Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

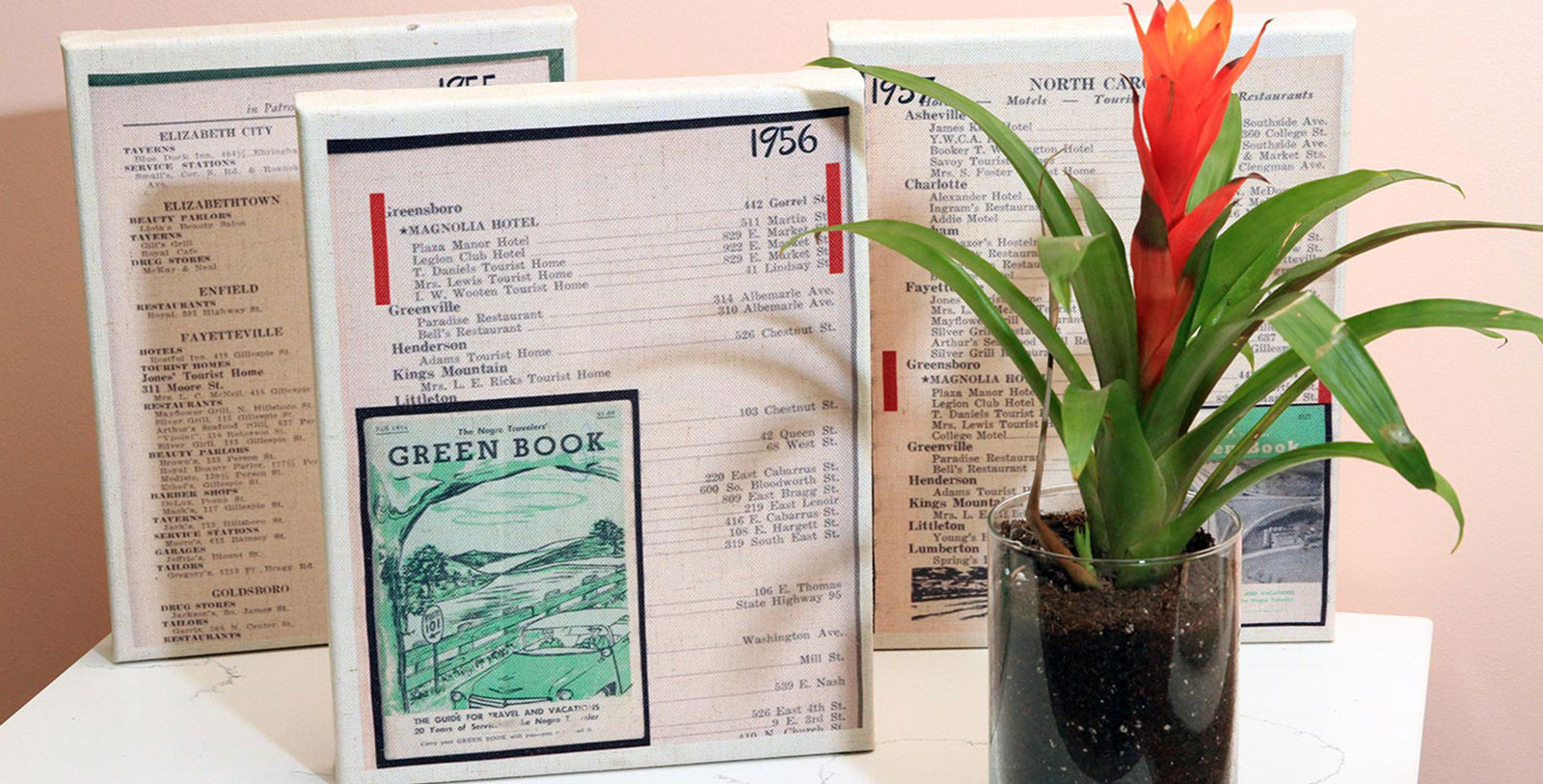

Discover The Historic Magnolia House, which is one of the last surviving hotels to appear in the historic Green Book—a travelers’ guide that detailed businesses that were safe for black patrons to visit during the Jim Crow era.

The Historic Magnolia House, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2022, dates back to 1889.

VIEW TIMELINEThe Historic Magnolia House

Buddy Gist (The Best Friend of Miles Davis) shares his experiences in the only motel African Americans could stay in during Jim Crow Era, as well as the personal stories of the famous guests that stayed here.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2022, The Historic Magnolia House has been a fixture in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina, for more than a century. Indeed, it has even been listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior as a contributing building within the larger South Greensboro Historic District. While the structure originally served as a house at the height of the Gilded Age, its identity as a hotel began after World War II. Housing prices in the area had become affordable for local black families, prompting a rush of real estate investment that lasted for some time. The structure that would become The Historic Magnolia House was among the buildings purchased, specifically by married couple Arthur and Louise Gist in 1949. The two proceeded to transform the home into a quaint, six-bedroom “traveler’s motel” that visiting black travelers could use while passing through Greensboro. Segregation was then institutionalized throughout North Carolina, meaning that most hotels only provided services to white patrons. The Gists thus bravely offered a rare (and even dangerous) service by opening their building to other African Americans. Not long thereafter, the Gist family started introducing their new business annually as the “Magnolia Hotel” in the Negro Motorist Green Book during the mid-1950s. As such, it became one of just a few Greensboro-based businesses to appear in the guide. It ultimately appeared inside the book for a total of six years from 1955 to 1961, save for a brief absence in 1958. The hotel’s name was bolded within nearly all those issues, too, indicating that it wielded a great reputation.

The association only further enhanced its status, as visits to the Magnolia Hotel increased exponentially. Many famous African American figures were soon staying at the hotel, including people like Jackie Robinson, Lena Horne, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Indeed, James Brown would regularly play with neighborhood children on-site, while Joe Tex often signed autographs on the wraparound porch. Ray Charles stayed so much that he could walk the halls despite being blind, and Louis Armstrong was known to adore Louise’s cooking. Miles Davis had even formed a close friendship with the Gist family. In fact, Arthur and Louise’s son, Buddy, occasionally watched Davis’ children whenever he left to go on tour! Some of those guests (namely entertainers) had arrived on their tours along the Chitlin Circuit—a route of musical venues that first began traversing the American South around World War I. Those singers had booked a room in order to play at one of the nearby sites on the trail, such as the El Rocco Club and Carlotta. Nevertheless, the Gists still lodged regular people within the black community. It gained a strong following among ordinary black motorists, especially the families of students attending Bennet College and the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. The Magnolia Hotel accommodated numerous public events as well, such as holiday parties, networking get-togethers, and military reunions. They even hosted meetings for the local branches of various civil rights groups, including the Democratic Club of Guilford County and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

After the Johnson Administration signed The Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law—which made travel and lodging safer for African Americans due to it prohibiting discrimination in places of public accommodation—The Magnolia House lost most of its visitors. It was increasingly more difficult for the Gist family to run the business and it ultimately closed following Arthur’s death in 1979. The erstwhile hotel then sat abandoned for many years thereafter until Sam and Kimberly Pass managed to acquire it during the mid-1990s. Intent on saving its fantastic heritage, the two decided to restore the facility and spent years reconstructing the location. But when the revitalized building debuted as “The Historic Magnolia House” in 2012, it received profound acclaim for the Pass’ masterful preservation of its architectural integrity. Today, the hotel is under the care of Natalie Pass-Miller after a grand reopening in January 2022. Miller created The Historic Magnolia House Foundation two years prior to raise money to save the neighborhood treasure. The work of the foundation does not end with the hotel, and the additional rooms they plan to open after restoring another local historic structure. Natalie, and her parents the Pass’ are planning to open a Museum and Art Center, which will house rare oral histories, special exhibits, and more. The hotel has recently received a grant from American Express and the National Trust for Historic Preservation through the Backing Historic Small Restaurants Grant Program, designed to aid restaurant recovery amid ongoing challenges related to the pandemic. This fantastic historic destination was even previously named by the National Trust for Historic Preservation one of its “Distinctive Destinations.”

-

About the Location +

The Historic Magnolia House is one of the main contributing structures identified as part of the historic South Greensboro Historic District. The district itself is listed in the National Register of Historic Places by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior—a status that it has entertained since 1991. Greensboro itself is among North Carolina’s most historic communities, having first been incorporated centuries ago at the start of the 19th century. In 1808, it had been organized by the descendants of British Quakers, Scotch-Irish pioneers, and German immigrants, who had first settled the region during the mid-18th century. Many of those residents had wished to form a new seat for greater Guildford County, as the original one—Martinville—was considered too far away from most homes. The work to create the city had taken a whole year to complete, with its nucleus emerging in the heart of today’s Fisher Park neighborhood. To christen the new settlement, the residents opted to name it “Greensboro” in honor of General Nathaniel Greene, a revolutionary war hero. Greene himself had fought the British with great skill at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, which had occurred just north of modern Greensboro in 1781. While Greene ultimately lost the contest, the battle inflicted heavy casualties upon the British that forced them to abandon their hold over North Carolina.

In the years following Greensboro’s official incorporation, it quickly emerged as one of the most important metropolitan areas in the state. The arrival of the railroads during the 1850s heralded this transformation, which enabled various entrepreneurs to construct several factories and mills all over town. Nevertheless, the American Civil War abruptly brought an end to this growth, despite the city’s distance from the conflict’s ever-changing frontlines. Greensboro underwent other significant changes at the time, too, with one of the greatest being the emergence of a robust African American community known as “Warnersville” within the town limits. It soon became a haven for the freed slaves that had arrived from the countryside, providing a safe space for shelter and work. Greensboro’s industrialization only returned in the wake of the war, thanks to the fact that the city had not suffered any serious hardships. Indeed, many innovative individuals returned to Greensboro to open a variety of businesses that manufactured everything from furniture to refined tobacco products. One soon-to-be famous enterprise was Lunsford Richardson’s Vick Chemical Company, which produced famous cold remedies for generations. But none of them matched the importance of the city’s teeming textile mills that soon dominated the local skyline by the end of the century. Moses and Ceasar Cone specifically ran the most prosperous group of plants under the name “Cone Mills Corporation.”

While Greensboro is no longer home to widespread manufacturing today, it does entertain a prosperous economy centered on industries like freight transportation and healthcare. Greensboro is also a popular tourist destination, as thousands of travelers visit every year to experience its wonderful character. Indeed, the city is replete with numerous cultural attractions, such as the Greensboro Science Center, Tanger Family Bicentennial Garden, and the Greensboro Children’s Museum. Cultural heritage travelers have enjoyed visiting Greensboro, too, who have visited destinations such as the Greensboro History Museum, the Weatherspoon Art Museum, and Elsewhere Collaborative. Even more historical locations reside just outside of Greensboro, like the renowned Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. Perhaps the most significant institution in the city is the International Civil Rights Center & Museum. The facility is located inside an erstwhile F. W. Woolworth department store, where, in 1960, four black students attending the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University organized a sit-in after they were denied service at the lunch counter on account of their race. Their protest subsequently spawned numerous other sit-ins in neighboring states, which ultimately helped bring an end to segregated dining facilities across the American South. Historians today consider the act to be a watershed moment in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

-

About the Architecture +

Thanks to the efforts of the Pass family, The Historic Magnolia House is open today for future generations to appreciate. In 1996, Sam and Kimberly Pass purchased the historic home with the intent to thoroughly renovate it into a fully functional boutique hotel. Nevertheless, their overarching vision involved restoring the architectural integrity of the structure, too. Doing so would not only preserve its institutional history, but also the stories of the greater local African American community. The project was massive in scope, with the fundraising and construction taking three decades to fully complete. The Pass family diligently worked toward renovating every single aspect of the structure’s original architecture, including restorations to the exterior trim, front door, and roof. Once around 85% of the work was finished, the Pass’ daughter, Natalie Pass-Miller, assumed control of The Historic Magnolia House. She has since served as the building’s primary steward, conducting additional renovations in recent years. Among the new construction projects done under her guidance was the refurbishment of all the guestrooms. Teaming up with designers Gina Hicks and Laura Mensch of Vivid Interiors, Miller-Pass oversaw the implementation of bold hues and Mid-Century replica furniture that helped recapture the character of the house. Furthermore, the rooms were complimented with designs that paid tribute to the many influential personalities that visited the location back during the mid-20th century.

The Historic Magnolia House also stands today as one of the finest local examples of Italianate architecture. One of the first examples of Renaissance Revival-style architecture, Italianate design principles are some of the most historic ever used in the United States. Despite its popularity in America, it was originally conceived by a British architect named John Nash at the beginning of the 1800s. Inspired by the architectural motifs of 16th-century Italy, he constructed a brilliant Mediterranean-themed estate called “Cronkhill.” Nash borrowed heavily from both Palladianism and Neoclassicism to design the building, both of which were derivatives of the Italian Renaissance art forms. Soon enough, many other architects began copying Nash’s style, using it to construct similar manors across the English countryside. The person responsible for popularizing the aesthetic the most was Sir Charles Barry, who had his own offshoot called “Barryesque.” By the middle of the century, this Italian Renaissance Revival-style architecture had spread to other places within the British Empire, as well as mainland Europe. It had even crossed the Atlantic in the 1830s, where it dominated the American architectural landscape for the next 50 years. Architect Alexander Jackson Davis promoted the style, using it to design such iconic structures as Blandwood and Winyah Park in New York. Although he was more widely known for his use of another Revival style—Neo Gothic—his work with Italianate helped cement it within the country.

But The Historic Magnolia House also showcases elements of “Queen Anne” style architecture. Considered a successor to Eastlake architecture, Queen Anne became a widely popular architectural style at the height of the Gilded Age. Named in honor of the 18th-century British monarch, Queen Anne, the architectural form started in England before migrating to the United States. Yet, its name is misleading, as it actually borrowed its design principles from buildings constructed during the Renaissance. While the appearance of Queen Anne-style buildings may differ considerably, they are all united by several common features. For instance, they are typically asymmetrical in nature, and are built with some combination of stone, brick, and wood. Those buildings even feature a large wrap-around porch, as well as a couple polygonal towers. Those towers may also be accompanied by turrets along the corners of a building’s exterior façade. Structures designed with Queen Anne-style principles may also have pitched, gabled roofs that feature irregular shapes and patterns. Intricate wood carvings are a common sight throughout their layout, too, and are often crafted in such a way to resemble different objects. As such, guests viewing the architectural features of Queen Anne architecture many feel as if they had been staring at an illusion! Clapboard paneling and half-timbering are a few other forms of woodworking that are regularly found somewhere within a Queen Anne-style structure.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Ray Charles, musician who pioneered American soul music and created countless chart-topping singles.

Lena Horne, actress and civil rights activist remembered for her roles in Stormy Weather, Cabin in the Sky, and The Wiz.

Ruth Brown, singer and songwriter known for songs like “So Long,” “Teardrops from My Eyes,” and “(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean.”

Gladys Knight, seven-time Grammy Award-winner known as the “Empress of Soul.”

Otis Redding, singer and songwriter responsible for establishing American soul music in popular culture.

Tina Turner, 12-time Grammy Award winner regarded as one of the best-selling recording artists of all time.

Ike Turner, early pioneer of rock and roll who was the bandleader of the Ike & Tina Turner Revue.

Count Basie, big band leader known for leading the Count Basie Orchestra to national prominence from Chicago.

James Brown, musician known as the “Godfather of Soul,” who is regarded as a founder of funk music.

Louis Armstrong, jazz musician regarded as one of the most influential figures in the genre.

Sam Cooke, singer and songwriter remembered today as the “King of Soul.”

Miles Davis, musician remembered as being one of the key figures in the history of jazz.

Duke Ellington's band, famous for playing at the Cotton Club.

Joe Tex, singer known for songs like, “Skinny Legs and All,” “I Gotcha,” and “Hold What You’ve Got.”

Lionel Hampton, jazz musician and bandleader known for working alongside Benny Goodman, Buddy Rich, and Quincy Jones.

Little Willie John, singer known for songs like “All Around the World,” “Need Your Love So Bad,” and “Fever.”

Logie Meachum, blues musician who was instrumental in founding the Piedmont Blues Preservation Society.

Jackie Robinson, star second basemen for the Brooklyn Dodgers who became the first African American to play Major League Baseball.

Satchel Paige, star pitcher from the Negro Leagues and Major League Baseball whose legendary career spanned five decades.

Ezzard Charles, boxing heavyweight champion remembered today as the “Cincinnati Cobra.”

James Baldwin, writer and civil rights activist known for his literary works, Notes of a Native Son, Giovanni’s Room, and Go Tell It on the Mountain.

Martin Luther King Jr., historic civil rights leader of the 1960s-era Civil Rights Movement.

Carter G. Woodson, historian and journalist who founded the prominent Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH).