Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover The Seelbach Hilton Louisville, which has long been inspiration for historical icons, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, who used the hotel as inspiration for his brilliant 1925 novel, The Great Gatsby.

The Seelbach Hilton Louisville, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2015, dates back to 1905.

VIEW TIMELINE

Welcome to The Seelbach Hilton Louisville

Meet Larry Johnson, the resident historian of The Seelbach Hilton Louisville. For more videos about The Seelbach Hilton Louisville’s history, please see the hotel’s media gallery further along its profile!

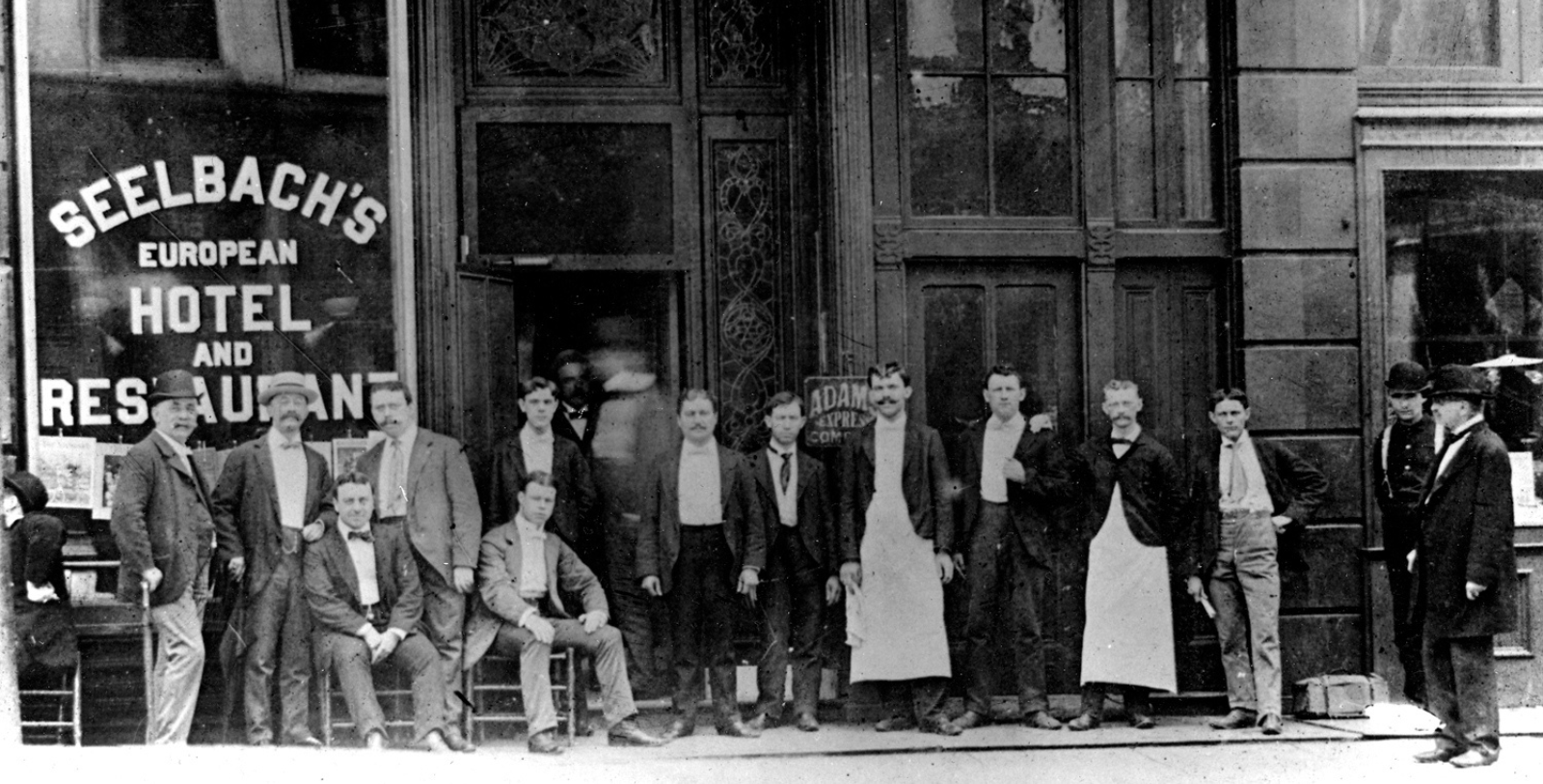

WATCH NOWListed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places by the U.S. Department of the Interior, The Seelbach Hilton Louisville has stood as one of Kentucky’s most cherished landmarks for more than a century. Founded in the early 1900s, this magnificent historic hotel was actually the lifelong dream of two brothers named Louis and Otto Seelbach. Hailing from Bavaria, the brothers had originally moved to Louisville to learn more about the American hospitality industry. They thus pursued a number of different economic opportunities as a way to further educate themselves. After spending several years running various restaurants and clubs, the brothers eventually began constructing their own hotel at the corner of 4th and Walnut Street. The new, ornate “Seelbach Hotel” finally experienced its much-anticipated debut in 1905, drawing 25,000 visitors to its five-hour grand opening event. Designed by W.J. Dodd and F.M. Andrews, the hotel displayed a lavish, turn-of-the-century Beaux-Arts architectural style that embodied the “Old World” opulence of Parisian hotels. Gorgeous imported European marble proliferated throughout the lobby, as did beautiful Renaissance-inspired carvings made out of mahogany and bronze. The architects mounted a vaulted dome of 800 glass panels atop the lobby, too, making it one of the hotel’s defining traits. Conrad Arthur Thomas—the most famous painter of Native American culture in the world—even decorated the space with huge murals that depicted pioneer scenes from Kentucky’s history. The Seelbach Hotel’s luxurious characteristics quickly earned it a considerable reputation as such, which allured countless guests from across the nation.

The hotel’s stunning success was the result of the masterful guidance that Louis and Otto Seelbach had provided, who remained its dedicated stewards for a long time. However, Louis Seelbach died in 1925 and Otto passed away some eight years later. The Seelbach Hotel Company disbanded shortly thereafter, with their descendants putting the building up for sale. Despite the absence of the Seelbach brothers, the Seelbach Hotel nonetheless remained an important cultural icon in Louisville for decades. But in 1968, a severe loss in revenue forced the Seelbach Hotel to close for good. Facing an uncertain future, salvation fortunately arrived when new owners H.G. Whittenberg, Jr. and Roger Davis began a series of comprehensive renovations in partnership with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Costing more than $28 million to complete, the revitalized Seelbach Hotel reopened to great renown during the early 1980s. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company gained control over the hotel afterward, buying out both Whittenberg and Davis. A subsidiary of Radisson Hotels called the “National Hotels Corporation” then managed the Seelbach Hotel until Medallion Hotels, Inc., purchased the building in 1990. It quickly made several fantastic architectural updates, including the installation of an 18,500-square-foot conference center. Additional renovations transpired under the watch of Meristar Hotels and Resorts, which bought the Seelbach Hotel in 1998. Another round of expansive construction projects continued several years later in 2007, once Investcorp International became the new owner. Like its predecessors, both institutions had invested heavily to ensure that the hotel’s architectural integrity remained intact.

Now known as “The Seelbach Hilton Louisville,” this fantastic historic hotel continues to possess a prestigious reputation for its exceptional service and heritage. Indeed, the names of numerous celebrities still populate the guest registry to this very day. Among the most noteworthy names are those of U.S. Presidents, such as William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton. Situated in the center of bourbon and whiskey country, the hotel also attracted infamous underworld kingpins and gangsters during Prohibition. Notorious criminal figures included Lucky Luciano, "Beer Baron of the Bronx" Dutch Schultz, and the most legendary outlaw at the time, Al Capone. A frequent guest of the building, Capone often dined in “The Oakroom,” where he would play cards in a small alcove within the venue. The gangster’s affinity for the facility specifically stemmed from its two hidden doors, which led directly into secret passageways. (The Oakroom still displays the large mirror Capone had sent down from Chicago, so that he could always be aware of any approaching intruders.) Cincinnati-based mobster and "King of the Bootleggers" George Remus also spent time at the hotel, where he became friends with writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald himself had visited the hotel while training for the U.S. Army at nearby Camp Taylor, and eventually used it to help write his famous novel, The Great Gatsby. In fact, the hotel’s Grand Ballroom was the inspiration for the wedding scene that took place between two of the book’s main characters, Tom and Daisy Buchanan! (Interestingly, Fitzgerald conceptualized the character of Jay Gatsby based on his interactions with Remus.)

-

About the Location +

The Seelbach Hilton Louisville resides just moments away from the West Main Street Historic District, which is one of the most celebrated neighborhoods in downtown Louisville, Kentucky. While the area is now known for its fantastic array of cultural attractions, it first started out as the site for a rudimentary wilderness citadel back during the late 18th century. In 1778, a group of settlers led by Lieutenant Colonel George Rogers Clark arrived in the vicinity, who had been dispatched to attack a British outpost several miles away. Establishing a settlement on nearby Corn Island, the pioneers remained in the area for months thereafter while Clark pushed forward toward his objective. The settlers eventually created a wooden stockade called “Fort Nelson” some four years later, with Richard Chenworth presiding over the small community that emerged around it. Then, in 1784, the Virginia General Assembly (Kentucky was then still a part of Virginia) formally approved an official town charter recognizing the village as the community of “Louisville.” The locals had selected the name in honor of King Louis XVI, who had just helped the newly created United States defeat Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. Louisville quickly became a point of embarkation for additional generations of frontiersmen eager to head west, with the most notable being Meriweather Lewis and William Clark of the famed Lewis and Clark Expedition. But Louisville’s proximity along the banks of the Ohio River also made it a significant trade center. Hundreds of merchants opened their owns storefronts and warehouses around old Fort Nelson, which sold products like whiskey and tobacco. Soon enough, Louisville was one of the most visited ports along the entire Ohio River, attracting all kinds of businesspeople from both the North and South. (Railroads also enhanced Louisville’s economic standing, starting with the arrival of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad in the mid-1850s.)

Louisville’s prominence as a commercial hub made it extremely important to the Union war effort during the American Civil War. Even though Kentucky as a whole was a slave state, it officially remained loyal to the nation due to its economic ties with the northern states of the Old Northwest. Fortunately, the city escaped suffering any damage amid the conflict, although several nearby communities—including Perryville and Corydon—experienced heavy fighting at one point or another. (The Battle of Perryville in 1862 was one of the war’s most strategically significant fights, as it prevented a large Confederate army from occupying the commonwealth and threatening the Midwest.) Louisville once again proceeded to grow rapidly as a regional economic powerhouse as soon as the hostilities ended, with a spate of new commercial edifices debuting downtown. Main Street in particular became a major site for the construction work that characterized Louisville’s growth at the century’s end. The designs of the buildings were far more intricate, showcasing the beauty of Romanesque and Mediterranean-inspired architecture. Most of the structures even possessed their own unique detailing, including a rare array of cast iron facades. The area remained the heart of Louisville’s vibrant economy throughout much of the 20th century, until newer industries overtook the local economy in importance. Today, most of the historic warehouses and storefronts have been thoroughly renovated, reopening as boutique shops, restaurants, and art galleries. In fact, the West Main Street Historic District is also known locally as “Museum Row,” due to the high number of museums that reside in the neighborhood. Among those cultural institutions active now are the Muhammad Ali Center, the Louisville Slugger Museum, the Frazier History Museum, and the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft. Additional attractions are nearby, too, with the most notable being the legendary Churchill Downs racetrack.

-

About the Architecture +

The Seelbach Hilton Louisville still displays the same turn-of-the-century, Beaux-Arts architectural style that architects W.J. Dodd and F.M. Andrews originally created for it decades ago. Just as grand as the finest European hotels of the era, the building’s interiors featured a lobby furnished with marble from Italy and Switzerland. Furthermore, the space contained numerous mahogany and bronze fixtures that conveyed a Renaissance-inspired eclectic. The architects also mounted a vaulted dome of 800 glass panes atop the space, which many contemporaries considered to be an engineering marvel. Arthur Thomas—the most famous painter of Native American culture at the time—even decorated the lobby with huge mural paintings of pioneer scenes from Kentucky’s history. Dodd and Andrews specifically relied upon Beaux-Arts-inspired architecture as the main influence behind their work. Widely popular around the dawn of the 20th century, this beautiful architectural form originally began at an art school in Paris known as the École des Beaux-Arts during the 1830s. There was much resistance to the Neoclassism of the day among French artists, who yearned for the intellectual freedom to pursue less rigid design aesthetics.

Four instructors in particular were responsible for establishing the movement: Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste, and Léon Vaudoyer. The training that these instructors created involved fusing architectural elements from several earlier styles, including Imperial Roman, Italian Renaissance, and Baroque. As such, a typical building created with Beaux-Arts-inspired designs would feature a rusticated first story, followed by several more simplistic ones. A flat roof would then top the structure. Symmetry became the defining character, with every building’s layout featuring such elements like balustrades, pilasters, and cartouches. Sculptures and other carvings were commonplace throughout the design, too. Beaux-Arts only found a receptive audience in just a few countries though, as most Western architects gravitated toward British design principles. That being said, Beaux-Arts was received incredibly well throughout the United States, emerging as one of its most enduring architectural forms. Indeed, many Beaux-Arts-designed structures still survive in America today, with some even bearing a listing in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

This architectural distinctiveness has also manifested within many particular spaces on-site, with the most notable area being The Oakroom. The Oakroom’s transformation from a gentlemen’s billiard hall to a refined dining space is a fascinating tale of evolution, both architectural and cultural. Originally conceived in 1907 as an exclusive retreat for men, the room’s design embodied the era’s social norms, with its hand-carved American Oak paneling, private bar, and card room providing a secluded space for relaxation and leisure. The exclusion of women from such spaces reflects a time when societal roles were rigidly defined, and the very presence of billiard tables in this setting symbolized a form of masculinity associated with wealth, status, and leisure.Even though the room has since been restored to its present elegance, elements of its past remain visible. The oak-paneled walls and columns still retain their stately presence, while the subtle traces of the former billiard room—such as remnants of the cue racks on the south wall—invite guests to imagine a bygone era of gentlemanly games and private indulgence. The Oakroom’s hidden features, like the secret exit once used by notorious figures such as Al Capone, add an air of mystery and intrigue to the space. The “Al Capone room,” as it is now known, harkens back to the Prohibition days when organized crime and covert activities were part of the cultural fabric. The boarded-up panel on the southwest wall, which once allowed swift escapes for gangsters, adds an almost cinematic quality to the room’s history, reminding guests that the Oakroom was not just a place of leisure, but also one of shadowy dealings and escape.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Elvis Presley, singer, musician and actor, affectionately known as the “King of Rock.”

Julia Child, cooking teacher and television personality remembered for her show, The French Chef.

Lucky Luciano, founder of the Genovese crime family, as well as The Commission.

Al Capone, gangster infamously remembered as the head of the Chicago Outfit during Prohibition.

Dutch Schultz, gangster and bootlegger remembered as the "Beer Baron of the Bronx."

F. Scott Fitzgerald, author remembered today for writing The Great Gatsby.

William Howard Taft, 27th President of the United States (1909 – 1913) and 10th Chief Justice of the United States (1921 – 1930)

Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States (1913 – 1921)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32nd President of the United States (1933 – 1945)

Harry S. Truman, 33rd President of the United States (1945 – 1953)

John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (1961 – 1963)

Lyndon B. Johnson, 36th President of the United States (1963 – 1969)

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States (1977 – 1981)

Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States (1993 – 2001)

George W. Bush, 43rd President of the United States (2001 – 2009)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

The Hustler (1961)

The Insider (1999)

The Great Gatsby (2013)