Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

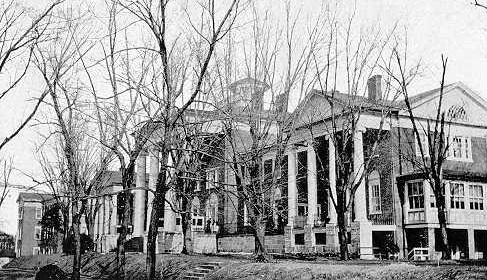

Discover Blackburn Inn, which was the Western State Hospital and renovated by architect Thomas R. Blackburn, a protégé of Thomas Jefferson.

The origins of Blackburn Inn date back to 1828, when the Virginia state government first created the 80-acre Western State Hospital. Within a matter of years, the site became one of Virginia’s busiest hospitals. The man largely responsible for this development was Doctor Frances T. Stribling, the facility’s superintendent. Dr. Stribling was prominent in many of the nation’s leading medical circles, having helped found the forerunner to the American Psychiatric Association. He was also a proponent of what he called “moral treatment,” in which doctors emphasized the emotional well-being of their patients. As such, his decision to expand the complex reflected his desire to provide the best care possible. Dr. Stribling hired architect Thomas R. Blackburn to head the renovation project in the mid-1830s. Blackburn was a respected protégé of former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, who himself was a noteworthy architect. Together, Stribling and Blackburn directed the magnificent renovation of the complex, which saw the addition of spacious room wings, verdant gardens, and a magnificent cupola on top of the main hospital building. When construction concluded in 1836, the Western State Hospital stood as an architectural masterpiece. Under Dr. Stribling’s leadership, the facility provided some of the most superlative mental healthcare in the whole United States. But the hospital closed a century later and reopened as a medium-security prison. Then in the early 2000s, Virginia politicians decided to shut down the jail. The complex sat dormant until real estate developers fortunately purchased the site in 2006. After undergoing a long renovation, the extensive overhaul was completed in 2018. By the summer of that year, several of the complex’s buildings were transformed into a wonderful boutique hotel called the “Blackburn Inn & Conference Center.” The hotel merged modern and historic expressions with elegant touches including vaulted ceilings, intricate molding, and light-filled hallways. A member of Historic Hotels of America since then, the Blackburn Inn continues to inspire every guest who steps inside.

-

About the Location +

Located deep within the Shenandoah Valley, Staunton, Virginia, is a historic city with a past dating back centuries. This quaint bucolic community was specifically founded in the 1740s, although the first settlers arrived in the area a decade earlier. Interestingly, the person responsible for laying out its first street grid, Thomas Lewis, was actually the son of the very first settler, John Lewis. Various historical accounts attest that the senior Lewis was a European immigrant who had originally escaped the continent in search of religious tolerance. Finding costal Pennsylvania to be overcrowded, Lewis transported his family to the remote Virginia frontier. Dozens of other Protestant migrants settled the region over the next few years, especially once William Beverley—a wealthy English planter and local landowner—began selling parcels of land surrounding the Lewis farm. Over time, a sizeable number of the residents began forming the nucleus of a town, which Thomas Lewis took a leading role to create. Calling the town “Beverly’s Mill Place,” the residents eventually renamed it “Staunton” after the wife of Virginia’s then-Lieutenant Governor, Lady Rebecca Staunton.

Staunton grew exponentially over the following decades, emerging as arguably the most important community in colonial western Virginia. In fact, the town’s status made the royal government establish it as both the capital for Augusta County, as well as for the entire western frontier. Some of Virginia’s patriot leadership—including Thomas Jefferson—even briefly met in Staunton during the American Revolution after they were chased out of both Richmond and Charlottesville. (Jefferson also spent time in Staunton practicing as a lawyer throughout the 1760s and 1770s.) Driving Staunton’s social and political changes was its proximity to several main thoroughfares, specifically the historic “Great Wagon Road.” Later renamed as the “Valley Pike,” it connected the Virginian “backcountry” with its wealthy Tidewater region. Many settlers from all across the Atlantic world pushed further inland from Staunton along this route, a practice that remained strong well into the 19th century. Among the people to settle in Staunton at the time included the parents of future U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, who arrived in the city as Presbyterian missionaries.

The town also evolved rapidly into a regional economic center, due to the many transient merchants who transported large amounts of grain and tobacco through Staunton. This prosperity continued for generations, particularly after the Virginia Central Railroad began supplementing commercial traffic into Staunton alongside the Valley Pike during the 1850s. The combination of the railroads and improved roadways made it possible for local businesspeople to ferry their goods to markets farther away, sparking a minor wave of industrial construction that lasted for decades. Several factories subsequently opened as such, creating a variety of products that ranged from textiles to wagons parts. But Staunton’s economic affluence eventually made it an important military target once the American Civil War sundered the nation. While Staunton saw little action amid the first few years of the war, it increasingly became a focal point for Union and Confederate armies toward the latter half of the conflict. The climax of the Civil War for Staunton came in June of 1864, when Union General David Hunter occupied the city with 10,000 soldiers following the Battle of Piedmont. Only staying for two days, General Hunter’s army destroyed the local railroad station, as well as numerous warehouses, factories, and mills.

Staunton has since remained one of the Shenandoah Valley’s most celebrated communities, fueled by a thriving cultural heritage tourism industry. The community itself is home to a number of fascinating attractions, including The Camera Heritage Museum, the Frontier Culture Museum, Mary Baldwin University, and the Wharf Area Historic District. Perhaps the greatest destination within the city limits is the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library, which is housed within the former president’s childhood home. Additional presidential sites are located just a few miles outside Staunton, too, including Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and James Madison’s Montpelier. Furthermore, travelers interested in Virginia’s rich Civil War heritage will find Staunton an attractive place to visit, for it is close to the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Other nearby destinations include the greater Shenandoah Valley National Park, the Luray Caverns, and the Cyrus McCormick Farm. Come experience a true cultural experience by visiting historic Staunton today!

-

About the Architecture +

The Blackburn Inn & Conference Center stands today as a brilliant example of Greek Revival architecture, one of the most common historical styles in the southern United States. Greek Revival style architecture first appeared throughout the western world during the late 18th and early 19th century. It appeared at a time when intellectuals in both Europe and English-speaking North America became obsessed with Greco-Roman culture. The style borrowed heavily from elements of Greek architecture, using it to build a wide variety of civic facilities. Ancient Greek culture was especially popular, for most people knew little about its history. The first archeological excavations had occurred earlier in the 18th century, exposing Hellenistic Greece to the West en mass for the first time. But while many European architects utilized the Greek Revival-style architecture, it truly reached the pinnacle of its popularity in the United States. In fact, some historians consider Greek Revival-style to be the nation’s very first “national” architectural form! The reason for that steeped interest was drawn from romanticized interpretations of Greek society that had started to permeate throughout America. The United States was a young nation at the end of the 1700s, and its citizens were desperate for previous democratic examples that they could emulate in their won republic. Nowhere was this desire more apparent than among the country’s founding elite. They looked to the philosophies of the Grecian republics of antiquity for successful examples of popular government. This pursuit gradually seeped into the cultural fabric of the United States, influencing everything from artwork to literature. Even the names of several towns—including Ithaca, New York, and Athens, Georgia—reflected this development.

The national fascination with ancient Greece took root in America’s architectural practices, too. Many architects began designing buildings that mimicked structures like the great the Parthenon. Even Thomas Jefferson—known to be an accomplished engineer—used Greek design principles to create the Virginia State Capitol Building in 1785. American architects—as well as their European counterparts—typically constructed buildings in the style of Greek Revival by using a symmetrical foundation anchored by combination of stucco and wooden walls. They subsequently painted them white to give the illusion that they had been constructed out of marble or some other elegant stone. A brilliant front portico acted as the main entrance into the building, which was surrounded by a large porch that could span the length of the building’s front façade. The roof itself was low pitched and was either gabled or hipped. Just below the rooftop rested an area called the “entablature” that consisted of elaborate trimming and cornicing. In some cases, the entablature itself consisted of a frieze where most of the decorative work resided. But perhaps the single greatest defining feature of Greek Revival-style buildings were the many columns (or pilasters) that proliferated throughout the interior and exterior. Architects designed the columns in one of three sub-categorical styles known as Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. They were also usually fluted or smooth and featured an ornate structure called a “capital” at the top. By the 1820s, Greek Revival-style architecture had become the most widely used in the United States. It remained that way for the next three decades, until different revivalist architectural forms finally displaced it in popularity.