Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

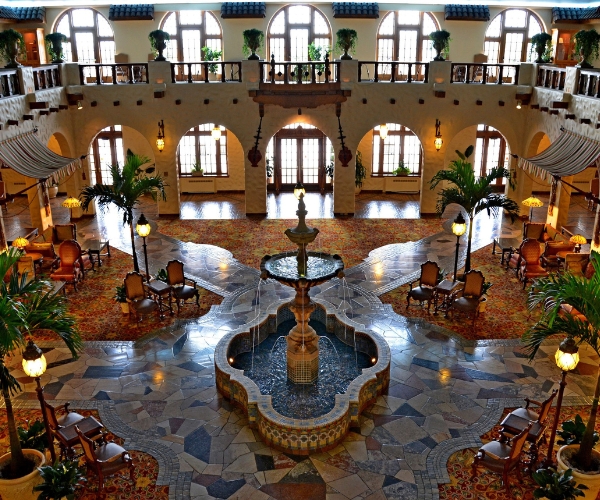

Discover the Nassau Inn, which has entertained numerous guests visiting Princeton University for generations.

Located down the road from the revered Princeton University, the Nassau Inn has long been celebrated for its extraordinary hospitality. But while the current iteration of the historic Nassau Inn debuted a century ago, its institutional history is far more extensive. Its origins trace back to the mid-18th century when prominent colonial judge Thomas Leonard created the first version of the structure to function as his private residence. One of the individuals responsible for establishing the current Princeton University campus, Leonard had constructed a quaint country manor upon a verdant lot within walking distance of the school. However, Leonard only lived inside the house for a couple of years before passing away during the late 1750s. In the wake of his death, aspiring hotelier Christopher Beekman acquired the dwelling and reopened it as a tavern called the “College Inn.” Beekman thrived as the proprietor, whose management style gave the business a reputation for always offering an enjoyable, comforting atmosphere. The College Inn emerged as the center for all social life in Princeton by the eve of the American Revolution, coming to host various community gatherings almost every night. The most notable events held in the building were the meetings of the local Committee of Safety, an informal civic organization that sought to garner patriotic sentiment in defiance to British authorities.

The College Inn became a place of great patriotic fervor in consequence, with the committee members reading the political treatises of noted activists like Robert Morris and Thomas Paine whenever on-site. (Oral tradition states that Morris, Paine, and other revolutionaries—such as Paul Revere—were invited to join some of the Committee’s sessions, too!) Possessing a strong association to the American independence movement, the College Inn was a popular destination among delegates traveling south to attend the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. The structure eventually found itself on the frontlines of the American Revolutionary War, as Princeton changed hands numerous times throughout the course of the conflict. The College Inn accommodated soldiers from both sides, depending on who occupied the town at the time. For instance, British and Hessian officers were regular customers after their capture of Princeton in 1777, only to be replaced by American soldiers following the Battle of Princeton several months later. The College Inn managed to survive the ordeal, resuming its status as one of the best spots to visit in the region once the war had ended. In fact, the College Inn had even entertained several notable dignitaries when the Continental Congress briefly relocated to Princeton University’s Nassau Hall in 1783.

The popularity of the business endured for many decades thereafter and eventually rebranded as the “Nassau Inn” in honor of Princeton University. But unfortunately for the historic building, it began to show its age toward the beginning of the early 20th century. To remedy the situation, a prominent Princeton University donor, Edgar Palmer, decided to revitalize the inn amid his efforts to redevelop downtown Princeton during the 1930s. Palmer specifically convinced city officials to move the business into the heart of his larger mixed-use commercial development that he named “Palmer Square.” His primary selling point was the fact that Nassau Inn would act as the centerpiece of Palmer Square, its brilliant, colonially inspired architecture inspiring contemporary visitors to experience the whole compound. Construction subsequently began in 1937 and took Palmer’s team a year to complete. Palmer spared no expense, investing heavily to see that the building’s fascinating character was revived within the new structure. When the work on the resurrected Nassau Inn concluded, it quickly reemerged as one of the most respected holiday destinations in New Jersey. The Nassau Inn has maintained its prestigious identity in the present, serving as a top venue for guests visiting Princeton University. It also remains the main attraction of Princeton’s equally historic Palmer Square, which continues to thrive as a popular site for shopping and fine dining today.

-

About the Location +

Although the Lenape Native Americans had long lived in the area for generations, Princeton emerged during the widespread European settlement of present-day New Jersey during the late 17th century. The earliest houses to appear within the community debuted gradually throughout the 1680s and 1690s, beginning with Henry Greenland’s extensive estate in 1683. (Greenland opened a tavern nearby, occupying the spot that would later host the historically significant Kingston Mills.) Among the most prominent families to establish residences were the Clarks, Oldens, and Stocktons, who helped found some of the earliest businesses in the area. Meanwhile, a few Quakers managed to create a small village near a local body of water referred to as the “Stony Brook.” Together, those various social groups gradually coalesced into a single community centered along a wilderness trail that would eventually become Princeton’s main road, Nassau Street. An actual town had emerged by the beginning of the 18th century, which primarily served the numerous farms out in the surrounding countryside. Interestingly, the inhabitants used a variety of names to refer to their new community, calling it “Princetown” and “Prince’s Town” before collectively settling upon “Princeton.” (While surviving historical records have not revealed the true inspiration for the moniker, most have inferred that the likeliest source was King William III of England. Princeton remained small for many decades after, with its population numbering in the hundreds.

The town managed to attain tremendous cultural significance following the relocation of the College of New Jersey from Newark in 1756. The move had been a great undertaking for the town’s leading residents, who championed its equitable distance to both Philadelphia and New York City as a boon for prospective students. To house the school, those same civic leaders managed to construct a gorgeous multistory edifice called “Nassau Hall” toward the center of town. Designed by the renowned architect Robert Smith, Nassau Hall’s classically inspired architecture and iconic cupola soon came to brilliantly dominate Princton’s skyline. Now home to a prestigious educational institution, Princeton developed a reputation as one of New Jersey’s most prolific settlements. The college quickly contributed to the fomentation of the American Revolution, with its administrators crafting a curriculum meant to train a new generation of leaders for the nascent United States. Its president at the time, John Witherspoon, acted as one of the signers for the Declaration of Independence. (He was joined by another Princeton-native, Richard Stockton, who had also played a pivotal role in founding the college’s campus downtown.) Both the College of New Jersey and Princeton would go on to experience the American Revolution more directly over the next few years, bearing witness to one of the most crucial American victories in the entire conflict.

George Washington and the Continental Army specifically routed a British column right outside of the town during the eponymously named Battle of Princeton in 1777, forcing the Royal Army to completely withdraw from New Jersey for the duration of the war. One of the most memorable events to occur in the area in relation to the Revolution was the brief time Nassau Hall operated as the official capital of the nation in 1783. George Washington stepped inside the hallowed structure to officially receive the country's thanks for his service. Princeton retained its earlier cultural importance in the wake of America’s birth, becoming celebrated for its rich affiliation with science and the arts. Much of this repute stemmed from the continued presence of the college, which had rebranded as the more recognizable “Princeton University” in 1896. Princeton and Princeton University have retained their prestigious statuses in the present, with the latter proudly bearing the distinction as being one of the country’s internationally renowned eight Ivy League schools. For their rich contributions to American history, each site currently bears multiple listings in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. Princeton University’s iconic Nassau Hall bears a rare designation as a U.S. National Historic Landmark, too, as does several historic homes in Princeton proper, like Morvern, Prospect, Wetland Mansion, and the Albert Einstein House. (For reference, Einstein had started working at the Princeton University affiliated Institute for Advanced Study in 1933.)

-

About the Architecture +

The Nassau Inn today highlights some of the finest Colonial Revival architecture in New Jersey. Colonial Revival architecture itself is the most widely used building form in the entire United States today. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined Colonial Revival-style façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, as well. This building form remained immensely popular for years until it declined in popularity in the late 20th century. Nevertheless, architects today still rely upon Colonial Revival architecture, using the form to construct all kinds of residential buildings and commercial complexes. Many buildings constructed with Colonial Revival-style architecture are identified as historical landmarks at the state level, while the U.S. Department of the Interior has even listed a few in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.