Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

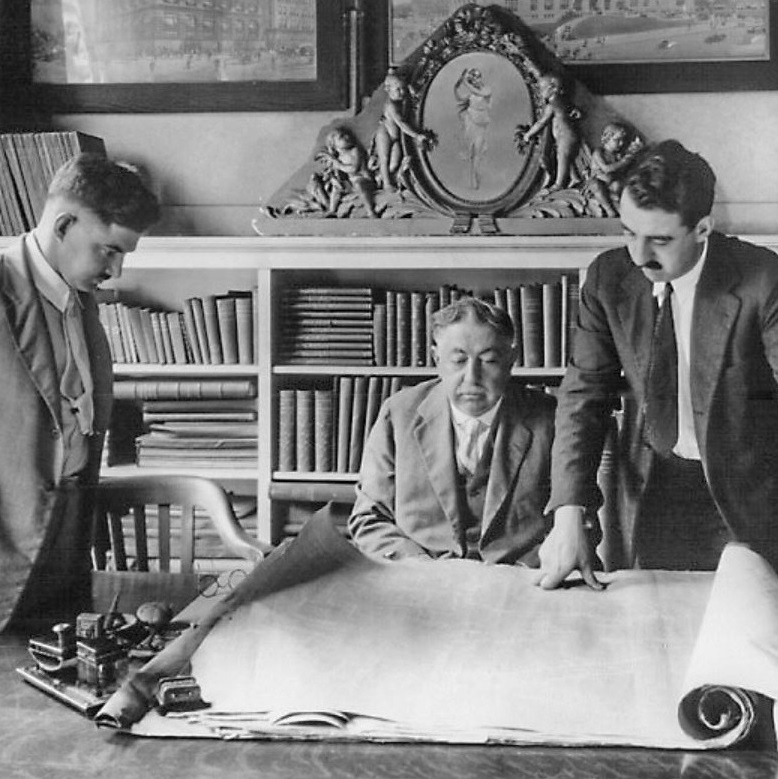

Discover The Peregrine Omaha Downtown, Curio Collection by Hilton, which was originally designed by the renowned architect John L. Latenser.

The Peregrine Omaha Downtown, Curio Collection by Hilton—a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2022—dates back to 1912.

VIEW TIMELINEAn Omaha Designated Historic Landmark, The Peregrine Omaha Downtown, Curio Collection by Hilton has been a cherished local landmark for more than a century. Indeed, the building’s gorgeous façade has been an iconic sight for travelers making their way down Omaha’s Grand Army of the Republic Highway for generations. Its origins specifically harken back to two local entrepreneurs from the early 20th century—John Kennedy and Charles Saunders. (Saunders was the son of Nebraska governor Alvin Saunders.) Seeking to capitalize upon the economic boom spreading across Omaha at the time, the two men wished to develop their own complex that they could rent to commercial tenants. To that end, they selected a plot of land next to the gorgeous Brandis Theater, which had just opened in 1910. Impressed with its architectural appearance, Kennedy and Saunders hired its architect—John L. Latenser—to oversee their building’s creation. Working alongside the firm Selden Breck Construction, Latenser proceeded to raise a stunning multistory edifice that was hailed as one of the most beautiful buildings in the whole city. Latenser subsequently used the neighboring Brandeis Theater as the primary source of his inspiration, which he eventually connected to the office building! Nevertheless, the new Saunders-Kennedy Building—as it was called—featured its own unique characteristics, namely elements of Renaissance Revivalism that appearead on the façade.

When construction on the structure concluded right before World War I, the magnificent Saunders-Kennedy Building became an immediate icon for downtown Omaha. The building measured as the largest commercial structure of its kind in the city, covering the entire northern half of its block! The Saunders-Kennedy Building remained a fixture in Omaha for years, even after the Brandeis Theater was demolished during the 1950s. Then in 1987, a local Omaha company known as the “Woodmen of the World Life Insurance Society” purchased the structure to serve as its headquarters. (The company specifically acquired the building because it operated at another location—the Woodmen Tower—right next door.) But once the business left the premises a few years later, the fate of the Saunders-Kennedy Building seemed uncertain. Thankfully, salvation arrived once Clarity Development Group and ViaNova Development teamed up to thoroughly renovate the site into a spectacular boutique hotel. Work began in 2017 and lasted for several years. The restoration managed to brilliantly transform the building’s interior layout during that period while preserving much of its fantastic historical architecture. After months of constant construction, the reborn Saunders-Kennedy Building finally debuted as “The Peregrine Omaha Downtown, Curio Collection by Hilton” in 2021. It has since emerged as one of the best places to stay in Omaha.

-

About the Location +

Native Americans were the first to inhabit the region, specifically the Omaha people, from which the modern city got its name. But upon the arrival of Euro-American settlers in the early 19th century, the Omaha and other indigenous people gradually vacated the area through a series of treaties with the federal government. The last of their land was ceded to the United States by the middle of the century, helping prompt Congress to pass the controversial Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Among the many changes the legislation implemented was opening the Nebraska Territory to widespread settlement. As such, a group of entrepreneurial residents from Council Bluffs, Iowa, decided to create a city right across the Missouri River. They hoped the new community would serve as the capital for the Nebraska Territory, which, in turn, would convince politicians in Washington to direct a prospective transcontinental railroad through both towns. Selecting the site of a former Mormon camp known as “Winter Quarter,” the civic leaders immediately set about establishing the initial street grid for Omaha. Within months, hundreds of people had forded the river to obtain a plot of land within the budding community. In fact, by the eve of the American Civil War, Omaha had well over a thousand people living inside its borders. A big reason driving the early growth was the city’s proximity to the Platte Valley, one of the most accessible routes for settlers to cross while heading farther west. Many who moved into Omaha subsequently opened businesses that catered to the many wagon trains that had begun to arrive on their way into the valley.

Omaha’s prosperity inspired the territorial legislature to recognize it as the region’s capital, although it later lost that designation once Nebraska was admitted as a state in 1867. Nevertheless, its brief time as the capital convinced the federal government to direct the Union Pacific Railroad to lay track through the area. (President Abraham Lincoln even designated Omaha as the eastern terminus for the rail line.) The arrival of the Union Pacific Railroad and several others further galvanized Omaha’s fledgling economy. Indeed, its emergence as an important regional transportation hub incentivized many companies to open factories and warehouses throughout the city. Despite enduring a short-lived depression at the end of the century, Omaha became an important center for industries like smelting and wholesaling. Meatpacking became very prominent, especially once the historic Union Stock Yards opened in South Omaha during the 1880s. As a means of celebrating the city’s regional significance, many of its leaders even arranged to organize the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in 1898. (Omaha also hosted the prestigious Indian Congress around the same time.)The tremendous economic activity also attracted more people from across the United States, including African Americans from the Deep South. Those numbers were augmented by thousands of European immigrants from Poland, Germany, and Italy. The population thus swelled to an incredible size, with some 102,000 living in Omaha at the start of the 1900s.

Omaha remained an essential city in the western United States well into the 20th century, largely thanks to its robust local economy. World War II played an integral role in maintaining Omaha’s economic clout, spawning the Glenn L. Martin Bomber Plant and the Offutt Air Force Base. (While the Glenn L. Martin Bomber Plant is no longer open, the Offutt Air Force Base exists today as the home of U.S. Strategic Command.) Omaha became one of the leading national centers in the push to affirm equal rights throughout the country during the 20th century, too. Omaha still maintains its status as a culturally diverse municipality. It continues to be very prosperous, as it still hosts dozens of industries specializing in agriculture, manufacturing, and food processing. The renowned investor Warren Buffett—a native of Omaha—even operates his famous Fortune 500 company, Berkshire Hathaway Inc., in the city. But Omaha is also a popular holiday destination among tourists, including cultural heritage travelers interested in experiencing more about the history of the historical American West. Among the institutions that chronicle Omaha’s intricate past are the Durham Western Heritage Museum, the Great Plains Black Museum, the Old Market District, and the Lewis & Clark Landing. Additional cultural attractions include the Joslyn Art Museum, the Holland Performing Arts Center, and the Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium.

-

About the Architecture +

When John L. Latenser first designed what would become The Peregrine Omaha Downtown, Curio Collection by Hilton, he chose Renaissance Revival-style architecture to help guide his work. Latenser had used his designs for the neighboring Brandeis Theater as the primary source of his inspiration. Still, he settled on Renaissance Revivalism as a way of giving the Saunders-Kennedy Building its own identity. Nevertheless, Renaissance Revival architecture is a group of architectural revival styles dating back to the 19th century. Neither Grecian nor Gothic in their appearance, Renaissance Revival-style architecture drew inspiration from a wide range of structural motifs found throughout Early Modern Western Europe. Architects in France and Italy were the first to embrace the artistic movement, who saw the architectural forms of the European Renaissance as an opportunity to reinvigorate a sense of civic pride throughout their communities. Those intellectuals incorporated the colonnades and low-pitched roofs of Renaissance-era buildings with the specific characteristics of Mannerist and Baroque-themed architecture. Perhaps the most significant structural component of a Renaissance Revival-style building involved the installation of a grand staircase in a vein similar to those located at both the Château de Blois and the Château de Chambord in France’s Loire Valley. This particular feature served as a central focal point for the design, often directing guests to a magnificent lobby or exterior courtyard. But the nebulous nature of Renaissance Revival architecture meant that its appearance varied widely across Europe. Historians today sometimes find it challenging to provide a specific definition for the architectural movement. Regardless, Renaissance Revival architecture today remains one of the world’s most enduring, appearing in countless places across the globe.