Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

wakulla springs lodge history

Discover the Lodge at Wakulla Springs, where stunning natural components, such as marble and heart cypress, are woven into the Florida hotel's exquisite design.

The Lodge at Wakulla Springs, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2016, dates back to 1937.

VIEW TIMELINEEd Ball's Fountain of Youth

Shot in 1951, this film by Edward Ball himself attempted to chronicle the story of Wakulla Springs. Gain a rare glimpse into the mind of a historic hotelier as they describe the verdant landscape of the region.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2016, The Lodge at Wakulla Springs has been one of the iconic landmarks inside the renowned Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. This beautiful historic hotel in Florida can trace its lineage all the way back to Edward Ball, who was one of the most influential people in Florida throughout much of the 20th century. Ball got his start working for his powerful brother-in-law, Alfred I. du Pont, who assigned him manager of the family’s Clean Food Products Company. In private, though, Ball was du Pont’s business advisor and the two developed a close relationship. Thus, when Alfred I. du Pont and his wife, Jessie, moved to Florida from their native Delaware in 1926, Ball followed suit. Alfred eventually died in the mid-1930s, leaving a massive inheritance of $26 million to Edward Ball. Ball also managed Alfred’s estate on Jessie du Pont’s behalf, specifically the Alfred I. du Pont Testamentary Trust. As such, he supervised every financial asset that du Pont had left behind. Ball immediately began to grow his own wealth, as well as that of the trust. Soon enough, he was building an economic empire across the state through his management of such operations like the Florida East Coast Railway, the St. Joe Paper Company, and the Florida National Bank. But Ball also aggressively invested in land around Tallahassee and Pensacola, enlarging the trust’s landholdings to some 1.2 million acres!

Among the smaller economic endeavors that Ball pursued in his lifetime was the creation of The Lodge at Wakulla Springs. Ball had actually spent several years prior to Alfred’s I. du Pont’s death investing in private real estate, buying 4,000 acres of land near Wakulla Springs in 1931. When he first laid eyes upon the area, Ball “knew that the area had to be preserved, but didn’t known exactly how at the time.” But he eventually decided to develop the area into an exclusive holiday destination, hoping that the area’s lush scenery and deep, freshwater spring would attract countless guests. Ball finally put his plan into motion in 1935, using his newfound affluence to finance the construction of a brilliant boutique hotel. He worked diligently alongside a Jacksonville-based architectural firm called “Marsh and Saxelbye” to design the vacation getaway. Opening its doors as “The Lodge at Wakulla Springs” two years later, it immediately became an overnight sensation across the country. Standing two stories tall, the new hotel featured some of the best Mediterranean Revival-style architecture in all of Florida. Ball had specifically constructed the entire building with Tennessee marble and Heart Cypress logs, especially in the Great Lobby. Perhaps the hotel’s most stunning space, it contained a beautiful fresco that reflected a combination of European folk art, intricate Arabic scroll work, and Native American artistic influences.

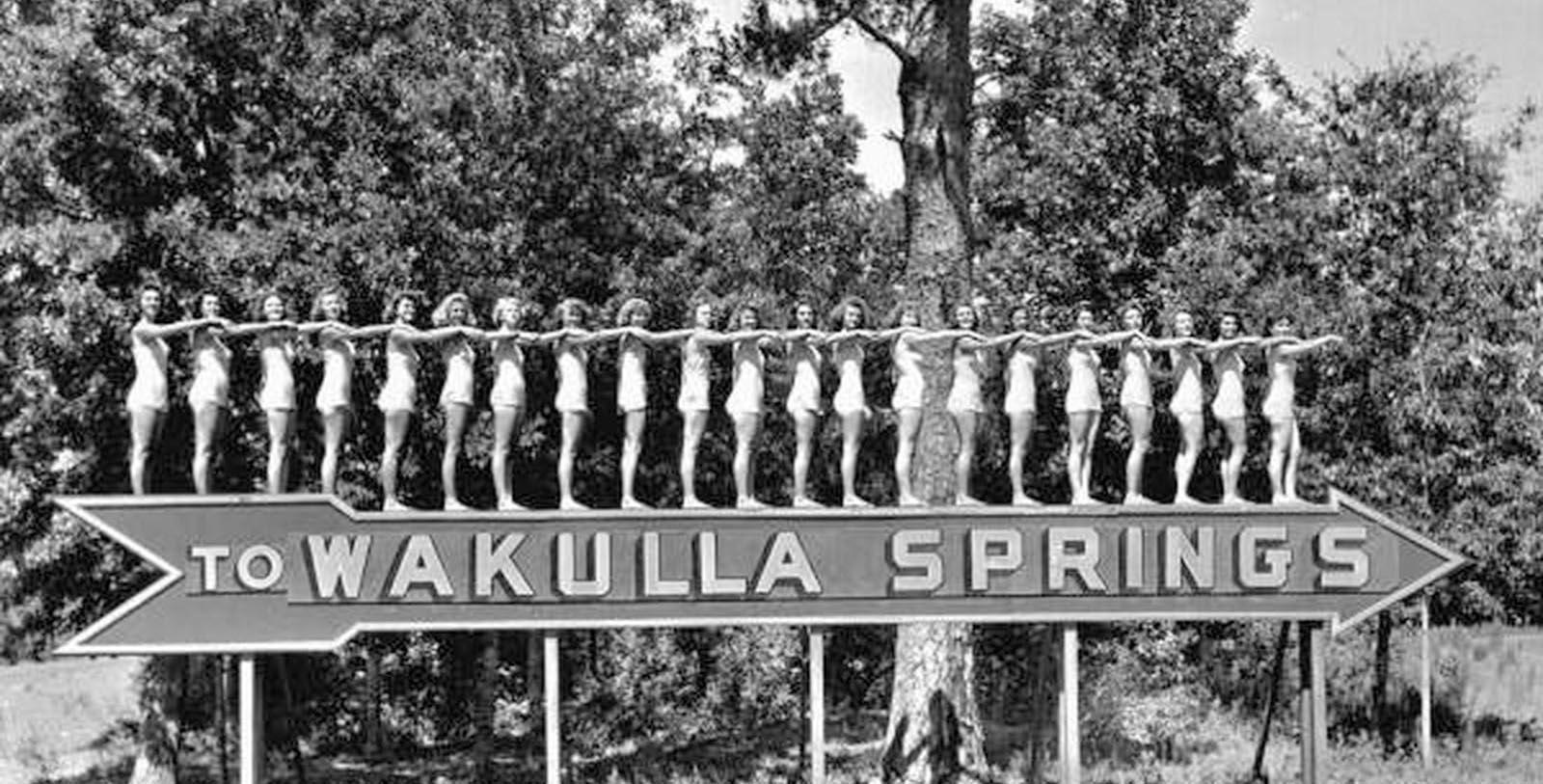

In 1939, Edward Ball made the fateful decision to hire famed swimming coach Newton “Newt” Perry to serve as the hotel’s general manager. The choice would forever change The Lodge at Wakulla Springs. Perry himself was Hollywood insider, having served as a consultant for on-location water scenes for many years. He had specifically pioneered a way to shoot film underwater, too, which inspired many up-and-coming filmmakers to seek his expertise. As such, Perry used his connections in the movie industry to attract all kinds of upscale clientele. Yet, the directors began to use both the hotel and its surroundings as the setting for various films, starting with Richard Thorpe’s Tarzan’s Secret Treasure in 1941. Starring Olympic-class swimmer Johnnie Weismuller, the movie established The Lodge at Wakulla Springs as an amazing place to produce all kinds of films. Eight more movies were shot in the area, including the likes of Amphibious Fighters, Around the World Under the Sea, and Night Moves. Director Jack Arnold also filmed portions of the legendary Creature from the Black Lagoon onsite, too, filming the movie’s tropical scenes in the area of Wakulla Springs. And all of the underwater shots featured in the movie Airport ’77 were staged just beyond the hotel’s front door. The film crew even erected a partial replica of a submerged passenger jet on the grounds!

Toward the end of his life, Edward Ball began donating larges tracts of unused land around The Lodge at Wakulla Springs to Florida State University. The most significant amount of land that he gifted went to the State of Florida itself, which it turned into the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. Ball finally passed away in 1981, leaving the celebrated hotel without an owner for the first time in its venerable history. Fortunately, the Edward Ball Wildlife Foundation acquired the location shortly after his passing and invested heavily into its renovation. It then gave The Lodge at Wakulla Springs over the State of Florida, which included it as an attraction within the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. Then, in 1993, the US. Department of the Interior identified all of the places inside the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park as a National Natural Landmark, including The Lodge at Wakulla Springs. (The agency also declared Wakulla Springs to be a National Historic District two years later, after archaeologists uncovered ancient Paleo-Indian sites throughout the area.) The Lodge at Wakulla Springs has since remained true to Edward Ball’s vision by consciously preserving the land, and focusing on nature conservancy. But it also maintains its original atmosphere of serenity and peace that it had when it first opened nearly a century ago.

-

About the Location +

A U.S. Natural Landmark, the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park is located in the heart of Wakulla County, Florida. Native Americans once lived in the region for thousands of years, occupying remote villages amid the mangroves. The indigenous people were culturally a part of the Upper Paleolithic Indians, having crossed from Asia to North America—possibly by way of the theoretical “Beringia”—at the height of the Pleistocene. Scholars have found all sorts of archeological evidence suggesting their inhabitation of the springs, with Clovis spear points uncovered in large numbers. (The U.S. Department of the Interior has since identified the area as the “Wakulla Springs Archeological and Historic District.) Park officials have ultimately found some 54 different archeological sites throughout Wakulla Springs, including several on the grounds of The Lodge at Wakulla Springs. Yet, the region was also home to many ancient species, including such extinct animals like the saber-toothed tiger, the American lion, the Columbian mammoth, and the American mastodon. In fact, hotelier Edward Ball filmed the discovery of a mastodon’s skeletal remains in one of his promotional films (see above). Geological research in the region did not actually being until 1930, although scattered investigations had been ongoing ever since the middle of the 19th century. Working on behalf of the Florida Geological Survey, geologist Herman Gunter recovered a number of ancient fossil via a technique known as “hard hat diving.” Using a dredge, Gunter and his colleagues managed to extract most of the specimens from the water. One of their greatest finds—a mastodon—was even moved to the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee, where it currently sits on display. Additional scientific investigations into the region’s historic habitat have occurred since then, specifically in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1980s. Wakulla Springs itself is named after a subterranean freshwater well, which is both the largest and deepest in existence. Cave divers today can explore the system for themselves, as its opening cavern is easily accessible to those with underwater breathing equipment. The Edward Ball Wakulla State Park is now among the most popular destinations in Florida. It provides for hours of entertainment, offering a wealth of activities like hiking, snorkeling, swimming, and sightseeing.

-

About the Architecture +

Working alongside Jacksonville-based architectural firm “Marsh and Saxelbye,” Edward Ball designed all aspects of The Lodge at Wakulla Springs. He did everything from outlining the floor plan to the layout of certain rooms. Even though Ball stared creating blueprints for the building during the early 1930s, construction really began in earnest in 1935. He specifically had an eye for quality and durability, demanding that the building would be able to withstand the ages. Nowhere is Bell’s penchant for detail more apparent that in the hotel’s Great Lobby. Fine Tennessee marble and Heart Cypress logs proliferate throughout the space, giving it a brilliantly rustic ambiance. Marble, in particular, is in great abundance, which constitutes the flooring, thresholds, and countertops. A magnificent marble stairwell also resides in the room, too, constructed with massive, face-matched grain panels that were all cut from one block. Its spectacular wrought iron railings were even forged onsite and displays local wildlife—such as limpkins and herons—within its balustrade. Interestingly, the expansive transverse beams that span the ceiling are actually outfitted with cypress planks, while a steel superstructure sits directly behind them. Standing some 16 feet in height, the ceiling itself is incredibly spectacular. Artists painted a stunning mural that reflected a combination of European folk art, intricate Arabic scroll work, and Native American artistic influences. The most recognizable images included involved tropical birds, Spanish galleons, and scenes depicting different aspects of Floridian history. Two paintings of women also flank both sides of the mural, who overlook the lobby’s main entrance. The mural had fallen into such a state of decay that the Friends of Wakulla State Park commissioned Rustin Levenson of the Art Conservation Association to clean it. It ultimately took seven conservationists to reverse the damage. Another iconic component of the lodge is its Art Deco elevator, which is original to the building. The only known working elevator of its kind, its interior is covered in rich walnut, as well as an inlay of various colored woods. As such, The Lodge at Wakulla Springs is truly a sight to behold.

Edward Ball also chose Mediterranean Revival—style themes to build The Lodge at Wakulla Springs. Mediterranean Revival-style architecture itself is a gorgeous—but rather peculiar—structural aesthetic. Popular among American architects at the height of the Roaring Twenties, its main characteristic was its intrinsic eclecticism. While most Revivalist styles typically mimicked one or two earlier architectural forms, Mediterranean Revival-style took its inspiration from several, including Italian Renaissance, Spanish Colonial, and French Beaux-Arts. The amalgamation of so many unique design principles into one singular form was born out of a desire to create exotic buildings that closely resembled the different kinds of historic palaces scattered throughout the Mediterranean basin. As the modern hospitality industry exploded in Florida and California in the 1920s and early 1930s, American architects—as well as the hoteliers who served as their clients—hoped such an appearance would epitomize the tropical atmosphere of their respective states. But they also wished that the new style would significantly impress the throngs of tourists that had started to south and west as a means of escaping the harsh winters of the Northeast. As such, Mediterranean Revival-style architecture was predominantly used to create hotels and resorts, although some affluent Americans began using the form to construct their own personal homes. Architects August Gieger and Addison Mizner were the two most prominent professionals to popularize the style in Florida, while the likes of Bertram Goodhue and Sumner Spaulding used it frequently in California. Mediterranean Revival-style typically relied on a regular, rectangular floorplan that featured grandiose, symmetrical façades. Stucco exterior walls and red-tile roofs were perhaps the greatest structural elements. Yet, American architects also incorporated wrought iron balconies into the overall design, as well as numerous keystones and arched windows with grilles.

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Tarzan’s Secret Treasure (1941)

Tarzan’s New York Adventure (1942)

Amphibious Fighters (1943)

The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954)

Return of the Creature (1956)

Around the World Under the Sea (1966)

Night Moves (1975)

Joe Panther (1976)

Airport ‘77 (1977)