, the erstwhile train station finally received a new lease on life after a group of investors acquired the location a decade later. Intent on preserving the station’s historical character, they proceeded to renovate it into a wonderful holiday destination called the “Union Station Hotel.” Work on the Union Station Hotel finally concluded in 1986 and it opened before the public to thunderous applause. Now known as “The Union Station Nashville Yards,” this amazing historic hotel remains one of the most popular places to stay in all of Nashville today.

-

About the Location +

Centuries before the first white settlers crossed the Appalachian Mountains, several famous Native American tribes had passed through the area. Indians such as the Cherokee, the Chickasaw, and the Shawnee all occupied the local banks of the Cumberland River at different points in time. French-Canadian fur traders then eventually traveled to the region in the 1710s, establishing a remote outpost that they named “French Lick.” (Not to be confused with French Lick, Indiana). Settlement by individuals of European origin remained sparse until the eve of the American Revolution, when a North Carolinian jurist named Richard Henderson formally acquired most of the locale in 1775. He had specifically been given the territory from the Cherokee through the historic Transylvania Purchase. While Henderson never lived in the area, he largely directed its inhabitation. Four years after obtaining the land, Henderson sent a party led by James Robertson to investigate the space bordering both sides of the river. Camping in French Lick, they were soon reinforced by another group under the direction of John Donelson. Together, the settlers cleared the wilderness around the outpost and erected a log stockade that they called “Fort Nashborough.” They derived its name from General Francis Nash, who had led the famous 1st North Carolina Regiment during the American Revolutionary War. Mortally wounded at the Battle of Germantown, Nash had since become a national symbol for the Patriot cause.

Over time, a small community formed around the wooden fortress. To maintain order among the village’s population, Richard Henderson created the Cumberland Compact—the first articles of self-governance used to administer the community. At the time of its passing, Fort Nashborough was actually a part of North Carolina. But when nearby pioneers in the mountains failed to create the separate State of Franklin, North Carolina decided to surrender its Trans-Appalachian domain to the federal government. As such, Fort Nashborough became a part of the Territory of Tennessee, which formally joined the Union as a state in 1796. The state legislature subsequently charted the community as the “City of Nashville” approximately a decade later. Nashville quickly emerged as the economic and political hub for the middle of Tennessee. It specifically morphed into a vibrant river trading port, as well as an industrious manufacturing center. Railroads further augmented its prosperity, as it allowed more goods and laborers to flow easily into the city. Plantations fueled by slave labor surrounded Nashville, as well, which primarily grew staple crops like cotton and tobacco. Some of those estates grew to be very large, including U.S. President Andrew Jackson’s plantation “The Hermitage.” As such, Nashville had become Tennessee’s most important community by the mid-19th century. The Tennessee General Assembly even selected the city to serve as the state’s capitol in 1843. It then hired architect William Strickland to design the new state capitol building, which is still in use today!

Nashville’s socioeconomic importance to Tennessee made it a primary target for Union armies when the state sided with the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Occupied in February of 1862 by northern troops, Nashville was the first Confederate capital captured in the conflict. The Tennessee General Assembly and the state governor—Isham G. Harris—quickly fled the city for Memphis. Afterward, President Abraham Lincoln used Nashville as the headquarters for his representatives in the state, specifically Military Governor Andrew Johnson. Nevertheless, rebel guerillas continuously harried the federal soldiers inside Nashville, harassing their lines of supply and communication. The culmination of the Confederate attacks around the city culminated at the end of 1864 with the Battle of Nashville. The climax of the brief—yet fierce—Franklin—Nashville Campaign, the fight was a desperate bid by the rebels to disrupt Union logistics in the Deep South. After chasing its enemy for months, the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Lieutenant General John B. Hood seemingly pinned Major General George H. Thomas’ combined Union force in Nashville. Hoping to lure the federals out of their fortifications, Hood’s men patiently waited outside the city for close to two weeks. On December 15, the Union garrison finally struck, assailing both flanks of the Confederate line. While Thomas’ diversionary assault on the right flank proved to be ineffective, the main thrust against the left shattered the rebel line in a torrent of brutal hand-to-hand fighting. Hood withdrew a few miles to the south that night, with Thomas in hot pursuit. When fighting resumed the following day, the northern soldiers completely routed Hood’s Army of Tennessee.

The end of the Civil War brought about the collapse of slavery and the antebellum economic system that had kept it afloat. Despite enjoying a brief period of freedom in the immediate wake of the conflict, African Americans in Nashville endured racial discrimination that barred them from receiving equal citizenship rights. Known as “Jim Crow,” the laws lasted for decades until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s overthrew them. The city itself was at the forefront of the fight to confront racial segregation, with hundreds of local activists demonstrating across the city. Celebrated today as the “Nashville Sit-ins,’ they largely protested to desegregate businesses in Nashville. Some of the activists—including the late John Lewis—went on the form the historic Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee shortly thereafter. Nashville also grew exponentially as a city, thanks in large part to the popularity of its river wharves and train depots. Thousands of people subsequently moved to Nashville. Dozens of new educational institutions opened in the city, too, reinforcing Nashville’s moniker as the “Athens of the South.” One such facility to open was the great Vanderbilt University. Founded in 1873 thanks to the financing of railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, the university has since grown into a massive, internationally recognized research institute. Another prolific school founded at the time was Fisk University, which became one of the most prestigious black institutions of higher education in the nation. Nashville’s economy continued to expand and diversify, with the fields of agriculture and manufacturing serving as the major local industries. The city specifically became a hotbed for the production of water heaters, appliances, and automobiles in the 20th century. As the decades progressed, though, education, finance, and health care emerged with equal importance to Nashville’s modern economy.

Music soon became Nashville’s most important export. Starting with the regular live broadcasts of the Grand Ole Opry in 1925, Nashville underwent a rapid transformation into the “Music City” that many know and love today. Country music, in particular, became part of the city’s cultural identity, as people across America equated Nashville with the Grand Ole Opry and its stars. Originally hosted from within the Ryman Auditorium, countless country music legends performed on the show at one point or another. Among the famous musicians to sing at the Grand Ole Opry included Gene Autry, Bill Monroe, Ernest Tubb, Roy Acuff, and Hank Williams. (Many of those individuals even stayed at The Hermitage Hotel!) The national infatuation with the Grand Ole Opry—and country music in general—exploded in the decades following World War II, giving rise to the commercialization of the genre as a whole. Many new prolific record labels flourished in Nashville as a result, such as the likes of Mercury, Capitol Records, and RCA. Concentrated in an area of town called “Music Row,” those recording studios—primarily RCA’s Studio B—were largely responsible for creating a sub-type of country music known as the “Nashville Sound.” New generations of musicians also started flocking to the city in search of an opportunity to make a name for themselves. Among the performers to arrive in Nashville included the likes of Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn, Patsy Cline, Charley Pride, Tammy Wynette, and Buck Owens. Country music has since become one of the most beloved cultural art forms in the United States. It is celebrated all over Nashville today, particularly in the world-renowned Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. No trip to Nashville is complete without a visit to this fascinating institution.

-

About the Architecture +

The Union Station Nashville Yards shows some of the finest elements of Romanesque Revival architecture. Romanesque Revival-style architecture is a wonderful architectural style that first appeared in North America in the middle of the 19th century, as design principles from both Rome and medieval Europe found a popular audience. Architects interested in specializing in Romanesque Revival-themed architecture specifically studied the works of Norman and Lombard engineers who were active in the 11th and 12th centuries. Structures created with the aesthetic are commonly defined by their pronounced round arches and round towers. Yet, those grand archways and towers were far less ostentatious than their historic counterparts located on the other side of the Atlantic. Romanesque Revival-style architecture also implemented squat columns, decorative wall carvings, and the extensive use of masonry. But architects would sometimes favor wood over bricks or stones due to financial concerns. The first wave of Romanesque Revival-style architecture impacted North America in the 1840s and 1850s, appearing in such cities as Washington, D.C., and Toronto. University College at the greater University of Toronto is one such example of a brilliant Romanesque Revival-inspired structure to emerge at the time. But the general public in both the United States and Canada did not fully embrace the aesthetic, preferring the tastes of Italianate and Gothic Revival architecture at the time. It was not until an American architect named Henry Hobson Richardson started using the form in the late 1800s that Romanesque Revival style finally became popular. A graduate from the renowned École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Richardson developed numerous designs in places like New York City, Boston, and Detroit. His approach to Romanesque Revival style was somewhat different, as it also incorporated elements of medieval Mediterranean design principles. His vision of Romanesque Revival-style architecture was soon embraced by other architects, including those in neighboring Canada. Historians today largely refer to Richardson’s design philosophy as “Richardson Romanesque” architecture.

Guest Historian Series

Read Guest Historian SeriesNobody Asked Me, But... No. 232;

Hotel History: The Union Station Nashville Yards (1900), Nashville, Tennessee*

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Long before it was a historic hotel, the Nashville, Tennessee Union Station was a key center in America's economy and transportation. Opening on Oct. 9, 1900, for the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, the building's imposing Gothic design featuring a soaring barrel-vaulted ceiling and Tiffany-styled stained glass, was a testament to U.S. ingenuity and energy. During railroading's glory years, Mafia kingpin Al Capone was escorted through here on his way to the Georgia penitentiary. Other fascinating facts surrounding this historic Nashville station include:

- Construction began on August 1, 1898

- Station officially opened on Oct. 9, 1900

- The track level once held two alligator ponds

The Train Shed was the largest unsupported span in America, housing up to 10 full trains at once

Pulsing locomotives hissed on the platforms, as gravel-throated conductors shouted, "All aboard!" The stunning Union Station Nashville Yards is truly special for the following characteristics:

- Heavy-stone Richardsonian-Romanesque design

- Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977

- Sixty-five foot, barrel-vaulted lobby ceiling, featuring gold-leaf medallions, and 100-year-old original Luminous Prism stained glass

- Marble floors, oak-accented doors and walls, and three limestone fireplaces

- Twenty gold-accented bas-relief angel of commerce figurines

- Two bas-relief panels—a steam locomotive and horse-drawn chariot ̶ at each end of the lobby

Union Station was designed by one of the most famous American architects: Henry Hobson Richardson who, along with Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright was one of "the recognized trinity of American architecture." Of the ten buildings named by American architects as the best in 1885, fully half were his: Trinity Church in Boston, Albany City Hall, Sever Hall at Harvard University, the New York State Capital in Albany (as a collaboration), and Town Hall in North Easton, Massachusetts. Richardson designed nine railroad stations for the Boston & Albany Railroad as well as three stations for other lines including The Union Station Nashville Yards for the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.

The station reached peak usage during World War II when it was the shipping-out point for tens of thousands of U.S. troops. After the war, it started a long decline as passenger rail service in the U.S. generally was reduced. By the 1960s, it was served by only a few trains daily. Much of its open spaces were roped off and its architectural features became largely the habitat of pigeons. The formation of Amtrak in 1971 reduced service to the northbound and southbound Floridian train each day. When this service was discontinued in October 1979, the station was abandoned entirely. The station fell into the custody of the United States Government's General Services Administration. In the early 1980s a group of investors came forward with a plan to finance the renovation of the station into a luxury hotel which was approved. After extensive renovation, the new investor group who bought the hotel out of bankruptcy were able to operate it profitably.

By the mid-1990s they had restored Mercury to his place atop the tower, albeit in a two-dimensional form painted in trompe l'oeil style to replicate the original. This was destroyed in the 1998 downtown Nashville tornado but was soon replaced.

Frommer's Review reported in The New York Times:

"Built in 1900 and housed in the Romanesque Gothic former Union Station railway terminal, this hotel is a grandly restored National Historic Landmark. Following a $10-million renovation, completed in 2007, all guest rooms and public spaces have been updated. The lobby is the former main hall of the railway station and has a vaulted ceiling of Tiffany stained glass [...]."

*excerpted from his book Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.