Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Emily Morgan San Antonio, which is named after folk heroine from the Texas Revolution, Emily D. West.

The Emily Morgan San Antonio, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2015, dates back to 1924.

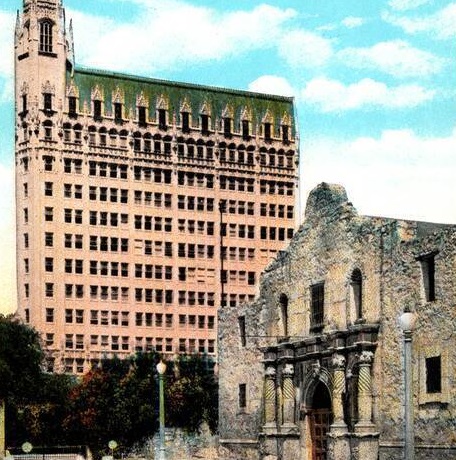

VIEW TIMELINESan Antonio had long been an incredibly prosperous metropolis by the beginning of the early 20th century. Commerce had proliferated throughout the city for years, leading to a prolonged population growth that endured for generations. Many new commercial structures were thus starting to emerge across San Antonio at the time, which significantly changed its already historic skyline. Even the city’s most historic neighborhoods underwent development, including the blocks surrounding the famed Alamo Plaza. Among the most beautiful buildings to open near the landmark was the prominent “Medical Arts Building.” Originally built in the Roaring Twenties, the location was the brainchild of real estate developer Clifton George and architect Ralph Cameron. (Interestingly, George was also an accomplished car salesman, operating a lucrative Ford dealership nearby.) Both men adored the site of the future structure—a triangular plot of land that loomed over the historic Alamo. But they did not wish to construct any ordinary office complex upon the site. George and Cameron instead yearned to create what was then known as a “medical arts” building. Medical arts buildings specifically functioned as exclusive business compounds for doctors and other medical professionals, who could practice their various specialties privately. Rival cities—like Dallas and Houston—had medical arts buildings, too, leaving George and Cameron with the impression that a strong market could exist for one in the heart of San Antonio.

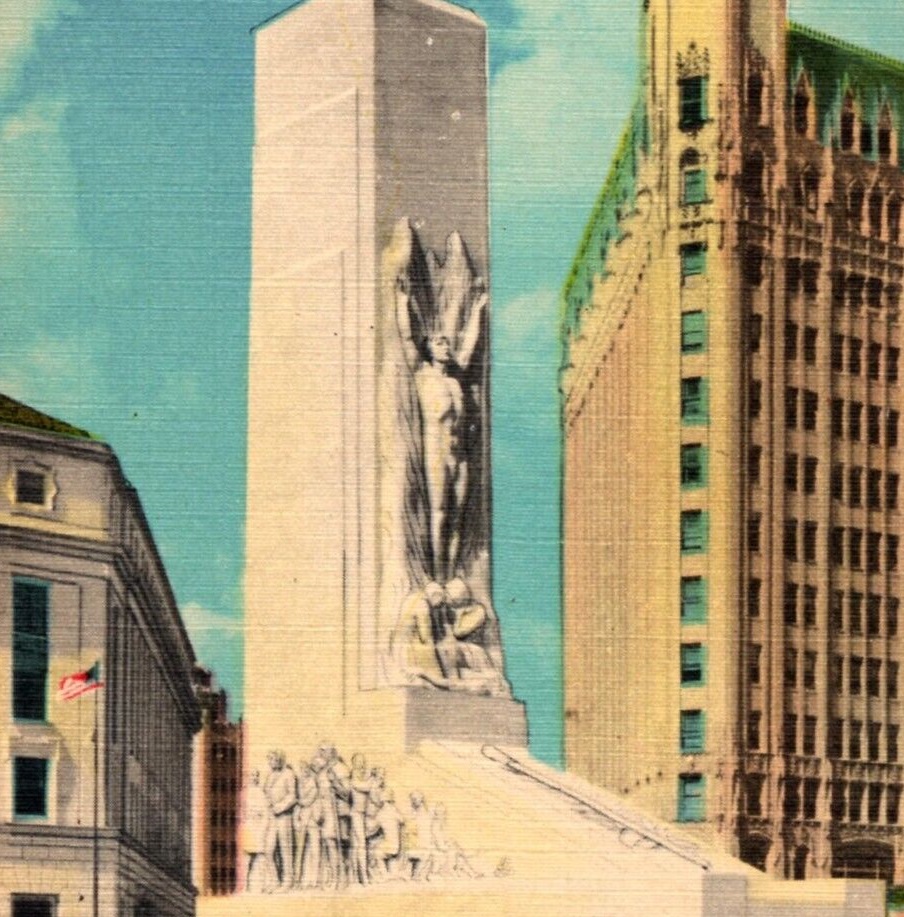

The two men began construction on their own medical arts building in 1924, with Cameron overseeing its design. Cameron did not disappoint, ultimately crafting a stunning 13-story skyscraper that displayed a gorgeous combination of Gothic Revival-style motifs. He had masterfully instituted many Gothic-inspired architectural elements throughout his design, including a steeply pitched mansard roof, terra cotta detailing, and a Châteauesque corner tower. Perhaps the most notable Gothic feature that Cameron installed were the many gargoyles that resided across its façade. In fact, Cameron even had the gargoyles humorously show a series of aliments, ranging from stomach aches to poked eyes. The new Medical Arts Building thus became a revered municipal landmark once construction finally concluded some two years later. Indeed, the structure even debuted as the tallest building in all San Antonio—a title it would hold until the opening of the Milam Building in 1927. It also earned a considerable reputation for its available medical services to the delight of its original owners. Prominent medical professionals of numerous specialties called the Medical Arts Building home, having come to adore the upscale treatment facilities that George and Cameron had built throughout the structure. In fact, the Medical Arts Building would remain at full occupancy for more than three decades, with some doctors even spending their entire careers on-site.

But by the middle of the century, most of those professionals had relocated to newer medical structures located elsewhere in San Antonio. A period of fluid ownership then transpired that saw the structure fulfill a variety of functions, including serving—ironically—as a regular office. However, the erstwhile Medical Arts Building eventually received a new lease on life when a few hoteliers acquired it in 1984. They subsequently initiated an extensive two-year-long renovation that transformed the building into a terrific business called “The Emily Morgan Hotel.” (The name was an homage to a famous young black woman who had helped the Texans win the Battle of San Jacinto in 1842—at least according to legend.) While the work had brilliantly changed the interior floorplan to offer a wealth of upscale guestrooms, it had also succeeded in restoring the building’s rich architectural character. The renovations proved to be very successful, as travelers from across the nation soon came to adore its amazing facilities and warm hospitality. Now known as “The Emily Morgan San Antonio – a Doubletree by Hilton Hotel,” this fantastic location has since remained one of the city’s best places to stay. Not only have guests continued to find its charming guestrooms to be among the finest in the city, but they have also enjoyed its proximity to prominent historical attractions like the Alamo. Cultural heritage travelers in particular have visited the hotel in great numbers, given its listing as a contributing structure within the Alamo Plaza Historic District by the U.S. Department of the Interior!

-

About the Location +

Referring to the location as “Yanaguana” (or “refreshing waters”), the Native American Payaya were the first people to inhabit the site of present-day San Antonio generations ago. They specifically lived in relative isolation as hunter-gatherers, with the San Antonio River providing a source of sustenance. But their historic seclusion came to an end once Spanish explorers began charting the region during the late 1600s. Perhaps the most significant expedition to take place was the one headed by Pedro de Aguirre, Isidro de Espinosa, and Antonio de Olivares in 1709. The latter two men were Franciscan monks, who planned on establishing several religious missions throughout the surrounding valley. Olivares in particular wrote directly to the Viceroy of New Spain—the highest-ranking Spanish official in the Americas at the time—urging him to prioritize its settlement as soon as possible. Fortunately for Olivares, his pleas eventually came to fruition when the colonial Spanish government finally commissioned the creation of an outpost along the banks of the river in 1718. Central to Olivares’ new community was a sprawling mission complex that he had erected with the help of the local Payaya. Together, the group gradually constructed the rudimentary compound out of mud, brush, and straw over several weeks. Olivares then christened the entire facility as the “Misión San Antonio de Valero” in honor of Saint Anthony of Padua.

Olivares had also received additional assistance from Martín de Alarcón, governor for the province of Spanish Texas. Interested in using the nascent mission as a buttress against potential foreign military incursions from French Louisiana, Alarcón proceeded to construct a fort named the “Presidio de Béxar” on the opposite side of the riverbank. He further linked the two facilities by way of a bridge and even established an agricultural canal that was capable of supporting both locations. At first, only a few friars and their Native American converts inhabited the compound, as well as a small garrison of colonial soldiers. Nevertheless, the Spanish Crown ultimately directed a few dozen families from the Canary Islands to settle the site, too. Arriving in 1731, those pioneers set about founding their own village nearby, which they called “San Fernando de Béxar.” All three destinations would gradually emerge as the most important settlements in Spanish Texas, given their proximity to the San Antonio River and the Camino Real trail that led deeper into the Texan wilderness. In fact, San Fernando de Béxar actually became the official capital for the whole province in 1773! The town had expanded exponentially as a result, reaching the size of a city by the dawn of the 19th century. Driving this population growth was the arrival of the first Euro-American settlers, thanks in part to the politicking of Stephen Austin. (European immigrants would later supplement the city’s population, including thousands of Germans.)

Now largely referred to as “San Antonio,” the community was then gripped with patriotic fervor amid the greater backdrop of the Mexican Wars of Independence. Some of its leading citizens even participated in the drafting of the first Federal Constitution for the newly created state of Mexico in 1824. But this desire for self-government grew more intense in San Antonio once military general Antonio López de Santa Anna abolished the constitution not long thereafter. The city’s residents thus eagerly supported the Texas Revolution when it erupted in the 1830s. San Antonio itself even became a battlefield, with its militia driving out the local Mexican garrison during the Siege of Béxar. Even though the rebels managed to hold onto the city for some time, general Santa Anna eventually arranged a counterattack in 1836. The remaining Texan forces in turn retreated into the Misión San Antonio de Valero, which had become known as the “Alamo.” (Some scholars speculate that the name was an homage to a local cottonwood grove, since the Spanish word “álamo” meant “cottonwood.”) Legendary figures like James Bowie and Davy Crockett fought the Mexican Army in the subsequent Battle of the Alamo, dying to a single man after holding out against overwhelming odds for 13 days. Seen as martyrs by the rest of the movement, their sacrifice galvanized the other revolutionaries to defeat General Santa Anna at the climactic Battle of San Jacinto a month later.

San Antonio would continue to be one of the region’s most important metropolises in the wake of the revolution, especially once Texas joined the United States in the 1840s. Indeed, substantial economic activity transpired all throughout San Antonio as soon as the first railroads enabled widespread industrialization to occur during the Gilded Age. But San Antonio had also become a bastion for the famous Texas ranching trade, due to its role as the main embarkation point for the Chisolm Trail. The city has since maintained its revered reputation well into the present, anchoring the southwestern corner of a prolific megaregion called the “Texas Triangle.” However, its distinctive cultural identity has attracted countless tourists every year, all of whom are eager to experience its unique heritage. Many fascinating attractions are located within San Antonio as such, including the Tower of the Americas, HemisFair Park, the San Antonio Museum of Art, and the San Antonio River Walk. Of course, the Alamo remains the city’s most celebrated historic destination, bearing the distinction of being both a U.S. National Historic Landmark and a UNESCO World Heritage Site! (Four other missions located outside of San Antonio are also a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the “San Antonio Missions National Historical Park.”) Few other places in the United States can truly offer such a wonderful experience than San Antonio.

-

About the Architecture +

The Emily Morgan San Antonio – a DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel stands today as a brilliant example of Gothic Revival architecture in the United States. Gothic Revival-style architecture itself was part of the artistic movement known as “Romanticism” that had swept through Europe and North America throughout much of the 19th century. This demarcated a distinctive break from the Neoclassicism of the century prior, which drew its architectural inspiration from the Greco-Roman civilizations of antiquity. The desire for the medieval design principles of Gothic Revival architecture reflected a broader trend within Western societies—particularly in European countries—to preserve the past in some meaningful way. Architects thus took to preserving the surviving buildings from the period, while also creating new ones that mirrored the aesthetic. The most common structural elements incorporated into buildings developed with Gothic Revival style were the pointed arch. This profound feature manifested in windows, doors, and rooftop gables. But it also influenced the development of entire substructures, causing the creation of such features as mock parapets, conical towers, and high spires. Other characteristics associated with Gothic Revival-style architecture included a special kind of wooden trimming known as either “vergeboards” or “bargeboards.” Porches also featured turned posts or slender columns, while the roof was often deeply pitched and lined with dormers. Architects typically used this style for rural buildings set within a historic village or town, although some in the field—such as Ralph Cameron—chose it for commercial structures from time to time. Churches were the buildings that featured Gothic Revival style the most, as their natural layout was well-suited to showcase the best of the form. Nevertheless, other buildings made use of the aesthetic, too, including hotels, banks, and government offices.