Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

hotel bethlehem history

Discover Historic Hotel Bethlehem, which was built by Charles M. Schwab, steel magnate of American Steel and the Bethlehem Steel Company.

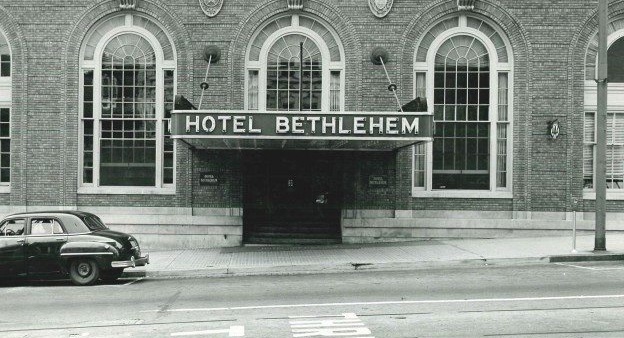

Historic Hotel Bethlehem, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2002, dates back to 1922.

VIEW TIMELINEWelcome to the Historic Hotel Bethlehem

Built in 1922, the Historic Hotel Bethlehem is one of Pennsylvania’s finest holiday destinations. Watch this video to learn more about its institutional history and stunning amenities.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2002, Historic Hotel Bethlehem is one of the nation’s most prestigious holiday destinations. Built at the onset of the Prohibition era, this stunning historic hotel has entertained countless guests for years. Yet, this little spot in the center of town has a history with deep roots. In 1741, a group of Moravian missionaries constructed the famous First House of Bethlehem on the grounds. It was a rustic log cabin that sheltered the Moravians while they developed the rest of Bethlehem over the next few years. (The Moravians themselves had come as missionaries to proselytize the local Lenape and non-denominational German farmers that inhabited the region.) They remained incredibly passionate about their mission, and within 20 years, they had constructed more than 50 unique buildings in the center of Bethlehem. A few of those new structures even housed several unique industries, including potteries, tanneries, smiting complexes, and dye houses. The site of today’s Historic Hotel Bethlehem changed as well, for the Moravians replaced the First House of Bethlehem with a general store in 1794. In fact, this business would gradually morph into a gorgeous inn over the next three decades, becoming the “Golden Eagle Hotel” at the beginning of the 1820s. That incarnation of the Historic Hotel Bethlehem continued to operate unhindered right up until 1919, when the building began temporarily housing convalescing soldiers upon their return from the European battlefields of World War I. Many illustrious guests had also traveled to the Golden Eagle Hotel, including Mark Twain, William Waldorf Astor, and U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, adding to the rich hotel Bethlehem history.

Then, two years later, the great steel magnate Charles M. Schwab purchased the location and decided to build an entirely new hotel that would be the crown jewel of Bethlehem. The President of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, Schwab specifically envisioned a grand Beaux-Arts-style edifice that featured state-of-the-art innovations like his company’s fireproof steel I-beams. He subsequently formed the Bethlehem Hotel Corporation and raised $1 million of stock to finance the building’s development. Construction began in earnest in 1921, with crews working tirelessly to create Schwab’s masterpiece. Many brilliant amenities appeared inside the hotel, including a barbershop, a shoeshine, and a “club room,” which today would serve as the equivalent to a modern fitness center. It even featured a spectacular cigar shop that sold all kinds of luxurious products, such as Dimisco Coronas cigars. (Interestingly, the Historic Hotel Bethlehem possesses on such “Boite Nature” cigar box that had the hotel’s logo placed all over the cover, suggesting that the business had its own specially packaged cigars.) When the structure finally debuted as the “Hotel Bethlehem” in 1922, it stood as one of the most beautiful buildings in all of Bethlehem. People from across the country soon began reserving guestroom in large numbers, including some of America’s most distinguished citizens. Amelia Earhart flew her plane from Rochester to Bethlehem, in order to attend a banquet held in her honor inside the hotel. Winston Churchill—a close friend of Charles M. Schwab—stayed at the hotel while paying a visit to the Bethlehem Steel Corporation. And both Henry Ford and Thomas Edison visited the business to discuss the latest technological inventions of the age.

The hotel never lost its appeal among the nation’s superstars, as great icons like Shirley Temple, Muhammad Ali, and Jack Nicklaus graced it with their presence at one point or another. But U.S. presidents were the greatest patrons to arrive at the Historic Hotel Bethlehem. For instance, President Dwight D. Eisenhower stayed while he worked hard to mediate an end to the Bethlehem Steel Strike in the late 1950s. (Eisenhower was specifically worried that a lack of steel would prove detrimental to the nation’s military and defense apparatus.) John F. Kennedy reserved a night in the Bethlehem Steel Suite when he stopped in Bethlehem during his bid for the White House in 1960. Throngs of adoring supporters attempted to rush into the building after they learned of his arrival. Kennedy went on to attend a fundraising breakfast in the hotel the next day, before leaving for a campaign rally in Allentown. (The Historic Hotel Bethlehem has also hosted the likes of Gerald Ford and Bill Clinton.) Today, the Historic Hotel Bethlehem continues to be among the most celebrated vacation retreats in the Pennsylvania. It proudly displays its story in its “Hall of History” down in the lower lobby. Artifacts from the hotel are on display, as well as various objects related to Bethlehem’s history. Perhaps the most cherished item in its collection is a painting created specifically for the hotel by military artist George Gray. Dating to 1937, the painting depicts the transformation of the culture surrounding the building. The Historic Hotel Bethlehem is also recognized today by the U.S. Department of the Interior as a contributing structure to the “Central Bethlehem Historic District.”

-

About the Location +

Bethlehem itself dates back to the mid-18th century, when a small band of 14 Moravians founded a mission community at the confluence of the Monocacy Creek and Lehigh River. At the time, the area was largely inhabited by the Lenape Indians, as well as non-denominational German sustenance farmers. As such, the Moravians hoped to spread the word of their faith to the people who dwelt in that region of Pennsylvania Colony. Led by missionaries David Nitschmann and Count Nicolaus Zinzendorf, the Moravians subsequently purchased a 500-acre tract of land from William Allen. (Allen was a wealthy politician who would eventually create the nearby community of Northampton Towne—known as Allentown today—several years later.) On Christmas Eve, the Moravians gathered to celebrate the holiday season, as well as the founding of their town. While signing a hymn with the stanza, “Not Jerusalem, Lowly Bethlehem,” Count Zinzendorf petitioned his fellow missionaries to call the settlement “Bethlehem.” The count allegedly told the congregation: “Brothers, how more fittingly could we call our new home than to name it in honor of the spot where the event we now commemorate took place. We will call this place Bethlehem.”

The Moravians set about developing their town the following spring, erecting the first structures out of hewn logs from local white oak trees. Many people from the East Coast gradually moved to Bethlehem and raised their own buildings within the community. In just a handful of years, the town was home to 35 different industries that included butcheries, tanneries, smiting complexes, dye houses. There were also a few specialized shops that manufactured clocks, candles, and fine linens. As new wealth flowed into the town, so too did better building materials. Soon enough, the log cabins were replaced with grand limestone, brick, and stone structures. Some of those buildings housed a new kind of manufactory called a mill, which produced various goods. Bethlehem’s government even commissioned the creation of the first pumped municipal waterworks on the continent.

The Moravians remained pacifists during the Revolutionary War, although they geared up their factories and shops to produce resources for the war effort. They also sponsored a Continental Army Hospital at the Brethren House, where several hundred American soldiers convalesced. The Marquis de Lafayette was one of those many individuals, as he had rested in the hospital after receiving a wound at the Battle of Brandywine. Ultimately, some 500 servicemen died in Bethlehem, and their bodies were laid to rest on a hillside along First Avenue. British prisoners were billeted throughout the town as well, essentially transforming Bethlehem into a makeshift prison camp. And several members of the Continental Congress—including Benjamin Franklin and John Hancock—fled to Bethlehem when the British finally captured Philadelphia in 1777. The community fortunately transitioned well after the conflict and continued its emergence as a regional manufacturing center. People outside of the Moravian Church began buying land, denoting a shift away from the community’s earlier religious roots. (Only the church and its members were allowed to own property in Bethlehem prior to 19th century.)

The local development of canals—and later railroads—greatly transformed Bethlehem, too, for they allowed businesspeople to create more valuable goods like cigars, silk, and even refined zinc. But the greatest industrial operation in the area was the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, which grew to become the second largest producer of all steel products in the United States. Opened in 1857, the company established itself early as a significant supplier of steel goods that ranged from train track rails to military-grade ordinance. The Bethlehem Steel Corporation underwent a true metamorphosis though, when Charles M. Schwab acquired the rights to the factory in 1908. He revolutionized the business by creating the first steel I-beams at the plant, enabling architects and engineers throughout the world to construct skyscrapers for the first time. The Bethlehem Steel Corporation also became the largest shipbuilder on the planet during both World Wars, building more than 1,100 vessels in the Second World War alone. Today, Bethlehem is among the best places to vacation in the Keystone State. Its stunning scenery and cultural attractions are certain to provide for hours of entertainment.

-

About the Architecture +

Charles M. Schwab originally constructed the beautiful Historic Hotel Bethlehem at the start of the Roaring Twenties. He desired to operate an upscale hotel that could impress the influential business figures who regularly made trips to the Bethlehem Steel Corporation. In essence, Schwab hoped that the building would be the crown jewel of the community. He subsequently raised $1 million dollars to finance the project, which would have cost an estimated $15 million today! Construction began in earnest in 1921, with crews working tirelessly to create Schwab’s masterpiece. Many brilliant amenities appeared inside the hotel, including a barbershop, a shoeshine, and a “club room.” And as for the architecture, Schwab envisioned it displaying the finest aspects of Beaux-Arts-style architecture. Incredibly popular at the dawn of the 20th century, Beaux-Arts architecture has an extensive history in the Western world. This beautiful architectural form originally began at an art school in Paris known as the École des Beaux-Arts during the 1830s. There was much resistance to the Neoclassism of the day among French artists, who yearned for the intellectual freedom to pursue less rigid design aesthetics. Four instructors in particular were responsible for establishing the movement: Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste, and Léon Vaudoyer. The training that these instructors created involved fusing architectural elements from several earlier styles, including Imperial Roman, Italian Renaissance, ad Baroque. As such, a typical building created with Beaux-Arts-inspired designs would feature a rusticated first story, followed by several more simplistic ones. A flat roof would then top the structure. Symmetry became the defining character, with every building’s layout featuring such elements like balustrades, pilasters, and cartouches. Sculptures and other carvings were commonplace throughout the design, too. Beaux-Arts only found a receptive audience in France and the United States though, as most other Western architects at the time gravitated toward British design principles.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Charles M. Schwab, famous President of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation.

Thomas Edison, inventor known for such inventions as the motion picture camera and the lightbulb.

Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company and creator of the historic Model T.

Amelia Earhart, pioneering aviator who was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

Ozzie Nelson, musician and band leader who co-founded the program, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.

Harriet Hilliard, singer and actress who co-founded the program, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.

Phyllis Diller, legendary comedian whose career spanned some five decades.

Tony Bennett, musician known for such hits as “Because of You,” “Rags to Riches,” and “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.”

Shirley Temple, child actress known for her role in Bright Eyes and The Little Princess.

Bob Hope, comedian and patron of the United Service Organization (USO).

Muhammad Ali, professional boxer and political activist regarded as one of the greatest athletes of the 20th century.

Jack Nicklaus, winner of 18 major golf championships—the most of any professional golfer.

Chi-Chi Rodríguez, winner of 22 PGA Tour Championships, which ranks seventh all time.

Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama.

Jessie Jackson, Baptist minister and civil rights activist.

Henry Kissinger, 56th U.S. Secretary of State (1973 – 1977)

Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1940 – 1945; 1951 – 1955)

Dwight D. Eisenhower, 34th President of the United States (1953 – 1961), and Supreme Allied Commander Europe during World War II.

John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (1961 – 1963)

Gerald Ford, 38th President of the United States (1974 – 1977)

Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States (1993 – 2001)

-

Women in History +

Amelia Earhart: Amelia Earhart was one of the first celebrity guests to arrive at the Historic Hotel Bethlehem, arriving by plane to attend a banquet held in her honor in 1928. In fact, she had flown herself down from Rochester, New York, on a three-hour trip. Amelia Earhart was a legendary aviator who bore the distinction of being the first female to pilot a flight across the Atlantic. Climbing aboard a Fokker Trimotor dubbed “Friendship,” Earhart and her copilot, Wilmer Stultz, began the historic trip from an airfield in Newfoundland in June of 1928. In just under a single day, Earhart and Stultz landed at Pwll in South Wales. She became an overnight international celebrity for her achievement. When Earhart returned to the United States, she was given a massive ticker-tape parade along the Canyon of Heroes in New York City. President Calvin Coolidge even held a reception in her honor at the White House shortly thereafter. Earhart then followed up her grand achievement five years later, when she completed a transatlantic solo flight from Canada to Northern Ireland. Becoming the first woman to finish such a trip alone, Congress bestowed Earhart with the Distinguished Flying Cross. Her fame only continued to grow, as tales of her accomplishments captivated countless Americans. Earhart’s celebrity status even caused her to development a close friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt during the mid-1930s. When she was not busy flying, Earhart served as visiting faculty member in aeronautical engineering at Purdue University, and vigorously supported the causes championed by the National Women’s Party. Earhart also founded the Ninety-Nines, an all-female international organization that supports the professional growth of female pilots. Yet, her career was tragically cut short in 1937, when she disappeared while attempting a circumnavigational trek across the globe.