Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

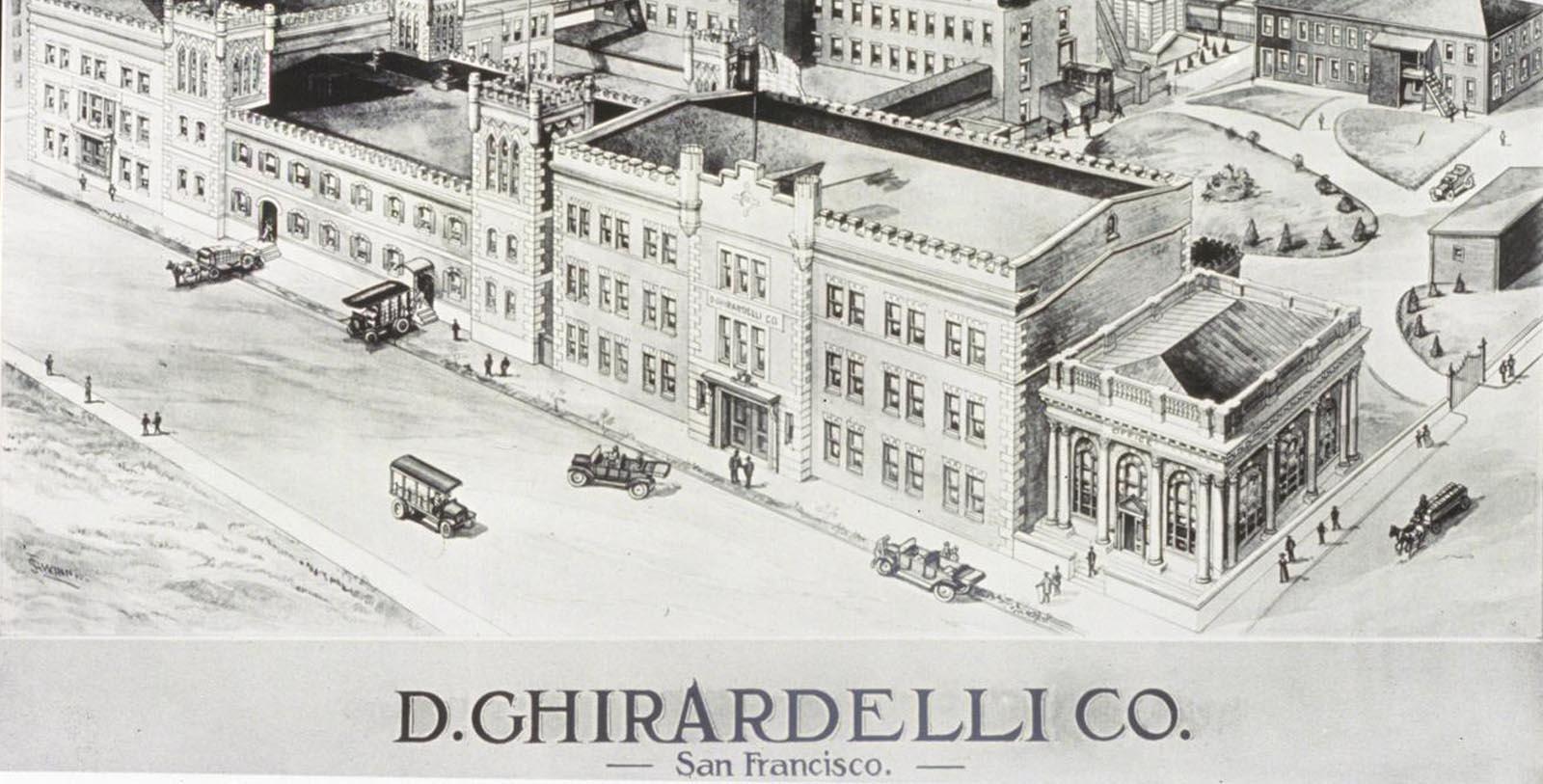

Discover Fairmont Heritage Place, Ghirardelli Square, which is located in the original Ghirardelli Chocolate Company of San Francisco.

Fairmont Heritage Place, Ghirardelli Square, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2016, dates back to 1893.

VIEW TIMELINEFrom the time he was a young boy, Domenico Ghirardelli had long been fascinated about the international confectionary trade. A native of Rapallo, Italy, Ghirardelli had pursued a career in the field from the time he was an adolescent. During his youth, he had begun to apprentice under a local candy maker in his home town that would expose him to the world of chocolate. Upon completing his education, Ghirardelli and his wife decided to find new markets to explore the confectionary business and immigrated to South America to setup a “coffee and chocolate establishment.” In 1838, the two endured a harrowing trip, traversing Cape Horn for their final destination—Lima, Peru. Ghirardelli proceed to manage their nascent business for the better part of a decade, operating a small candy store next to a carpentry shop owned by an American named James Lick. The two became close friends. Eventually, Lick decided to return back the United States roughly a decade later in 1847, specifically settling in San Francisco. While Ghirardelli continued to work at his quaint storefront under the name “Domingo,” Lick began selling nearly 600 pounds of his chocolate throughout California.

Soon enough, Lick informed Ghirardelli of the gold rush unfolding in California and opted to follow his friend to America’s Pacific Coast. Immigrating to Stockton, Ghirardelli and his family created a general store to service the area’s mining community. Ghirardelli himself entertained the dream of working as a prospector in the Jamestown-Sonora area. The family’s business was far more rustic than their business in Lima, as it primarily consisted of a massive tent located just beyond the city limits. Still, business proved to be lucrative. Inspired, Ghirardelli created a second, much larger shop at the corner of Broadway and Battery in downtown San Francisco. Originally named “Ghirardely & Girard,” it would soon grow into an exclusive chocolate shop known as the “Ghirardelli Chocolate Company” a few months later. But in 1851, a series of tragic fires destroyed the store, as well as nearly 1,500 buildings in the surrounding neighborhoods. Undeterred, Ghirardelli reopened his confectionary at a number of locations before finally leasing an entire city block known as the Pioneer Woolen Mill.

The financial success of the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company grew exponentially throughout the latter-half of the 19th century. It proved so great that the Ghirardellis were able to purchase the entire Pioneer Woolen Mill complex for the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company. Around this time, the Ghirardellis commissioned architect William S. Mooser to renovate the space, so that it could better house their company’s industrial machinery. Three of his sons soon became partners in the company and eventually assumed complete control upon their father’s death in 1894. The company grew into a major global manufacturer of chocolate goods under their watch, distributing their products to such countries like China, Japan, and Mexico. By the middle of the 20th century, the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company had become one of the largest confectionaries in the world. Yet, in the early 1960s, the business moved their production facilities to San Leandro, California, leaving a single store called the “Manufactory” in its wake. The rest of the block was left abandoned. Fortunately, William M. Roth and his mother, Lurline Matson Roth, purchased most of the vacated spaces in order to save them from the wrecking ball. The Roths then hired the architectural firm Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons—as well as landscape architect Lawrence Halprin—to convert the location into a commercial facility known as “Ghirardelli Square.”

But the Roths took great pains to preserve much of the complex’s historical architecture, go so far as to use the original brick to reconstruct several units. Over time, a variety of restaurants and boutique shops inhabited Ghirardelli Square. Then, in 2008, those businesses were joined by a brand new five-star hotel called the “Fairmont Heritage Place, Ghirardelli Square.” Ghirardelli Square has since become one of San Francisco’s most cherished attractions, charming thousands of visitors every year. Among the most celebrated cultural attractions onsite is the Fairmont Heritage Place, Ghirardelli Square, which has built a strong reputation for its unrivaled hospitality and cutting-edge amenities. This historic residence-style hotel offers guests today the opportunity to experience the rich heritage of both Ghirardelli Square and San Francisco as a whole.

-

About the Location +

Fairmont Ghirardelli Square resides within Fisherman’s Wharf, one of San Francisco’s most revered neighborhoods. It draws its name from the wealth of fishing trollies that once inhabited the region in great numbers at in the latter-half of the 19th century. Italian immigrants operated the fleet of green, lateen-rigged sailboats that filled the area, with many bearing the name of Saint Peter—the Patron Saint of Fishermen. Passengers on nearby steamers recalled hearing melodic renditions of the song “Verdi” emanating from the fishing vessels as they passed, which acted as a form of communication among the ships in the area’s normally dense fog. The work was tough and not particularly financially rewarding, since most fishermen made only two to three dollars a week. But they provided a source of pride, nonetheless, as it took great skill to navigate the rough waters throughout the San Francisco Bay. The sailboats gradually disappeared in favor of more technologically advanced gas-powered boats as the Gilded Age reached its zenith. Known as “Monterey Hull” ships, their small, noisy engines provided a new iconic sound that came to characterize Fisherman’s Wharf. The introduction of the new boats enabled the fishermen—now in their second generation—to work out on the water for much longer periods of time. It also gave their vessels more strength to carry back unprecedented amounts of freshly caught wildlife.

As petroleum-fueled machines and large dockyards appeared in Fisherman’s Wharf, dozens of warehouses and seafood markets emerged along the streets directly behind them. The economic proliferation that defined late 19th-century San Francisco had reached the area, leading to its rapid urbanization. But the dramatic San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 greatly affected the area, just like the rest of the city. As such, Fisherman’s Wharf underwent another period of development in the years leading up to World War I. Much of the reconstruction projects were driven by the Panama—Pacific International Exposition, which had selected the neighborhood to host the site of its 1915 annual conference. The land was subsequently sold to private developers once the exposition ended, who set about creating a series of brand new residential and commercial structures. Further expansions to the area occurred in the 1930s, following the completion of the iconic Golden Gate Bridge. Civic leaders specifically widened Lombard Street in order to accommodate the traffic coming from the bridge. The heavy travel along the road soon lead to its transformation into a strip of roadside motels. Those businesses acted as the catalyst that turned Fisherman’s Wharf into one of the city’s main cultural attractions. Nonetheless, Fisherman’s Wharf maintains a high number of its historic structures from the early 20th century, giving it a historic character unlike many of San Francisco’s many other neighborhoods.

-

About the Architecture +

Listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, Ghirardelli Square is a massive, historic commercial complex just moments away from Fisherman’s Wharf. The first buildings to inhabit the space was an industrial building known as the Pioneer Woolen Mills, which debuted for the first time in 1858. Operated by a company of merchants, Heynemann, Pick and Company, the complex was a wooden structure that housed the very first woolen mill on the entire West Coast. Not only that, but the Pioneer Woolen Mills were also one of the first factories founded in all of California. The mill itself produced the local coarse-woven goods, creating a lucrative business model that saw wool products made cheap and efficiently. The business was incredibly active, operating with 16 looms powered by a coal-fired steam engine. But when the structure burned down in 1861, it was replaced by Swiss-born architect William S. Mooser. The new mill structure stood four-stories tall and extended for some 150 feet. Its layout was rather simplistic, with nor dramatic ornamentations save for the cornice line along the rooftop. Mooser specifically developed its entire faced with locally manufactured red brick that was laid in American bond. Business only continued to grow. It became so prosperous that the mill had expanded to own some 130 looms by the beginning of the 1880s. But a dramatic drop in business resulted in the mill shuttering its doors completely in 1889.

Eventually, the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company purchased the Pioneer Woolen Mills in 1892. The company had leased a portion of the building a decade prior for the purpose of housing its corporate offices. Over time, though, the Ghirardellis moved portions of its manufacturing operations into the facility, although they quickly ran out of space. As such, the Ghirardelli family decided to completely overhaul the complex so that it was better suited for industrial production. They quickly started acquiring all the other neighboring structures on the block, with the hope of melding them together to for a massive new factory complex. For the project, they hired local architect William S. Mooser, Jr., who was the son of the same architect who reconstructed the Pioneer Woolen Mills some 30 years ago. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, “the complex achieved architectural distinction and became a mode of factory design.” The Ghirardelli Chocolate Company would occupy the space until the middle of the 20th century, when it vacated the premises for a more modern plant in San Leandro. William M. Roth worked with his mother, Lurline Matson Roth, to save the structure upon its abandonment The Roths hired the architectural firm Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons—as well as landscape architect Lawrence Halprin—to convert the location into a commercial facility known as “Ghirardelli Square.” The U.S. Department of the Interior has even identified their work on the facility as a “prototype of commercial adaptive re-use.” The destination has since attracted dozens of new businesses ever since, including the magnificent Fairmont Heritage Place, Ghirardelli Square, in 2008.

The specific architecture that currently defines the hotel’s portion of Ghirardelli Square can best be described as “Modernist.” Modernist architecture—otherwise known as “modernism”—originally emerged in the early 20th century as a response to the continued industrialization of Western society in the abstract. Perhaps some of the best known architects to establish this line of thought were Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The philosophical design principle embraced the ideals of function, simplicity, and rationality, as a way to reject the previous traditional aesthetics of the Victorian Age. But architects also believed that the ostentatious architectural forms of the century prior had failed to address rising social concerns born of industrialization, and desired to create simplistic, yet sleek, structures that conveyed a sense of communal purpose. As such, Modernist architecture specifically called for the elimination of ornamentation from the exterior of a building’s outward appearance, instead adopting a steel frame lined with large windows and open entryways. Building materials such as concrete and metal became commonplace, for they represented the idea of modern technological progress. Furthermore, Modernist architects made explicit use of vertical lines and rectangular shapes to showcase a sense of symmetry. Inside, Modernist buildings featured wide, open spaces filled with natural light that represented practicality and comfort. And despite its early origins, Modernism continues to be among the most extensively used architectural styles today.