Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

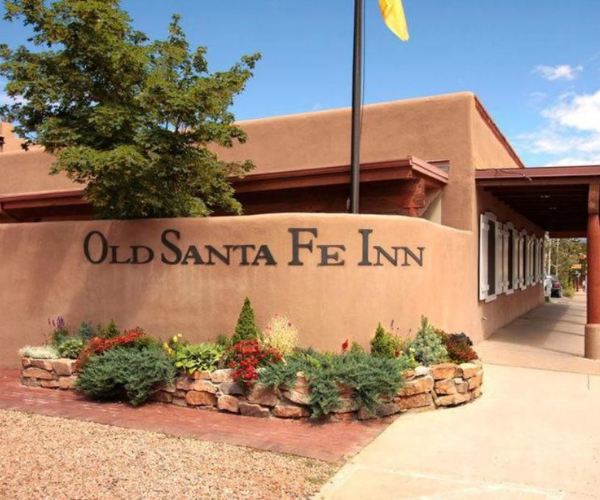

Discover Piñon Court by La Fonda, which originally debuted decades ago as the quaint, pueblo inspired Galisteo Inn.

Piñon Court by La Fonda, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2022, dates back to the 1930s.

VIEW TIMELINELocated in the heart of historic Santa Fe, New Mexico, the Piñon Court by La Fonda has offered high-end hospitality for years. Its history is quite fascinating, too, beginning at the start of the 1930s. By this point in Santa Fe’s history, the city had started to evolve into a popular holiday destination. Its climate had generated a ton of interest among ordinary Americans, who had begun traveling across the country en masse via passenger trains and personal automobiles. Many had specifically come to experience the area’s warm, dry weather, which could help combat debilitating respiratory illnesses like tuberculosis. A smaller number of visitors had also learned of the city’s unique appearance, prompting them to spend weeks at a time exploring its landscape. Among their number were artists like Georgia O’Keeffe, who created brilliant paintings of Santa Fe and its surrounding geography. It was within this environment that a robust local tourism industry emerged that created dozens of exciting hotels and resorts. The Galisteo Inn was one of those facilities, hosting all kinds of motorists that had made the long trek along historic Route 66. The inn continued to entertain guests from around the nation for many decades thereafter, until it was transformed into an office space around the middle of the century. But a family of real estate developers known as the Barkers acquired the site in 1991. Caring for the building immensely, they decided to rehabilitate the erstwhile inn’s historical character. Construction thus began several years later to turn the structure back into a charming boutique hotel. When the work finally concluded in 2003, the rebranded “Piñon Court by La Fonda” immediately established a great reputation for comfort and luxury. More recently in 2022, the Piñon Court by La Fonda was acquired by the same ownership group that operates another member of Historic Hotels of America, La Fonda (1922). Now a part of the “La Fonda Family,” the Piñon Court by La Fonda is guaranteed to appeal to countless travelers yet again for generations to come.

-

About the Location +

Santa Fe, New Mexico, is one of the most historic capital cities in America, having been founded around the same time as Jamestown, Virginia. While a tiny frontier outpost resided in the region as early as 1607, Santa Fe was not formally settled for another three years. The Spanish conquistador, Don Pedro de Peralta, had traveled north to the community and decided to transform it into an actual town. Peralta was the acting governor of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, which functioned as the colonial administrative region for the Spanish lands that were located between the provinces of Texas and California. He subsequently called the new settlement, “La Villa Real de la Santa Fé de San Francisco de Asis,” and declared it the capital of Nuevo México. Several new administrative buildings then emerged around a quaint central plaza, such as the Palacio de los Gobernadores (Palace of the Governors). The locale continued to represent the authority of the Spanish Crown in Nuevo México for the next several decades, until an uprising by the local Pueblo people drove out the settlers in 1681. Poor treatment and scant political representation in the colonial administration had fomented the revolt, which successfully forced all the Spanish and Mexican settlers to flee as far south as El Paso. Don Diego de Vargas eventually recaptured all of Nuevo México nearly ten years later, leading to the repopulation of La Villa Real de la Santa Fé de San Francisco de Asis. Subsequent generations of colonial governors—as well as the population as a whole—adopted a policy that sought better cultural relations between the two societies, ushering in a period of relative peace that lasted for more than a century.

La Villa Real de la Santa Fé continued to operate as the main administrative capital for Nuevo México right up until the Mexican War for Independence erupted in 1810. After more than 11 years of hard fighting, Mexico seceded from the Spanish Empire to form its own nation. Santa Fe remained the capital of the region, even as it became a province of the newly independent Mexico. The town had grown into something of a city by this point, with several thousand settlers living within its boundaries. Its emerging commercial opportunities soon attracted traders from the United States, who started traveling to the area in large numbers. Their migration south became all the easier when William Becknell constructed the 1,000-mile-long pathway known as the “Santa Fe Trail.” Americans quickly established makeshift shops all along the historic central plaza, making it a major economic center in Mexico’s frontier. The United States eventually seized the city—along with the rest of Nuevo México—following its victory in the Mexican-American War. Nuevo México was reborn as the “Territory of New Mexico” with Santa Fe serving as its capital. The new American administration had also taken to referring to the city simply as “Santa Fe,” although its original name remained unchanged. The town only kept growing and its size expanded exponentially. Some of the city’s most recognizable landmarks appeared during this time, such as the great Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. Then, in the 1880s, Santa Fe was connected to the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, which caused an economic renaissance to transpire throughout the entire city. But corruption also spread across Santa Fe, with even some of the era’s greatest outlaws—like Billy the Kid—frequenting the area regularly.

Fortunately—thanks in large part to the efforts of Governor Lew Wallace—federal administrators were able to clean up the town. (Wallace was a Union war hero and author of Ben-Hur). Despite its brief time spent as a hive for criminal activity, people still continued to relocate to Santa Fe. Its importance to New Mexico’s political landscape remained intact, too, serving as its capital when it finally became a state in 1912. But some of the new arrivals were attracted to the city not only for its economic prospects, but its dry, warm climate. People suffering from tuberculosis particularly found the area’s environment intriguing, as it helped them combat the effects of their debilitating illness. Not long thereafter, regular Americans began heading south to the city upon hearing stories of its beautiful weather. As such, a vibrant tourism industry appeared to serve the influx of new travelers. Artists even began relocating to Santa Fe, inspired by the region’s desert landscape. Among the artists who spent time in the city in the mid-20th century was the iconic Georgia O’Keeffe, who created many wonderful paintings of New Mexico’s geography. Those intellectuals developed a thriving community of art galleries and studios that has lasted well into the present. In fact, UNESCO has even recently included Santa Fe within its Creative Cities Network. Today, much of Santa Fe’s historic downtown is recognized collectively as a U.S. National Historic Landmark. Some of the specific buildings themselves are identified as individually National Historic Landmarks, too, including the prolific Palace of the Governors.

-

About the Architecture +

Piñon Court by La Fonda displays a wonderful architectural aesthetic called “Spanish Revival.” Also known as “Spanish Eclectic,” Spanish Colonial Revival Revival-style architecture itself is one of the most popular throughout the entire United States. It has influenced architects for generations, especially those located in the western half of the country. True to its name, Spanish Colonial Revival-style is a representation of themes typically seen in early Spanish colonial settlements. Original Spanish colonial architecture borrowed its design principles from Moorish, Renaissance, and Byzantine forms, which made it incredibly decorative and ornate. The general layout of those structures called for a central courtyard, as well as thick stucco walls that could endure Latin America’s diverse climate. Among the most recognizable features within those colonial buildings involved heavy carved doors, spiraled columns, and gabled red-tile roofs. Architect Bertram Goodhue was the first to widely popularize Spanish Colonial architecture in the United States, spawning a movement to incorporate the style more broadly in American culture at the beginning of the 20th century. Goodhue received a platform for his designs at the Panama-California Exposition of 1915, in which Spanish Colonial architecture was exposed to a national audience for the first time. His push to preserve the form led to a revivalist movement that saw widespread use of Spanish Colonial architecture throughout the country, specifically in California and Florida. Spanish Colonial Revival-style architecture reached its zenith during the early 1930s, although a few American businesspeople continued to embrace the form well into the late 20th century.