Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

the ledges hotel history

Discover the Ledges Hotel, utilizing its industrial framework amidst striking rock ledges and waterfalls, resulting in a memorable and luxurious establishment.

The Ruins at Ledges Hotel

Discover the history and heritage of Ledges Hotel, located on the ruins of the 19th century O'Connor glass factory.

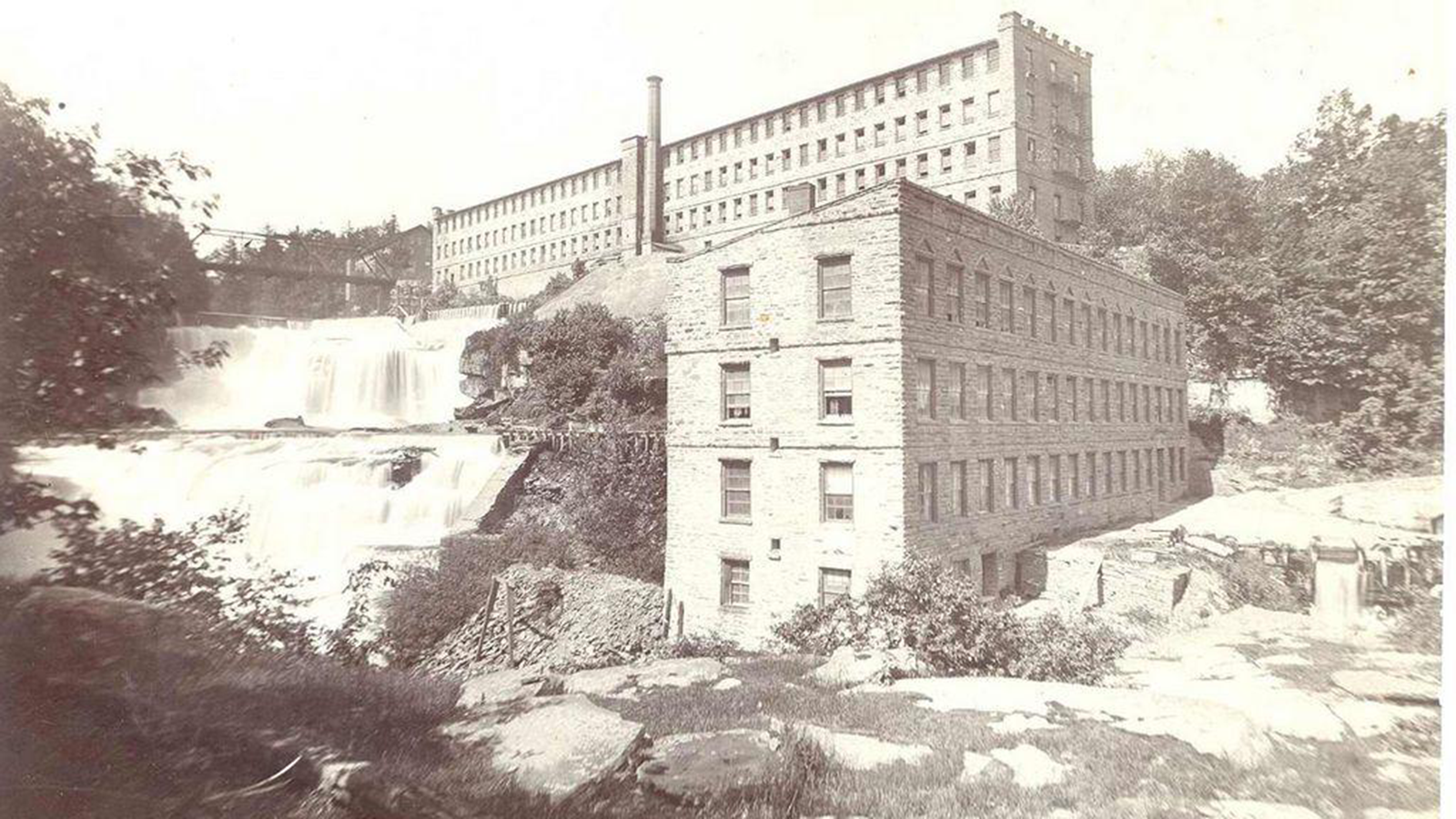

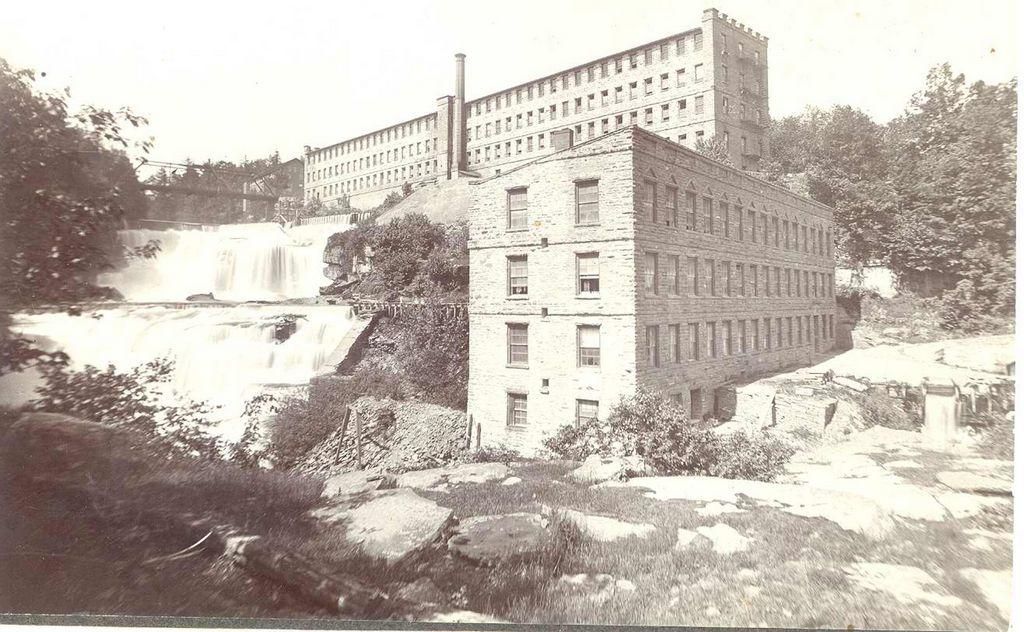

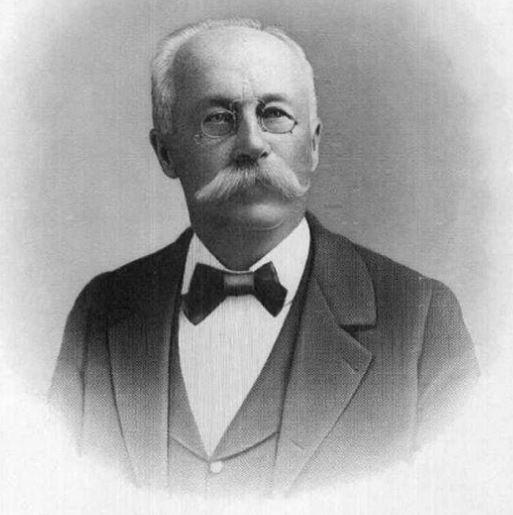

WATCH NOWBuilt in 1890 by John S. O'Connor, the Federal-style bluestone building that currently houses the Ledges Hotel was erected as a factory for glass manufacturing. This fantastic three-story plant was developed at the foot of the tranquil Wallenpaupack Falls with pediment windows, shed-style roof, and decorative cornices. Known as the “J.S. O'Connor American Rich Cut Glass Factory,” the building specialized in producing cut glass using Dorflinger blanks. The structure was quite the engineering marvel at the time, for it relied upon electricity generated via the creek located direct behind the building. Inside, the factory held the capacity to house some 200 cutting frames, while a series of powerful turbines resided in the basement below. O’Connor also placed all of the administrative offices, roughing, and stockrooms next to the cutting frames as a way to better supervise productivity on-site. Meanwhile, the designing, smoothing, and polishing departments resided on the second and third stories. O’Connor himself was considered to be one of the foremost glass cutters in the whole country. Born in Ireland and moved to America as a child, John S. O'Connor got his start as a glass cutting apprentice in the factories of New York City. His skills were instantly recognized by Christian Dorflinger of White Mills, where he worked after serving in the American Civil War. O'Connor became a pioneer of the glass industry shortly thereafter, going on to help create many other plants. Among the prestigious companies that he assisted in opening included the Keystone Cut Class Company and Wagnum Cut Class Company.

O’Connor nonetheless made his greatest impact on the industry when he began producing his own iconic glass patterns between 1880 and 1906—an era that is now remembered as America’s "Brilliant Period" of glass cutting. Among his most noteworthy designs included Parisian, Florentine, and Princess, which he produced from his John S. O'Connor American Rich Cut Glass Factory. In fact, many contemporaries of O’Connor’s observed that his plant was one of the most important glass cutting factories in the United States. Even after T. B. Clark purchased the factory from O'Conner for his own Maple City Cut Class Company in 1902, catalogs offering O'Conner's brilliant cut pieces were still widely issued across the nation. Nevertheless, the factory shifted from glass cutting to silk production when H.W. Kimble moved his H. W. Kimble Silk Company into the building after World War I. But several decades later in 1943, the factory was sold to the Arrow Throwing Mill, which made a variety of textiles. It even provided yarn for emblems and nylon for parachutes during World War II. Then in the late 1980s, the factory was converted into an inn called the “Country Inn.” Known as the “Ledges Hotel” today, this spectacular historic hotel in pennsylvania combines its original elements with modern upgrades to create a luxurious and historically rich establishment. Partnering with world-class architects of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson and custom furniture designers from Boyce Products, Ledges Hotel embodies both luxury rustic charm and its rich historic character. Now listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, Ledges Hotel has been a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2013.

-

About the Location +

The borough of Hawley is a bucolic community nestled in the heart of Pennsylvania’s Poconos region. While Hawley itself was first incorporated in 1884, people had actually been settling the area a century prior. In fact, the first pioneers arrived in the 1790s, allured by tales of the region’s ability to help cultivate industry. Indeed, the land surrounding modern-day Hawley was replete with many water sources that could help power rudimentary mechanical equipment. The mighty Wallenpaupack Falls was the greatest local natural resource manufacturers sought to utilize, as its cascading waters were powerful enough to fuel numerous mills and factories in the area. Among the initial industrial operations to appear were glassworks, which began to populate the countryside in the early 1800s. Several nearby communities—including Bethany, Rockville, and Traceyville—hosted some of the first, with the Bethany Glassworks producing an annual output of some several thousand dollars each year. The factories subsequently spread all over Wayne County throughout the remainder of the century, arriving in places like Hawley around the apex of the Gilded Age. Most factories created goods like windowpanes and jars, although a few others—such as John S. O’Connor’s plant—made popular ornamental glassware. Glass manufacturing remained the primary industrial activity around Hawley for some time before gradually disappearing after World War I. In its place, a few industrialists began to convert the factories for silk throwing and a few other economic activities. Today, Hawley (and its neighboring towns) now entertain a vibrant tourism industry, which draws upon the inherent beauty of the Poconos.

The Poconos themselves are a massive mountain chain that shadows the Delaware River before ending near the Lehigh Valley. Its northern reaches drift into New York, where they link up with the Catskills. Some of the summits in the Poconos are capable of reaching several hundred feet in elevation, with the highest peak measuring some 1,800 feet. People have long inhabited the region, as many Native American societies—including the Lenape, Iroquois, and Shawnee—once called the Poconos home. In 1742, English and German settlers began arriving en masse, although the Dutch had created a few outposts on the fringes of the mountain chain a century prior. Small sustenance farms populated the areas where the land was flat and the soil arable. But the Poconos were soon celebrated regionally for its serene environment. The area, thus, gradually built a reputation as a secluded retreat, with the first hotel opening in 1829. Yet, its true metamorphosis into a major holiday destination did not truly come to fruition until the mid-20th century. World War II heavily spurred this development, as American soldiers returning from overseas took their loved ones up into the mountains for a much-needed vacation. Its popularity exploded tenfold once the war ended, with families traveling from all over the nation to enjoy its natural beauty. Since the 1990s, the Poconos have been among the most cherished vacation getaways in all of America, with tens of thousands visiting every year.

-

About the Architecture +

When John S. O’Connor first developed the J.S. O'Connor American Rich Cut Glass Factory, he created a beautiful three-story bluestone building at the base of the Wallenpaupack Falls. The exterior of the building specifically featured walls that were nearly three feet thick and covered by nearly 100 windows. O’Connor also installed a slanted shed rooftop, which he developed completely out of slate. Inside, the factory held the capacity to house some 200 cutting frames, while a series of powerful turbines resided in the basement below. O’Connor also placed all of the administrative offices, roughing, and stockrooms next to the cutting frames as a means to better supervise productivity. Meanwhile, the designing, smoothing, and polishing departments resided on the second and third stories. O’Connor supplied power to the whole plant through a power system connected to the falls, which helped generate a constant source of electricity. Renovations to the structure remained scant for some time thereafter, even as new owners began to use the factory for different manufacturing operations. Only the basement saw any real work, becoming storage space around the time the building played host to a few silk throwing companies. But the factory’s entire interior floorplan was changed dramatically when it underwent renovations to open as an inn in 1988. The hoteliers subsequently transformed the first floor into a parlor and laundry, as the second and third stories held a variety of upscale suites and guestrooms. They also installed the inn’s current deck and internal lobby space, too. Amazingly, the renovations managed to perfectly preserve the building’s historic façade, giving guests today an authentic cultural heritage experience found in few other hotels across the United States.

The Ledges Hotel also displays one prominent architectural style: Federal—or at least a 20th-century recreation of it. Historically speaking, Federal architecture dominated American cities and towns during the nation’s formative years, which historians best identify as lasting from 1780 to 1840. The name itself is a tribute to that period, in which America’s first political leaders sought to establish the foundations of the current federal government. Fundamentally, the architectural form had evolved from the earlier Georgian design principles that had greatly influenced both British and American culture throughout most of the 18th century. The similarities between the two art forms have even inspired some scholars to refer to Federalist architecture as a mere refinement of the earlier Georgian aesthetic. Oddly enough, though, the architect deemed responsible for popularizing Federal style in the United States, was in fact, not an American. Robert Adams was the United Kingdom’s most popular architect at the time, with his work largely involved providing his own spin on the infusion of neoclassical design principles with Georgian architecture. (This is also the reason why some refer to Federal architecture as “Adam-style architecture.”) As such, his new variation spread quickly across England, defining its civic landscape for much of the Napoleonic Era. Despite the bitter resentments that most Americans harbored toward Great Britain at the time, their cultural perceptions of the world were still largely influenced by the mother country. Thus, Adams’ new take on Georgian architecture rapidly spread throughout the United States as it had previously across the Atlantic.

Unlike many other popular American architectural forms, Federal style is easily recognizable due to its unique symmetrical and geometric design elements. Most structures created with Federal architecture typically stand two to three stories in height and are rectangular (sometimes square) in their overall shape. While the buildings normally extended two rooms in width, larger structures would usually contain several more. In some cases, circular or oval-shaped rooms functioned as the center living space. The outside façade of a Federal-style building was simplistic in their appearance, although some detailed brass and iron decorations made their appearance, too. Perhaps the most common form that the ornamentations assumed were elliptical figures, as well as circular and fan-shaped motifs. Architects concentrated those features around the front entrance, where cornices, iron molding, and a beautifully sculpted fanlight resided. (Fanlights are a regular design element for Federalist buildings, appearing in other locations throughout the top of the structure, as well). The exterior walls themselves were primarily composed of clapboard out in the country but consisted of brick in urban areas. Palladian-themed windows also proliferated throughout the façade, installed in a way that conveyed a deep sense of balance. Roofing was also hipped and contained simple gables and dormers that allowed for natural light to more easily infiltrate the upper echelons of the structure.

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Featured on Travel Channel entitled, "Poconos Factory Turned Hotel." Interested parties may view that video snippet here.